Essays and Book Reviews on Evolutionary Psychology, Anthropology, the Literature of Science and the Science of Literature

Ted McCormick on Steven Pinker and the Politics of Rationality

Reviewing Steven Pinker’s book Rationality for Slate, McCormick takes issue with a small handful of examples of irrationality because the perpetrators are on the left side of the political divide. He argues that Pinker’s true purpose is to promote his own political agenda. But McCormick’s examples have some issues of their own.

Concordia University historian Ted McCormick has serious reservations about Steven Pinker’s new book, Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems So Scarce, Why It Matters. His short review in Slate provides of long list of reasons why Pinker’s project was doomed from the outset. But the one issue that really seems to bother McCormick is that “instead of confronting his targets head on, the middle chapters engage in a kind of indirect culture warfare, dragging foes in as apparently incidental examples of irrationality or motivated reasoning.” You see, by McCormick’s lights, Rationality isn’t about rationality at all, but about scoring points against ideological rivals.

Throughout his review, McCormick is at pains to ward off the impression that he’s tilting at windmills. He admits “the bulk of the book is less an open culture war campaign than a May Day of rationality’s arsenal,” and he even goes so far as to call it “entertaining,” noting that if you skip the bad parts, “you can find an informative and briskly written book about types of reasoning and their applications.” In other words, the bulk of the book is entertaining and does exactly what Pinker says he wanted it to do. Still, McCormick makes it clear he isn’t giving Rationality his endorsement. “The trouble,” he writes, “begins when you read all the words,” by which he means read between the lines. Doing so, he seems convinced, will reveal that all this stuff about the methods of reasoning is little more than a smoke screen hiding Pinker’s real points, which are political.

This can be seen, McCormick insists, when you look at the examples of irrationality Pinker uses: “as the examples pile up, one wonders what is being defended.” McCormick is fine with all the examples of right wing or religious irrationality. “Where the shoe fits,” he writes, “fair enough.” But the small handful of examples from the left side of the political divide are another matter. Here’s an emblematic passage from the review:

Pinker lets his own solidarities and enmities shape his concern for facts and argumentation. This results in large, unsupported claims, as when a Politico op-ed he co-wrote in defence of Bret Stephens is his sole footnoted source for the claim that logical fallacies are “coin of the realm” across academia and journalism. It also produces some mystifying assertions, such as that the 2020 murder of George Floyd led to “the sudden adoption of a radical academic doctrine, Critical Race Theory”—and that both CRT and Black Lives Matter are driven by an exaggerated sense of Black people’s statistical risk of being killed by police. While Pinker soon walks back what he suggests may be a “psychologically obtuse” account of BLM’s origins, the chronological nonsense of the claim and the characterization of CRT as a “doctrine” stand without evidence or argument. After all, he might say, they’re just examples.

Unsupported claims and nonsense sound pretty bad. But, given all the examples McCormick fails to look up the citations for and doesn’t fault as insufficiently supported, examples in the realms of climate change, creationism, anti-vaxxism, Q-Anon and the like, you could be forgiven for wondering if he’s just mad Pinker is poking at some of his own pet causes.

Did Pinker really claim that fallacies are the coin of the realm “across academia and journalism” with reference to a single citation? You can find the passage on pages 92 and 93 of the hardback edition:

The ad hominem, genetic, and affective fallacies used to be treated as forehead-slapping blunders or dirty rotten tricks. Critical-thinking teachers and high school debate coaches would teach their students how to spot and refute them. Yet in one of the ironies of modern intellectual life, they are becoming the coin of the realm. In large swaths of academia and journalism the fallacies are applied with gusto, with ideas attacked or suppressed because their proponents, sometimes from centuries past, bear unpleasant odors and stains. [Here’s where the footnote appears referring to the article on Bret Stephens; it begins “For discussion of one example…”] It reflects a shift in one’s conception of the nature of beliefs: from ideas that may be true or false to expressions of a person’s moral and cultural identity. It also bespeaks a change in how scholars and critics conceive of their mission: from seeking knowledge to advancing social justice and other moral and political causes.

Pedantic of me to point out, I know, but McCormick’s “across academia and journalism” is a misrepresentation of Pinker’s phrase, “In large swaths of academia and journalism,” one that serves to increase the scope of a claim McCormick faults for being large and insufficiently supported. Still, the claim does require support, and it’s true that the footnote lists a single example.

The next question is what does the case of Bret Stephens reveal, if anything, about academia and journalism? The first point that jumps out is that the controversy surrounding Stephens involves The New York Times, the biggest name in journalism, and it began when critics faulted an article by Stephens for abhorrent arguments allegedly contained within it. The result was that the Times deleted large parts of the article. Since the Times is the source of record, you might assume the criticisms held some merit. Not so. The authors of the Politico article write,

the column incited a furious and ad hominem response. Detractors discovered that one of the authors of the paper Stephens had cited went on to express racist views, and falsely claimed that Stephens himself had advanced ideas that were “genetic” (he did not), “racist” (he made no remarks about any race) and “eugenicist” (alluding to the discredited political movement to improve the human species by selective breeding, which was not remotely related to anything Stephens wrote).

Those hyperlinks in the passage are to false charges leveled in the pages of The Guardian and Mother Jones, both newspapers with rather large circulations if my sources are correct.

So Pinker’s citation isn’t completely useless, but maybe it leaves something to be desired. It’s still just one case, and it doesn’t mention anything about academia. There is, however, another footnote at the end of the same paragraph. This one refers to a post by Jonathan Haidt arguing that universities must decide whether their main mission is to seek truth or to pursue social justice. Haidt writes,

As a social psychologist who studies morality, I have watched these two teloses come into conflict increasingly often during my 30 years in the academy. The conflicts seemed manageable in the 1990s. But the intensity of conflict has grown since then, at the same time as the political diversity of the professoriate was plummeting, and at the same time as American cross-partisan hostility was rising. I believe the conflict reached its boiling point in the fall of 2015 when student protesters at 80 universities demanded that their universities make much greater and more explicit commitments to social justice, often including mandatory courses and training for everyone in social justice perspectives and content.

Is 80 a significantly large number of universities to justify the phrase “large swaths”? Does demanding greater focus on social justice amount to succumbing to fallacies? Haidt’s position is in fact that campus activism is often motivated by faulty reasoning. The second part of the post Pinker cites lists some of these errors, including the conflation of correlation with causation. Haidt writes,

All social scientists know that correlation does not imply causation. But what if there is a correlation between a demographic category (e.g., race or gender) and a real world outcome (e.g., employment in tech companies, or on the faculty of STEM departments)? At SJU, they teach you to infer causality: systemic racism or sexism. I show an example in which this teaching leads to demonstrably erroneous conclusions [there’s an embedded video]. At Truth U, in contrast, they teach you that “disparate outcomes do not imply disparate treatment.” (Disparate outcomes are an invitation to look closely for disparate treatment, which is sometimes the cause of the disparity, sometimes not).

Of course, while these citations offer some support for Pinker’s claim, we can be sure McCormick isn’t convinced.

What about Pinker’s claims regarding Critical Race Theory and Black Lives Matter? First, the statistical matter: are CRT and BLM motivated by an overreaction to police shootings? McCormick doesn’t mention the numbers cited in the section he quotes: “A total of 65 unarmed Americans of all races are killed by the police in an average year,” Pinker writes on page 123, after making the claim McCormick objects to, “of which 23 are African American, which is around three tenths of one percent of the 7,500 African American homicide victims.” He cites the data on police shootings tracked by the Washington Post.* Pinker could have also cited a report by the Skeptics Research Center that shows Americans wildly overestimate the number of African Americans killed by police: “over half (53.5%) of those reporting ‘very liberal’ political views estimated that 1,000 or more unarmed Black men were killed, a likely error of at least an order of magnitude.” But his book isn’t about police shootings.

Next, can the claim that the murder of George Floyd led to widespread adoption of CRT be supported? A 2020 article in the BBC by Anthony Zurcher called Critical Race Theory: The Concept Dividing America includes this passage,

The term itself first began to gain prominence in the 1990s and early 2000s, as more scholars wrote and researched on the topic. Although the field of study traditionally has been the domain of graduate and legal study, it has served recently as a framework for academics trying to find ways of addressing racial inequities through the education system - particularly in light of last summer's Black Lives Matter protests. “The George Floyd murder caused this whole nation to take a look at race and racism, and I think there was a broad recognition that something was amiss,” says Marvin Lynn, a critical race theory scholar and professor of education at Portland State University.

What is it about Pinker’s chronology that strikes McCormick as nonsensical? He must understand that most people outside of academia only learned about CRT recently, and it’s been in the context of the newly heated discussion of racism instigated by Floyd’s killing. I suspect his issue is semantic—is it really CRT that’s being taught in schools?

The other semantic point here is whether Pinker should support his use of the term doctrine as applied to CRT; again, he goes so far as to call it a “radical academic doctrine.” I’m just going to refer to Richard Delgado’s definition from his 2012 textbook on the subject.

The critical race theory (CRT) movement is a collection of activists and scholars interested in studying and transforming the relationship among race, racism, and power. The movement considers many of the same issues that conventional civil rights and ethnic studies discourses take up, but places them in a broader perspective that includes economics, history, context, group- and self-interest, and even feelings and the unconscious. Unlike traditional civil rights, which stresses incrementalism and step-by-step progress, critical race theory questions the very foundations of the liberal order, including equality theory, legal reasoning, Enlightenment rationalism, and neutral principles of constitutional law.

Well, that sounds pretty radical to me. But does it amount to a doctrine? As far as I understand it, all CRT follows from the tenet that society is comprised of two groups, the oppressors and the oppressed, and the efforts of the oppressors to maintain their hegemony infect every institution imaginable, from universities, to courts, to scientific research programs. That’s why CRT “questions the very foundations of the liberal order.” That central division wasn’t discovered through any empirical methods; rather, it’s asserted as an axiom—or a doctrine. I have no doubt McCormick would call my take simplistic and naïve, but I’d counter that he’s using obfuscation to avoid legitimate criticism.

Let’s briefly consider another point McCormick takes issue with. This one includes the serious allegation that Pinker has misrepresented an activist’s writing.

Pinker treats Mariame Kaba’s 2020 New York Times op-ed in favor of police abolition as an example of confusing “less-than-perfect causation” with “no causation,” because it is based on the fact that, under the current system, few rapists are prosecuted. “The editorialist did not consider,” he writes, that fewer still might be prosecuted without the police. In fact, Kaba’s argument is not primarily based on rape at all; she begins by talking about how much time police spend on traffic violations and noise complaints, and proceeds through a century-plus history of failed attempts at police “reform” (the point of her piece). What good does such misrepresentation serve?

Pinker’s comments on the matter take up a whole three sentences on page 260, coming right after the example of people pointing to nonagenarian smokers as a refutation of the link between cigarettes and cancer. The idea is that people point to rare exceptions in their efforts to cast doubt on wider trends, and he does indeed suggest Kaba’s reason for wanting the police abolished is because “the current approach hasn’t ended” rape. But the quotation is accurate, and the failure of policing to end rape is part of her argument.

Is it really a misrepresentation to cite one part of her argument without mentioning the others? Possibly, but if so McCormick himself has a lot to answer for. What good does the alleged misrepresentation do? Well, it provides an illustrative example of people thinking an intervention that’s not a hundred percent effective can’t be effective at all—precisely the purpose Pinker wanted it to serve. What McCormick failed to notice is that Kaba makes the same error throughout her argument. She writes, for instance,

Minneapolis had instituted many of these “best practices” but failed to remove Derek Chauvin from the force despite 17 misconduct complaints over nearly two decades, culminating in the entire world watching as he knelt on George Floyd’s neck for almost nine minutes.

So, the reforms didn’t save George Floyd, but did they save anyone else? Kaba doesn’t think to ask. We should also ask if Kaba really believes police tactics haven’t improved at all since 1894, the date of her first example of a failed reform. Pinker, in the same footnote he uses to cite Kaba’s article, refers to a quantitative analysis of how policing affects crime that avoids the all-or-nothing fallacy he’s discussing in this section of his book. It paints a more optimistic, though by no means Panglossian, picture.

BLM, CRT, fallacies running rampant in journalism and higher education, police abolitionism—are you noticing a pattern? The only thing missing is cancel culture. By now, you won’t be surprised to find out McCormick faults Pinker for mentioning that topic as well (though not by name):

Blaming universities’ “suffocating leftwing monoculture” for popular mistrust of expertise, Pinker mentions two examples in the text: University of Southern California professor Greg Patton’s removal from a course after using the Chinese ne ga, which can sound like the N-word, and testimony from unnamed personal “correspondents.” (In a footnote, he invites readers to look to Heterodox Academy, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, and Quillette—all of it—for further examples.) The very next paragraph warns of “illusions instilled by sensationalist anecdote chasing.” Doctor, heal thyself!

If you’re following along, the offending section is on pages 313 and 314. What Pinker wrote is that “confidence in universities is sinking” and “A major reason for the mistrust is the universities’ suffocating left-wing monoculture.” It’s a fine point, to be sure, but explaining mistrust of “expertise” is different from explaining mistrust of “universities.” A few high-profile cases of stifled speech at universities may just be enough to account for public mistrust, though you’d need further evidence to support the same point about expertise in general.

That’s a minor misrepresentation, it’s true, but McCormick also fails to mention that the same footnote referring readers to Heterodox Academy, FIRE, and Quillette includes the line, “For other examples, see…” before citing: The Shadow University: The Betrayal of Liberty on College Campuses by Kors and Silvergate, Unlearning Liberty: Campus Censorship and the End of American Debate by Lukianoff, and The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting up a Generation for Failure by the same Lukianoff and Johnathan Haidt. Who can forget the Evergreen Incident, where Bret Weinstein was threatened by a group of student protesters in the middle of one of his classes? It was all over the news. It’s covered in detail in Lukianoff and Haidt’s book, along with the case of Nicholas Christakis at Yale, who was confronted by students protesting his racism—because he and his wife Erika argued that students were capable of choosing Halloween costumes themselves without being told how not to offend each other.

Maybe McCormick has a point, though, that fears about cancel culture are overblown because of “sensationalist anecdote chasing” by right-wing news outlets. How is this different from African Americans fearing for their lives after seeing YouTube videos of police shootings, when the numbers show they’re much more likely to be killed by someone who’s not a cop? For one thing, the numbers on police killings, though difficult to acquire and analyze*, are relatively simple compared to any effort at quantifying the risks posed by Twitter mobs or campus protesters. How many cases amounts to cause for valid concern? Another difference is that cancel culture operates on the logic of terror: activists publicly take down offenders in order to send a message to anyone else who may consider giving voice to a forbidden idea. They also send the message to other activists on how to deal with figures who don’t toe the line. I could be wrong, but I don’t think most cops are eager to have their fatal interactions with African Americans made more public.**

It should be noted too that organizations like Heterodox Academy and FIRE take it as their mission to promote diversity of opinion and protect free speech on campuses. Johnathan Haidt, one of Heterodox Academy’s founders, writes, “Nowadays there are no conservatives or libertarians in most academic departments in the humanities and social sciences.” In case you want some other sources he adds in a parenthetical “See Langbert, Quain, & Klein, 2016 for more recent findings on research universities; and see Langbert 2018 for similar findings in liberal arts colleges.” Sounds a bit monoculture-y to me. Signing on to Quillette, I had to search all of about two minutes for the tag “Free Speech,” which quickly helped me find an article about a composer who was mobbed and lost his job for criticizing arsonists at BLM protests. A continued search brought up several more cases. (I’ve actually witnessed a couple Facebook and Twitter debates firsthand that culminated in references to workplaces and threats to contact employers.)

I grant that Pinker could easily have been more precise with his citations; for instance, he could have cited FIRE’s report on the largest survey ever conducted on campus free expression, which found that “Fully 60% of students reported feeling that they could not express an opinion because of how students, a professor, or their administration would respond. This number is highest among ‘strong Republicans’ (73%) and lowest among ‘strong Democrats’ (52%).” FAIR also reports on the worrying trend of scholars being targeted and sanctioned for what was once protected speech:

Over the past five and a half years, a total of 426 targeting incidents have occurred. Almost three-quarters of them (314 out of 426; 74%) have resulted in some form of sanction.

The number of targeting incidents has risen dramatically, from 24 in 2015 to 113 in 2020. As of mid-2021, 61 targeting incidents have already occurred.

Still, Pinker’s book isn’t about free expression in schools or newsrooms. Remember McCormick elsewhere takes Pinker to task for not properly citing evidence to justify his use of a single term (doctrine). How long and in-depth does a citation need to be for a sidebar discussion in a book on a different topic?

It’s by now a standard retort among leftists that cancel culture is a myth promulgated by outlets like Fox News. That’s why McCormick only has to nod at Pinker’s example to signal to his readers what the book is really about. The Ad Fontes Media site, which assesses outlets for their bias and reliability, puts Slate, where McCormick published his review, in the hinterlands between “Skews Left” and “Hyper-Partisan Left.” (Quillette is incidentally closer to the center on the chart.) It’s not at all hard to imagine that McCormick would think fears of cancellation are overblown, since in this single article he’s shown himself willing and eager to defend any of the left’s central orthodoxies, regardless of the cost to his intellectual integrity. As a liberal historian, he’s far less likely to run afoul of campus speech codes than, say, a behavioral geneticist or evolutionary psychologist—to name two fields Pinker often reports on. (Pinker is no conservative though; he donated to Obama’s last campaign and released an embarrassing video of himself dancing in celebration of Trump’s 2020 defeat at the polls.)

From a Twitter discussion (commenter is not McCormick)

Why am I searching through footnote references about BLM and cancel culture in response to a review of a book about rationality? In earlier times, McCormick’s review would rightly be denounced as a politically motivated hatchet job. The thing is, though, I don’t think McCormick or many of his readers would be bothered much by this verdict. Largely as a consequence of intellectuals’ move from truth-seeking to social justice activism, the very one that Pinker and Haidt lament, it’s become far more acceptable to attack one’s fellow intellectuals on political grounds, regardless of the nominal topic of discussion. Many believe that you’re either helping to dismantle the hegemony or you’re helping to keep it in place. Pinker is allegedly doing the latter. He’s an old-fashioned modernist in a newfangled postmodern world.

So, McCormick quibbles with Pinker’s citations and I quibble with McCormick’s quibbles. What’s the point? For me, it’s the sad state of book reviewing, where McCormick can write an entire review calling Pinker out for insufficiently supporting his claims about hot-button political issues when the book he’s supposed to be reviewing is about something else entirely.*** Sure, McCormick offers up some arguments in addition to his political issues. Everyone claims to be rational, he insists, so what good can encouraging people to use reason possibly do? Everyone? Recall critical race theorist Richard Delgado’s challenge to “Enlightenment rationalism” for one prominent counterexample. Pinker answers the question himself, pointing out that many people think rationality is “overrated” because “logical personalities are joyless and repressed, analytical thinking must be subordinated to social justice, and a good heart and reliable gut are surer routes to well-being than tough-minded logic and argument” (xvi). I guess McCormick has never encountered anyone saying things like that.

McCormick’s strongest point is that, as Pinker admits, rationality must be in the service of some preestablished goal. What Pinker points to as an example of irrationality then might simply be an instance of competing goals. Let’s take Richard Delgado as an example. He says rationality is problematic because it might get in the way of racial justice. I imagine Pinker would respond, how do you know? (See page 42 of Rationality.) Why would you assume subordinating reason to social justice will lead to better outcomes? Even if it did, how would you know the approach worked? You’d have to use the tools of reason to find out and to convince others (unless you were prepared to use coercion). Tellingly, though, in this case, Pinker and Delgado actually share the same goal; they’re simply disagreeing about the best way to pursue it.

McCormick’s supposedly damning point about goals can really only apply to a subset of disagreements anyway. True, some people may have the goal of reinstating Trump as the president, while others have the goal of keeping him as far away from the oval office as possible. Encouraging both sides to be more rational will do nothing to settle the conflict. But isn’t getting one president elected over another a sub-goal, with the larger goal being to ensure the well-being of our nation’s children in the future. This goal too will be hampered by competing values in many areas, but it allows for at least some overlap of visions. Unless McCormick is suggesting that every instance of irrationality really reduces to differing goals, then the criticism can only apply to some disagreements and not others. The ones it doesn’t apply to can rightly be called irrelevant to Pinker’s discussion.

One of the things about McCormick’s review that will most frustrate anyone who’s actually read Rationality is that, contra McCormick’s central thesis, Pinker spends a lot of time describing how an idea that’s irrational from one point of view turns out to be rational from another. This includes BLM: “The goal of the narrative is not accuracy but solidarity,” he writes, explaining that “a public outrage can mobilize overdue action against a long-simmering trouble, as is happening in the grappling with systemic racism in response to the Floyd killing” (124-5).

It’s also not always the case that people are aware of which of their own goals are driving them. Recall Pinker’s line, quoted above, about “a shift in one’s conception of the nature of beliefs: from ideas that may be true or false to expressions of a person’s moral and cultural identity.” I’m sure if we ask McCormick if he was being rational when writing his review, he’d say yes. But I suspect his efforts were in large part motivated by his desire to signal his leftist bona fides to the other members of his tribe. (I’m probably doing the same thing right now, just for a different tribe.) If he has these two competing goals, might he be pursuing one rationally and the other irrationally?

Here’s the larger point: regardless of whether I can convince McCormick that his review is irrational, anyone reading the exchange can get the takeaway message that to be rational, one must try to avoid the trap of letting our desire to belong and elevate our status distort our view of the matter in question. How might you do that? Well, seeking out friendships with people holding different views could help. Engaging in honest, open debates with people with competing perspectives wouldn’t hurt. It may even be a good idea to simply ask yourself, “Is this something I believe because I’ve really looked into it? Or is it just what the people around me think I should believe? Am I trying to impress everyone by taking down some figure they dislike?” The outcome of the debate about whether McCormick’s review is rational is irrelevant as long as the goal is to help people understand the principle and apply it to their own reasoning.

Of course, if it really were the case that Pinker’s book bursts at the seams with dubious examples of the irrationality of one political group, that would amount to a good reason to believe he had ulterior motives. But we’re talking about a few passages and a handful of lines in a 340-page book. I’ve already quoted nearly all of them in this post. And he spends just as much time focusing on the reasoning behind showing up at a pizzeria with an assault rifle or storming the Capitol. The real reason McCormick likes the point about rationality serving goals, I suspect, is that it allows him to argue (mistakenly) that determining what’s rational “means choosing some values and imposing some goals.”

That’s what McCormick wants us to believe Pinker is really up to in the pages of Rationality, imposing his values and goals, anointing himself arbiter of all things rational, and pointing readers to his own weird and dystopian vision of the world. McCormick writes,

This paradox of defining reason as a universal means while invoking it as a specific norm, which is what Pinker specializes in, has wider political implications now, much as it did in the Enlightenment. Remember the San hunters? It was one thing to appreciate their fine calculations when the point to be made was the universality of reason as a human tool. But by the time the theme of reality vs. mythology returns, late in the book, rationality has new heroes: the people Pinker identifies as W.E.I.R.D. (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic) “children of Enlightenment.” Unlike the San—indeed, unlike everyone else—these champions not only possess the tools of rationality but “embrace the radical creed of universal realism”. To them belongs an “imperial mandate … to conquer the universe of belief and push mythology to the margins,” so that a “technocratic state” can act on their rational beliefs. Welcome to Steven Pinker’s Kingdom of Ends.

Ah, the axe McCormick has come to grind is very large and very blunt indeed. Having argued that Pinker is using his discussion of rationality as a Trojan Horse to promote his goals and values, he paints a final picture of a world ruled by a bunch of the Enlightenment champion’s clones.

If you’ll forgive me one last lengthy block quote, you can see McCormick’s distortions in action. First, it’s in a chapter titled, “What’s Wrong with People?” in which Pinker attempts to explain why it seems like people are so bad at reasoning. In one section of the chapter, he posits “Two Kinds of Belief: Reality and Mythology”, pointing out that throughout most of our run here on Earth, we humans have let the two realms peacefully coexist in our minds. This was partly because we lacked tools like telescopes and computers and sophisticated statistical methods. But part of it is simply that we lacked a commitment to applying reason to certain questions. The passage begins quoting Bertrand Russel: “It is undesirable to believe a proposition when there is no ground whatsoever for supposing it is true.” Pinker writes,

Russell’s maxim is the luxury of a technologically advanced society with science, history, journalism, and their infrastructure of truth-seeking, including archival records, digital datasets, high-tech instruments, and communities of editing, fact-checking, and peer review. We children of the Enlightenment embrace the radical creed of universal realism: we hold that all our beliefs should fall within the reality mindset. We care about whether our creation story, our founding legends, our theories of invisible nutrients and germs and forces, our conceptions of the powerful, our suspicions about our enemies, are true or false. That’s because we have the tools to get answers to these questions, or at least to assign them warranted degrees of credence. And we have a technocratic state that should, in theory, put these beliefs into practice.

But as desirable as that creed is, it is not the natural human way of believing. In granting an imperialistic mandate to the reality mindset to conquer the universe of belief and push mythology to the margins, we are the weird ones—or, as evolutionary social scientists like to say, the WEIRD ones: Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic. At least, the highly educated among us are, in our best moments. The human mind is adapted to understanding remote spheres of existence through a mythology mindset. It’s not because we descended from Pleistocene hunter-gatherers specifically, but because we descended from people who could not or did not sign on to the Enlightenment ideal of universal realism. Submitting all of one’s beliefs to the trials of reason and evidence is an unnatural skill, like literacy and numeracy, and must be instilled and cultivated.

Suddenly, the paradox McCormick trips over seems a lot less problematic; applying reason in some contexts is natural but applying it in all contexts is not. And what McCormick holds up as a prescriptive vision for the world turns out to be a descriptive—even somewhat humble—answer to the question of why people find rationality so difficult.

Most importantly, McCormick dishonestly claims Pinker assigns an “imperialistic mandate” to the WEIRD—a group McCormick doesn’t seem to realize he belongs to as well—when he in fact writes that the WEIRD grant this mandate “to the reality mindset.” Pinker’s “Kingdom of Ends”—a reference to Kant’s idea that society should treat every individual not as a means but as an end unto themselves—now looks quite a bit more open-ended and far less autocratic. Is it going too far to suggest McCormick, in seeking out diverse tidbits to connect into a pattern revealing a dangerous hidden plot, must be relying on the same kind of conspiracy theory mindset that’s killing the vaccine hesitant and driving armies of Trump supporters to agitate for his reinstatement after a rigged election?

The reason people like Pinker and me are worried about activism invading intellectual spheres is that it undermines the trust the public once rationally placed in truth-seeking institutions. As long as universities, the editorial boards of scientific journals, and the staffs of journalistic websites openly proclaim their commitment to pursuing political agendas—no matter how well-intentioned—the public has good reason to doubt their commitment to truth and just as good reason to treat them each as just another special interest group. McCormick hasn’t written a review of Rationality so much as he’s participated in a campaign against Pinker, who many feel must be denounced because he doesn’t hold all the proper political opinions. (McCormick continues this campaign on Twitter if you’re interested.) A book reviewer should strive to represent the author’s work honestly and fairly, offering readers an accurate sense of what it’s about, how successfully the author is in meeting his goals, and what it’s like to read. McCormick’s review fails on all these counts, as you can see in comparing the passages above. Perhaps, he simply had other goals.

*****

* Data from a recently published analysis shows that police killings have been underreported by a factor of 55.5% over recent decades. This changes the math on relative risks, but since the numbers are still so small, the outcome isn’t markedly different.

** Since I’ve already had someone complain about my “take” on BLM and police shootings, and because I fear [rationally?] being mobbed myself, let me stress here that I’m in no way giving my own personal take on these subjects here—and I don’t believe Pinker is giving his in Rationality either. The point here is to evaluate the underlying logic of some of the ideas and popular reasoning associated with the subjects. Later in the essay, you’ll find an example of how Pinker’s reasoning about BLM is more nuanced than his pointing to any single error in reasoning might suggest.

*** McCormick gave some brief, rather snarky, responses to this essay on Twitter. Most of his points were against straw men (in my opinion), but he did correctly call attention to this one line that was misleading. I complained of McCormick “bashing Pinker’s politics” throughout his review; he doesn’t. I’ve revised the line to be more precise and correct the error.

Also read:

THE FAKE NEWS CAMPAIGN AGAINST STEVEN PINKER AND ENLIGHTENMENT NOW

And:

And:

NAPOLEON CHAGNON'S CRUCIBLE AND THE ONGOING EPIDEMIC OF MORALIZING HYSTERIA IN ACADEMIA

Violence in Human Evolution and Postmodernism's Capture of Anthropology

Anthropologists Brian Ferguson and Douglas Fry can be counted on to pour cold water on any researcher’s claims about violence in human evolutionary history. But both have explained part of their motivation is to push back against a culture that believes violence is part of human nature. What does it mean to have such a nonscientific agenda in a what’s supposed to be a scientific debate?

Anytime a researcher publishes a finding that suggests violence may have been widespread over the course of human evolutionary history, you can count on a critical response from one of just a few anthropologists. No matter who the original researcher is or what methodological and statistical approach are applied, one of these critics will invariably insist the methods were flawed and the analysis fails to support the claim. To be fair, these critics do have a theoretical basis for their challenges. By their lights, violence, especially organized, coalitional violence, emerged in complex societies as the result of differential access to prized resources. Hunter-gatherers and horticulturalists tend to roam widely, so they don’t accumulate much by way of property over their lifespans, which means there’s nothing much for them to fight over—at least according to the theory.

But these anthropologists also openly admit to a political agenda driving their engagement in the controversy. The idea that violence was rampant over the course of human evolution could imply that humans evolved to be violent—that violence is in our genes. And, if the view that humans are innately and hence irredeemably violent is allowed to take hold, war hawks can more credibly brush aside talk of peace as naively utopian. As Brian Ferguson, the single most cited advocate of the view that our hunter-gatherer past was markedly more peaceful than our civilized present, says in a documentary about the history of controversial research among the Yąnomamö of Brazil and Venezuela, “If we’re going to work against war, we need to work against the idea that war is human nature” (36:26). In other words, these scholars see a direct line connecting the science of human violence and the politics of war. If you want peace, according to this line of thinking, you must not let the contention that violence was widespread throughout human evolution go unchallenged.

Of course, admitting to an agenda like this opens you to accusations of ideological bias. Are scholars like Ferguson insisting the evidence of violence in the Pleistocene is weak because they genuinely believe it is? Or is it because they believe they can prevent wars by convincing enough people it is? If some new evidence clearly demonstrated their view to be in error, would they admit this publicly? Or would they continue singing the same tune about our notionally peaceful past while casting aspersions on whoever reported the new evidence? The inescapability of questions like these are what makes it so odd that anyone would admit to a political agenda in a scientific context. So how do they justify it?

Image by Canva’s Magic Media

Anthropology is an odd discipline. The political homogeneity of people in the field has made it particularly vulnerable to the encroachment of a certain set of ideas from nonscientific disciplines. Postmodernism is rife in the field, and one of the central tenets of postmodernism is that there are more or less covert political motivations driving every intellectual or artistic endeavor. From this perspective, all the scholars proclaiming their ambition to promote peace are doing differently from their seemingly apolitical colleagues is explicitly owning up to their political agenda.

(Many scholars, no matter how well the label fits, chafe at being called postmodernist, complaining that the term is too vague or that it’s too broad to be meaningfully applied to them. I suspect this is mostly an effort at muddying the waters, but here I’ll simply define postmodernism as a philosophy that focuses on the role of power relations—oppressors versus the oppressed—in knowledge formation and which thus encourages a high degree of skepticism toward scientific claims, especially those that can be viewed as in any way negatively portraying or impacting some marginalized or disempowered group.)

This is where the situation gets scary, because the flipside to postmodernists’ presupposition of political motives is that any researcher who reports evidence of pre-state conflict or any theorist who emphasizes the role of violence in human evolution must likewise have an agenda—to promote war. This must be true even if the anthropologist in question explicitly denies any such agenda. Here’s Douglas Fry in an interview with Oxford University Press:

When the beliefs of a culture hold that humans are naturally warlike, people socialized in such settings tend to accept such views without much question. Cultural traditions influence the thinking and perceptions of scientists and scholars as well. I suspect that one reason that retelling this erroneous finding is so common is that it supposedly provides “scientific confirmation” of the warlike human nature view.

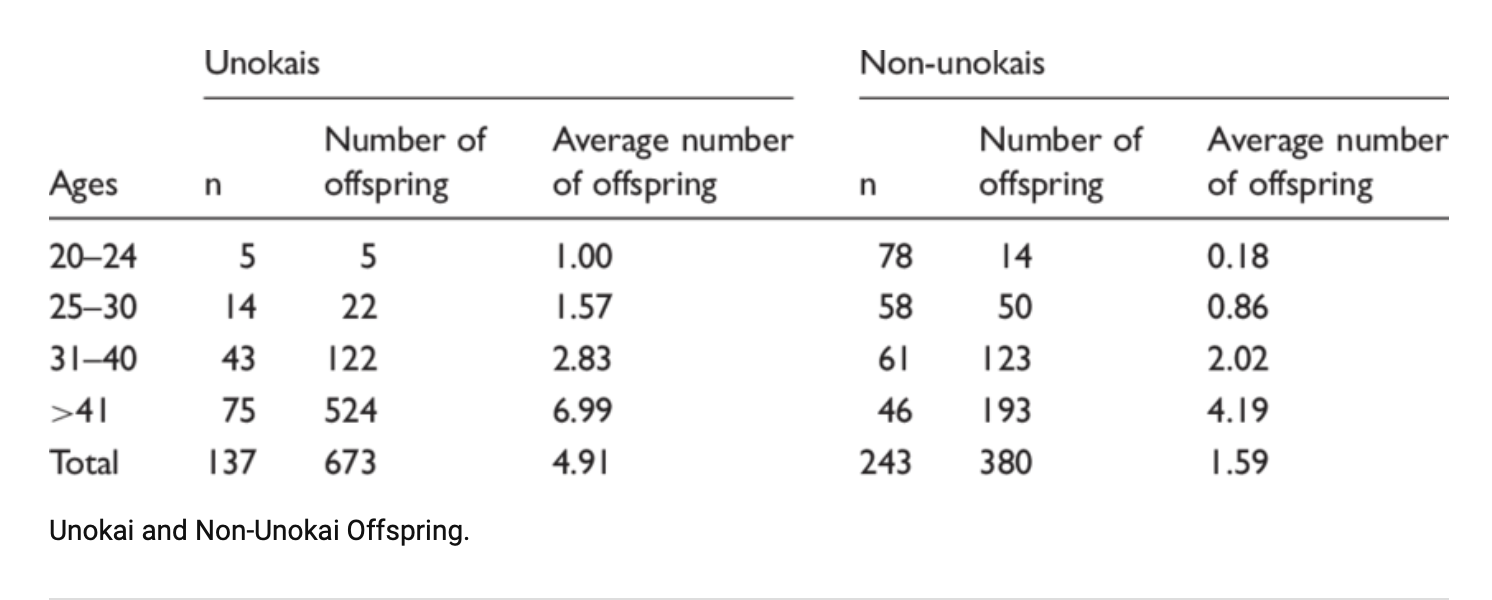

The specific “erroneous finding” Fry refers to is that Yąnomamö men who kill in battle father more children than those who never kill anyone. It was published by Napoleon Chagnon in Science, and Ferguson promptly responded with his criticisms, which Fry insists completely undermine Chagnon’s analysis. Whether the finding has truly been overturned is contested to this day, but Fry’s interview demonstrates a common pattern: Yes, of course, the evidence proves the findings about violence wrong, the postmodern anthropologist will claim, but just for good measure let’s also indict the anthropologist who reported them for his complicity in perpetuating a culture of war. They never seem to realize that the second part of this formula undermines the credibility of the claim made in the first.

Chagnon’s Findings on Unokai (Killers)

Whether you accept the proposition that politics percolates beneath the surface of all forms of intellectual discourse, you can see how the postmodern activist stance provides a recipe for overly politicized debates, where instead of arguing on the merits of competing views, scholars are enjoined to imagine they’re engaged in righteous combat against their morally compromised colleagues. If you’re more of a traditional scientist, meanwhile—i.e., if you don’t take postmodernism seriously—then the sanctimonious tone taken by your detractors will strike you as evidence of an ideological commitment to sweeping inconvenient evidence under the rug.

If you’ve ever debated someone who insists on arguing against your presumed ideological agenda while completely ignoring major parts of the case you’re actually making, you know how maddening and futile such exchanges can be. Indeed, many of the rules of scientific discourse—rules postmodernists believe only serve to allow justifications for oppression to fly in under the radar—exist to help intellectual rivals avoid the deadlock of competitive mind-reading and the attribution of sinister motives. Nonetheless, many scholars today take it for granted that science not only can coexist with postmodernism but that science needs postmodernism to prevent the reemergence of evils like eugenics, scientific racism, or colonialist exploitation. What they don’t understand is that you can’t take in the Trojan horse of an idea like ulterior agendas without opening the gates to the entire army of postmodern tenets. Once you let morality or politics or ideology into the debate, then that debate is no longer scientific; there’s no having it both ways.

Ah, but the postmodernist critic will object that it’s impossible not to let politics and ideology into any debate. Pure objectivity is a fantasy. So, if hidden agendas and biases are going to continue operating despite our best efforts, we may as well call them out. And, having exposed them to the light of day, we may as well admit that our disagreement is as much political as it is scientific. As Allison Mickel and Kyle Olson write in a 2021 op-ed for Sapiens titled “Archaeologists Should Be Activists Too,”

There are still some who argue that scientists maintain their authority only when they remain objective, separate from current political concerns. Many academics have decried this view for decades, demonstrating that fully objective science has always been more of a myth than a reality. Science has always been shaped by the contemporary concerns of the time and place in which research occurs.

This brings us back to the permissibility, even the moral necessity, of infusing our science with postmodernism.

But this point rests on a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of science. The point was never to thoroughly eradicate bias or to deny that individual perspectives are always shaped by forces beyond the individual’s awareness. The point is that by taking measures to reduce bias we can engage in more fruitful discussions that are more likely to lead to real insights and discoveries. True, bias can never be fully eliminated. Nor can pathogens ever be thoroughly annihilated from an operating theater. That doesn’t mean anyone should undergo surgery in a gas station bathroom. Seeing countless scientific debates degrade into petty moralizing and name-calling free-for-alls between tribalized groups of intellectuals for the past decade on social media ought to have convinced us all that at least trying to stick to the facts while avoiding ad hominem attacks has a lot to recommend it.

The public trusts science—insofar as this is still true—precisely because scientists make a point of examining evidence as objectively as humanly possible while doing whatever they can to minimize bias. But, once scientists start proclaiming their activist agendas, they forfeit that trust, giving the public no reason to see scientists and scientific institutions as any different from all the other special interest groups vying for attention and resources. Indeed, this loss of trust is already well underway, as the Covid-19 pandemic made abundantly clear.

There are at least two other major problems with the melding of postmodernism onto science. The first is that, while it may be true that we all operate on unconscious beliefs and agendas, there currently exists no method that’s even remotely reliable for determining what those beliefs and agendas are. If you accuse some anthropologist of reporting on the violence she observed among the people she’s studying merely because she favors military expansionist policies, you can expect her to reply that, no, she’s simply telling everyone what she witnessed. How, without resorting to spectral evidence, would you then go about establishing that she in fact doesn’t know her own true motivation? How can others check the work you put into uncovering this hidden agenda? The awkward reality is that postmodern anthropologists routinely insist that their rivals have some reactionary agenda even when those rivals are on record supporting progressive causes.

To see how catastrophically the attribution of unconscious motives can go awry, take a look at some of the earliest theories about the inner workings of the mind from the turn of the last century. Freud can be credited with the revelation that much of what goes on in our minds is outside of our awareness. But nearly every theory he put forth based on that revelation turned out to be wrong—and in the most grotesque ways. As the theory of the Oedipus Complex, which posits that infant boys want to kill their fathers and marry their mothers, ought to make clear, without sound methods for examining the contents of our unconscious minds, all this speculation about hidden biases and motivations all too easily morphs into fodder for the formation of cultic beliefs.

The postmodernist anthropologists counter this point by insisting they’re not interested in the contents of individual minds. Rather, they’re interested in the impact those individuals’ actions and statements have on society. Whether, say, Napoleon Chagnon really intended to bolster the rationale for sending troops to Southeast Asia is beside the point. His case for widespread violence in human evolutionary history had that effect regardless of his intentions.

But did it really?

Leaving aside the question of whether someone should be held morally accountable for outcomes he didn’t intend, we still must ask how the postmodernists know what the impact of an idea will be—or has been. How do they know Chagnon’s work had the effect they claim it had? Is there any evidence that Kennedy or Johnson or any of the top generals were even aware of Chagnon’s work among the Yąnomamö? (His infamous paper on Yąnomamö warriors having more children wasn’t published until 1988.) Are there any survey data tying beliefs about pre-state warfare to voting behavior? As is the case with their efforts at revealing an individual’s unconscious motives, the absence of any viable methods for examining the societal impact of ideas essentially gives postmodern critics a blank check to assert whatever’s on offer from their darkest imaginings.

This leads into the next flaw in the campaign to blend postmodernism with science. The connection between beliefs about human nature and the political or moral convictions one holds is hardly straightforward. Personally, I’ve gone back and forth on the issue of how violent our Pleistocene ancestors were, but I have never, and would never vote for any politician campaigning on the glories of conquest. Likewise, I believe there are consequential differences between male and female psychology, but I have never, and would never vote for a candidate who insists women should be banned from certain professions because of these differences. Indeed, I hold many views that are more compatible with the conception of human nature that gets ascribed to those with conservative politics, but I’ve never voted for a Republican in my life. In this supposed contradiction, I’m far from alone.

Survey data show that adaptationist psychologists, whose stance allegedly serves to perpetuate the political status quo, are no more likely to vote conservative than any other psychologists, all of whom tend to be left-leaning. This however isn’t to say political leanings have no connection to the beliefs of anthropologists. One large, in-depth survey showed that while people in the field are almost invariably on the left, some are much farther to the left than others. And those who identify as Radical, as opposed to Liberal or Moderate, are more likely to agree with the statement, “Foraging societies in prehistory were more peaceful.” They’re also more likely to disagree with the statement, “Advocacy and fieldwork should be kept as separate as possible to help protect the objectivity of the research.” Not surprisingly, Radicals are also more likely to agree that “Postmodern ideas have made an important contribution to anthropology.”

One of the most recent flareups over the role of violence in human evolution was fomented by Steven Pinker’s book The Better Angels of Our Nature, which argues that the story of civilization is one of progress toward greater peace. If Western societies are becoming less violent over time, then they must have been more violent in the past. To demonstrate this, Pinker includes a graph showing what percentage of various populations likely died at the hands of other people. (Like clockwork, Brian Ferguson went on record insisting the numbers for pre-state societies are exaggerated.) Many anthropologists and native rights activists believe the publication of these figures is unconscionable. But the interesting point here is that Pinker cannot be using his evidence of pre-state violence as a justification for war, because the whole point of his book is to examine the causes of the documented decline in violence. Let me emphasize this point: Pinker argues both that violence was rampant in our evolutionary past and that we as a species are entirely capable of transcending that past. Indeed, we’re not only capable of reducing violence; we’ve been doing it for centuries. Better Angels thoroughly obliterates the notion that believing violence played a significant role in human evolution makes one a de facto advocate for war in the present.

There are plenty of other instances of this disconnect. Anthropologist Agustin Fuentes recently raised a kerfuffle by writing an op-ed for Science about all the racism and misogyny on display in Darwin’s Descent of Man. Fuentes contends it’s important to see that even someone as brilliant and insightful as Darwin was still a slave to the prejudices of his day, which ought to make us all consider how big of a role prejudice may be playing in our own thinking. To make this point, Fuentes explains how Darwin got so much about race right: he knew no clear line separates one race from another and that no feature is found in any one race that’s absent in all the others. Most importantly, as an outspoken abolitionist, he knew that slavery is evil. Fuentes can’t hide his frustration with Darwin for getting so close without quite reaching the modern understanding of race as a social construct. What Fuentes is missing is that Darwin demonstrates that it’s not necessary to believe all races or all individuals are completely equal in every regard for one to insist that all races and all individuals should be treated as equally human. The scientific belief in group differences, or gender differences, or individual differences, contra the postmodernists, can live peacefully alongside a commitment to equal and universal human rights.

Politics can never be completely decoupled from science. Beliefs about human nature can’t be completely disentangled from moral reasoning. But the lines connecting theory to policy, or paradigm to advocacy, are seldom as straight as postmodernists would have us believe. The notion that you can improve the circumstances of indigenous peoples, or reduce racism, or make way for military drawdowns simply by criticizing intellectuals you disagree with and making accusations against them you can’t prove strikes me as childish and absurd. That’s because my own deepest intuition is that to solve a problem it’s best to first try to reach as thorough an understanding of that problem as possible. Any insistence that activism supersede science is based on the pretense of already having the very answer you’re supposedly seeking. What if humans really are naturally violent in some circumstances? Isn’t it better to honestly investigate what those circumstances are than to zealously promote a fantasy of violence being some civilization-induced aberration from our history of angelic communalism?

For many people, the addition of a second reason to reject an idea probably makes the criticism that much more plausible. Not only is the evidence not a hundred percent airtight, but if people believe this idea there’ll be hell to pay. But scientists ought to recognize the fallacy of an argument from adverse consequences when they see it. Plenty of anthropologists catch on to this trick when it’s played by creationists: If people believe they descended from apes, they’ll start to behave as if they had. The second part may seem plausible, but it still requires evidence to establish. More importantly, the first part may be true even if the second is. Scientists trained to recognize such flaws in human reasoning ought to know focusing on the reasons you want a claim to be true does nothing but detract from your credibility.

If your priority when engaging in science is to seek the truth, that will be reflected in your readiness to change your mind when new evidence emerges. If on the other hand your main concern is managing what ideas make their way into the prevailing culture, then you have no right to call yourself a scientist. What you’re trying to be is some sort of preacher, but what you’re probably engaging in more than anything else is censorship. Scientists are supposed to be truth-seekers first and foremost, not social engineers. Activism is well and good, but if you mix it with science, you degrade the integrity of both. Yes, neither you nor anyone else will escape bias and cultural programming, but that should make postmodernists just as intellectually and morally humble as they demand scientists be. The best way to rein in your bias after all is to engage regularly in discourse with people who hold different views and beliefs. Given postmodernism’s woeful effect on intellectual discourse of any sort, it seems a catalyst for more, not less bias, and more, not less tribalism.

Also read:

Just Another Piece of Sleaze: The Real Lesson of Robert Borofsky's "Fierce Controversy"

The Self-Righteousness Instinct: Steven Pinker on the Better Angels of Modernity and the Evils of Morality

“The World until Yesterday” and the Great Anthropology Divide: Wade Davis’s and James C. Scott’s Bizarre and Dishonest Reviews of Jared Diamond’s Work

Napoleon Chagnon's Crucible and the Ongoing Epidemic of Moralizing Hysteria in Academia

From Darwin to Dr. Seuss: Doubling Down on the Dumbest Approach to Combatting Racism

The anthropologist Agustin Fuentes recently published an editorial in the journal Science to mark the 150th anniversary of the publication of The Descent of Man by Charles Darwin. What did Fuentes see fit to say about the great man of science and his still controversial but undoubtedly brilliant work? Well, it turns out some parts of the book are less than charitable to people who aren’t of European descent. Some of the things Darwin wrote about women are pretty awful too. What are we to make of this?

If you believe our society is deeply racist, how do you go about changing it? You may start by trying to change your country’s laws, but what happens if the injustice persists after racism has been officially outlawed? Further, what happens when you realize large swaths of the population fail to see racism as a serious problem?

This challenge lies at the heart of many bizarre trends today among not just activists but academics, journalists, and even businesspeople. Why, for instance, are we suddenly so concerned with whether historical figures lived up our modern moral standards? What can we hope to achieve by pointing out all the areas in which they fell short?

This trend is partly the natural outcome of a misdiagnosis. Racism is embedded in our culture, it is argued, so we need to change our culture to eradicate racism. That begins with a reevaluation of the characters we hold up as heroes. Dr. Seuss, for instance, is read by millions of kids. Well, it so happens that Dr. Seuss early in his career created some racist propaganda. But does anyone outside of graduate school ever see these WWII-era cartoons? Who knows? Either way, it warrants a deeper look at the books so many of us do read, because the bringing to light of this man’s subtle racism, the thinking goes, will likely raise our collective understanding of how racism works and how we can recognize it. So, let’s write some academic papers examining the racism implicit in, say, The Cat in the Hat. Even better, let’s cease publication of some of Dr. Seuss’s more dubious early works like And to Think that I Saw It on Mulberry Street.

One problem here is that it’s unlikely in the extreme that any nonracist person ever read a Dr. Seuss book or saw a Dr. Seuss cartoon and was transformed into a racist for having done so. It’s only slightly less unlikely that anyone was ever nudged into being even slightly more racist for having read these works. Starting a conversation about Dr. Seuss’s alleged racism, at least as part of an effort at combatting racism in general, is predictably and resoundingly futile. But there’s an even bigger problem the activist academics fail to appreciate. We love our heroes. People love Dr. Seuss. So, if you campaign to stop some of his books from being published, or if you simply argue publicly that he was a racist, not only are you going to fail to reduce racism by even the most negligible margin, you’re also going to provoke a backlash that could easily hamstring less ill-conceived efforts in the future.

The response to Dr. Seuss’s estate ceasing to publish some of his books—and countless high-profile liberals defending the move as something other than another instance of “cancel culture”—was that these books jumped to the top of the bestseller lists. Along the way, many centrist liberals (like me) and nearly all conservatives became less receptive to any messages about alleged racism. You can imagine someone saying something like, “You say this guy’s a racist, huh? You idiots think Dr. Seuss was a racist.” And there’s no doubt the political party least likely to push for reforms that may lead to better conditions for minorities is the very one that’s going to be campaigning on the idiocy of the folks who think “canceling” Dr. Seuss was a stellar idea.

The mistaken assumption leading to debacles like this is that prejudice and racial animosity are entirely cultural. The reality is that all over the world people tend to be suspicious of others who are different from them. And it only takes a few bad experiences to push this suspicion into full-blown hatred. This isn’t just a white people problem. It’s a human problem. Further, the answer to why some groups within a larger society don’t do as well as others isn’t always to be found in the attitudes and beliefs of the groups that are doing better. Inequality, including racial inequality, arises from a multitude of factors. I have little doubt one of the factors behind racial inequality in America today is our racist history. But I don’t think tearing down a statue of Robert E. Lee—or anyone else for that matter—is going to help at all. The issue is simply too complicated to be addressed by calling a bunch of people racists and striking their names from history.

Okay, so the Dr. Seuss episode was silly. But what about historical figures who made explicit claims and arguments that can be used to justify racial oppression? The anthropologist Agustin Fuentes recently published an editorial in the journal Science to mark the 150th anniversary of the publication of The Descent of Man by Charles Darwin. What did Fuentes see fit to say about the great man of science and his still controversial but undoubtedly brilliant work? Well, it turns out some parts of the book are less than charitable to people who aren’t of European descent. Some of the things Darwin wrote about women are pretty awful too. To be fair, Fuentes acknowledges that Darwin was a “trailblazer.” In a later podcast episode with science writer Robert Wright, he goes so far as to say that Darwin is one of his heroes. All the more reason, he explains, to challenge the “problematic” ideas he put forth in his magisterial work on human evolution.

Fuentes doesn’t want people to stop reading Darwin. In fact, he insists what he wants is for us to read more Darwin, so we can appreciate the genius in all his complexity, which means acknowledging he wasn’t as great as he could have been. The crucial lesson Fuentes gleans from Darwin’s failure to see through to our modern understanding of race—when he took so many tantalizing steps in that direction—is that as much of a genius as he was, even he couldn’t see past the prejudices of his day. It’s enough to make you wonder, what makes Fuentes so confident he can see past the prejudices of his own day?

It’s a safe bet that the publication of Fuentes’ editorial will make not a single soul a scintilla less racist, though I’m certainly open to evidence to the contrary. Nor will Fuentes’ writing do anything to improve the material well-being of minorities in this country or any other. I would also have predicted, had I known about the article in advance, that it would provoke a heated backlash. As it happened, I watched that backlash play out on Twitter. (I even participated in it.) The people who read editorials in Science, mirabile dictu, love Darwin. And many of them were less than pleased to see his name dragged through the mud in the nation’s most prestigious scientific journal.

Was Darwin really racist? Fuentes, with his considerable geeky charisma, is the type of pedant who would ask you six other questions before answering that one, just to key you in on how complex of an issue we’re dealing with. What do we even mean, for instance, by the term racist as applied to someone in the Victorian Age, an era that had neither our modern understanding of racism nor our modern scientific understanding of population genetics? Both our morals and our science have evolved. And, unlike biological evolution through natural selection, the evolution of our mores and theoretical frameworks represents clear progress.

Fuentes credits Darwin for pointing out that races can be difficult to categorize because each race grades into the others with no bright line demarcating one from the next. Darwin also realized that there were no single traits or features found solely among the members of one race that could be used to distinguish them from members of another group. He even argued against the hypothesis that racial differences arose due to natural selection (an idea that could be taken to imply one race was somehow better adapted to its environment, i.e., superior). In addition, Darwin was personally aghast at the cruelty of slavery, which was why he supported abolition. (He was in fact highly sensitive to suffering in all its forms, whether in animals or humans—of any race.)

So, he was sophisticated enough, morally and scientifically, to understand these truths, but he nonetheless failed to arrive at the understanding of race Fuentes advocates, that it’s a biologically incoherent concept. Worse, he accepted the hierarchical ranking of the races that was prevalent in his time, with Africans, Native Americans, and Australian aborigines at the bottom and Caucasians at the top. Meanwhile, at multiple points in his writing he refers to the lesser cognitive capacity of women.

The impression we get of Darwin then is that he was intensely empathetic, had great prescience and insight, but that he also harbored some loathsome beliefs. Those observations alone would have made for an outrageously banal editorial. I think “Well, duh” would be the proper response. He was writing after all in the years just after slavery was abolished in the US. As historian of science Robert J. Richards writes in an essay defending Darwin from charges of racism leveled by creationists, “When incautious scholars or blinkered fundamentalists accuse Darwin or Haeckel of racism, they simply reveal to an astonished world that these thinkers lived in the nineteenth century.” Who are any of us to fault someone for not arriving at conclusions we had the benefit of being taught directly? But Fuentes raises the stakes at a couple points in his essay. For instance, he claims that Darwin

went beyond simple racial rankings, offering justification of empire and colonialism, and genocide, through “survival of the fittest.” This too is confounding given Darwin’s robust stance against slavery.

That first line is the one Robert Wright took issue with, beginning the exchange that culminated in the two conversing on Wright’s podcast.

Did Darwin really offer justification for evils like colonialism and genocide? Wright points out the phrase “survival of the fittest” wasn’t coined by Darwin, and he let it be known he wasn’t too keen on its use. But is there anything in Descent that would imply Darwin thought genocide was a good idea? Fuentes points to sections where he describes the process of one race supplanting and exterminating another through conquest. Wright then poses the appropriate follow-up: isn’t there a difference between explaining and justifying? Fuentes doesn’t have a good response to this question. He merely says that by “justification” he means “the right and reasonable explanation for what’s happening in the world” before going on to agree with Wright that he’s relying on the naturalistic fallacy—taking what’s natural for what’s moral—that Darwin himself challenged.

Fuentes’ mealy-mouthed response to Wright’s valid criticism could be ascribed to simple dishonesty, or if we’re charitable we could ascribe it to sloppiness. The word “justification” has the connotations it does. But I think he was simply bowing to the conventions of the genre he’s writing in, with its cliched expressions like “problematize” and its inbuilt insistence that whatever mistakes Darwin made were “harmful.” This type of criticism is required to include references to the purported harm or injury caused by the “problematic” statements under scrutiny, thus providing justification for the project of reevaluation. The part of Fuentes’ essay that most bothered me personally, though, is where he extends this point about the harm of letting Darwin’s ideas go unchallenged.

Today, students are taught Darwin as the “father of evolutionary theory,” a genius scientist. They should also be taught Darwin as an English man with injurious and unfounded prejudices that warped his view of data and experience. Racists, sexists, and white supremacists, some of them academics, use concepts and statements “validated” by their presence in “Descent” as support for erroneous beliefs, and the public accepts much of it uncritically.

Fuentes could set me straight on this with some quotes from the white supremacist academics he refers to, along with some survey data showing that the public accepts their statements uncritically. But my sense is that he included these lines not because he’s familiar with any such evidence but because he needs them to convince readers that his highlighting of Darwin’s mistakes is morally important, even imperative.

Fuentes may be right that there are people today who appeal to Darwin’s authority to support their racist arguments. But if there are, I doubt there are many. Darwin’s is the last name you’d expect to hear in any encounter with a white supremacist. In my experience, you’re much more likely to get Bible references. On the other hand, it’s far too easy for me to imagine a naively self-righteous college kid saying something along the lines of, “Darwin, seriously? You know that guy was racist as hell, don’t you?”

Historically, it’s undoubtedly true that the theory of natural selection has been held up as a justification for atrocities. But, again, such justifications relied on the naturalistic fallacy Darwin himself avoided. And it’s probably the case that those atrocities would have been committed even if natural selection had never been propounded. Racial hierarchies trace back to the medieval Great Chain of Being. Darwin wasn’t around to provide justification for the transatlantic slave trade (which he abhorred). As they once did with religion, modern people now often use science the way the proverbial drunk uses a light post: for support, not illumination. (Curious that the far left has found common cause with the creationist right in their mission to tar Darwin as complicit in modern evils.) This gets at the central point of confusion I see tripping up scholar/activists like Fuentes.

In looking for the roots of racism, too many academics flatter themselves by looking to the history of ideas and scholarship, as though every evil attitude and belief can be traced back to some scientist or philosopher just like them, only less moral. If that were the case, it would make sense to go back to those originators in an effort to root out the evil. But what if racism doesn’t merely seep into our minds from our cultural milieu? Indeed, research with infants suggests the first stirrings of racial bias are evident as early as six months. This bias may be solely attributable to a preference for what’s familiar. It may be attributable to inborn favoritism toward those similar to us. But, at 6 months, it’s certainly not attributable to reading books like The Descent of Man—or for that matter, I Saw It on Mulberry Street.

Likewise, if you were a world traveler in times of yore, you didn’t need some aristocratic naturalist to tell you that the natives you were encountering weren’t as intellectually sophisticated as the people back home. You could see it with your own eyes (or at least that’s how it would have seemed). Fuentes may imagine that were he himself in one of those situations of first contact he would think something like, “These hunter-gatherers are obviously exactly the same as us Europeans but for the higher melanin content of their skin, their different culture, and the level of their technological advancement,” but he’d be forgetting the deep cultural influences he himself has been subject to. The more obvious conclusion anyone would draw is that the natives simply aren’t as intelligent as civilized people.

That conclusion is wrong of course. We know from works like Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel that there are sufficient geographical and historical reasons for the varying levels of technological advancement achieved by peoples in different regions of the world to make the intelligence hypothesis unnecessary. But that book wasn’t written until 1997. For Fuentes, however, the right answer is so clear, he can’t help being frustrated at Darwin for not arriving at it. Why is Fuentes so blind to all the reasons people might draw racist conclusions that have nothing to do with books or the dominant culture?

One commenter took Fuentes to task for falling prey to a strange reverse of the curse of knowledge. This is the curse that makes experts so lousy at explaining anything in their field of expertise because we humans all struggle to take the perspective of people who don’t know the things that we know. Fuentes makes the opposite mistake, believing no one knows about Darwin’s racist and sexist statements, when almost everyone who bothers reading his books almost certainly understands that his beliefs reflect the attitudes of his time. It’s an important point. And this thoroughgoing lack of perspective regarding their audience is what leaves so many activist academics open to the charge that they’re not as interested in changing minds as in signaling their superior virtue. Still, when it comes to Darwin himself, Fuentes is cursed in just the way we’d expect.

Fuentes and others engaged in similar projects don’t seem to grasp that racism wasn’t invented by scholars and scientists. Racism is the norm in cultures the world over. We have every reason to believe it crops up in most societies all on its own, based on people’s natural perceptions and the most intuitive understandings of group differences. Far from something that needs to be taught, it’s something we need to be taught to transcend. Many critics faulted another scientist, Steven Pinker, for not considering the history of racist colonialism in his case for recommitting to Enlightenment values, and indeed you can easily find quotes from the era’s philosophes that make us cringe today. But insisting that any program begun by racists will forever bear the stain of racism is like saying no species is truly terrestrial because all land-based life had its beginnings in the sea.

Isn’t it better to think of figures like Darwin and Dr. Seuss as akin to transitional species—like Tiktaalik—emerging from a morally less evolved era but containing within them the seeds of a more enlightened, more just society? Doesn’t that framework help to ease the frustration of people like Fuentes who see in Darwin’s writings a mosaic of promising lines of thought alongside the standard prejudices of his time? You could even go so far as to say that Darwin, despite never escaping a racist mindset himself, invented some of the cognitive tools that later generations used to overcome their own racial prejudices.

A glance at a historical timeline shows that while colonialism and slavery persisted for centuries under Christianity as the ascendent authority, when racism went scientific its days became numbered. That’s because the remedy for bad science is better science, and we’ve been getting more and more of that since before Galileo was placed on house arrest for challenging the church.

I don’t think for a second that I’m morally or intellectually superior to Fuentes; it’s entirely possible that two years from now I’ll have been persuaded he was right. The sanctimony and triteness suffusing his editorial notwithstanding, he comes across as likeable and genuinely fascinated with Darwin and the history of science. He’s also been admirably responsive to his critics on Twitter and elsewhere, a practice that sets him apart from many who argue in his vein. His expertise is impressive enough that I’d tune in to hear him discuss evolutionary psychology with Robert Wright anytime. But I think the curse of knowledge that leaves Fuentes so mystified about Darwin’s thinking about race extends to the very people he’d most like to convince today. The one advantage I have over Fuentes—I surmise—is that I have much more experience working and talking with people outside of academia, people who work with their hands and never went to college.

If you tell these people that race is a “social construct,” they’re going to think you’re being both contemptuous and dishonest—either that, or you’ve been indoctrinated to the point of delusion. You can see race with your own eyes, after all. And, sure, some cases are harder to classify, but the existence of El Caminos doesn’t invalidate the concepts of cars and trucks. Likewise, if you start going on about how racist Darwin was, or how Dr. Seuss’s drawings echo tropes from the days of Jim Crow, well, good luck keeping anyone’s attention. You have no chance, at any rate, of changing attitudes about race. What you’ll almost certainly accomplish though is a further widening of the already catastrophic cultural divide between the rural non-college-educated populations of our country and the urban elites who can’t help condescending to them.