READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

Campaigning Deities: Justifying the ways of Satan

Why do readers tend to admire Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost? It’s one of the instances where a nominally bad character garners more attention and sympathy than the good guy, a conundrum I researched through an evolutionary lens as part of my master’s thesis.

[Excerpt from Hierarchies in Hell and Leaderless Fight Clubs: Altruism, Narrative Interest, and the Adaptive Appeal of Bad Boys, my master’s thesis]

Milton believed Christianity more than worthy of a poetic canon in the tradition of the classical poets, and Paradise Lost represents his effort at establishing one. What his Christian epic has offered for many readers over the centuries, however, is an invitation to weigh the actions and motivations of immortals in mortal terms. In the story, God becomes a human king, albeit one with superhuman powers, while Satan becomes an upstart subject. As Milton attempts to “justify the ways of God to Man,” he is taking it upon himself simultaneously, and inadvertently, to justify the absolute dominion of a human dictator. One of the consequences of this shift in perspective is the transformation of a philosophical tradition devoted to parsing the logic of biblical teachings into something akin to a political campaign between two rival leaders, each laying out his respective platform alongside a case against his rival. What was hitherto recondite and academic becomes in Milton’s work immediate and visceral.

Keats famously penned the wonderfully self-proving postulate, “Axioms in philosophy are not axioms until they are proved upon our pulses,” which leaves open the question of how an axiom might be so proved. Milton’s God responds to Satan’s approach to Earth, and his foreknowledge of Satan’s success in tempting the original pair, with a preemptive defense of his preordained punishment of Man:

…Whose fault?

Whose but his own? Ingrate! He had of Me

All he could have. I made him just and right,

Sufficient to have stood though free to fall.

Such I created all th’ ethereal pow’rs

And spirits, both them who stood and who failed:

Freely they stood who stood and fell who fell.

Not free, what proof could they have giv’n sincere

Of true allegiance, constant faith or love

Where only what they needs must do appeared,

Not what they would? What praise could they receive?

What pleasure I from such obedience paid

When will and reason… had served necessity,

Not me? (3.96-111)

God is defending himself against the charge that his foreknowledge of the fall implies that Man’s decision to disobey was borne of something other than his free will. What choice could there have been if the outcome of Satan’s temptation was predetermined? If it wasn’t predetermined, how could God know what the outcome would be in advance? God’s answer—of course I granted humans free will because otherwise their obedience would mean nothing—only introduces further doubt. Now we must wonder why God cherishes Man’s obedience so fervently. Is God hungry for political power? If we conclude he is—and that conclusion seems eminently warranted—then we find ourselves on the side of Satan. It’s not so much God’s foreknowledge of Man’s fall that undermines human freedom; it’s God’s insistence on our obedience, under threat of God’s terrible punishment.

Milton faces a still greater challenge in his attempt to justify God’s ways “upon our pulses” when it comes to the fallout of Man’s original act of disobedience. The Son argues on behalf of Man, pointing out that the original sin was brought about through temptation. If God responds by turning against Man, then Satan wins. The Son thus argues that God must do something to thwart Satan: “Or shall the Adversary thus obtain/ His end and frustrate Thine?” (3.156-7). Before laying out his plan for Man’s redemption, God explains why punishment is necessary:

…Man disobeying

Disloyal breaks his fealty and sins

Against the high supremacy of Heav’n,

Affecting godhead, and so, losing all,

To expiate his treason hath naught left

But to destruction sacred and devote

He with his whole posterity must die. (3. 203-9)

The potential contradiction between foreknowledge and free choice may be abstruse enough for Milton’s character to convincingly discount: “If I foreknew/ Foreknowledge had no influence on their fault/ Which had no less proved certain unforeknown” (3.116-9). There is another contradiction, however, that Milton neglects to take on. If Man is “Sufficient to have stood though free to fall,” then God must justify his decision to punish the “whole posterity” as opposed to the individuals who choose to disobey. The Son agrees to redeem all of humanity for the offense committed by the original pair. His knowledge that every last human will disobey may not be logically incompatible with their freedom to choose; if every last human does disobey, however, the case for that freedom is severely undermined. The axiom of collective guilt precludes the axiom of freedom of choice both logically and upon our pulses.

In characterizing disobedience as a sin worthy of severe punishment—banishment from paradise, shame, toil, death—an offense he can generously expiate for Man by sacrificing the (his) Son, God seems to be justifying his dominion by pronouncing disobedience to him evil, allowing him to claim that Man’s evil made it necessary for him to suffer a profound loss, the death of his offspring. In place of a justification for his rule, then, God resorts to a simple guilt trip.

Man shall not quite be lost but saved who will,

Yet not of will in him but grace in me

Freely vouchsafed. Once more I will renew

His lapsed pow’rs though forfeit and enthralled

By sin to foul exorbitant desires.

Upheld by me, yet once more he shall stand

On even ground against his mortal foe,

By me upheld that he may know how frail

His fall’n condition is and to me owe

All his deliv’rance, and to none but me. (3.173-83)

Having decided to take on the burden of repairing the damage wrought by Man’s disobedience to him, God explains his plan:

Die he or justice must, unless for him

Some other as able and as willing pay

The rigid satisfaction, death for death. (3.210-3)

He then asks for a volunteer. In an echo of an earlier episode in the poem which has Satan asking for a volunteer to leave hell on a mission of exploration, there is a moment of hesitation before the Son offers himself up to die on Man’s behalf.

…On Me let thine anger fall.

Account Me Man. I for his sake will leave

Thy bosom and this glory next to Thee

Freely put off and for him lastly die

Well pleased. On Me let Death wreck all his rage! (3.37-42)

This great sacrifice, which is supposed to be the basis of the Son’s privileged status over the angels, is immediately undermined because he knows he won’t stay dead for long: “Yet that debt paid/ Thou wilt not leave me in the loathsome grave” (246-7). The Son will only die momentarily. This sacrifice doesn’t stack up well against the real risks and sacrifices made by Satan.

All the poetry about obedience and freedom and debt never takes on the central question Satan’s rebellion forces readers to ponder: Does God deserve our obedience? Or are the labels of good and evil applied arbitrarily? The original pair was forbidden from eating from the Tree of Knowledge—could they possibly have been right to contravene the interdiction? Since it is God being discussed, however, the assumption that his dominion requires no justification, that it is instead simply in the nature of things, might prevail among some readers, as it does for the angels who refuse to join Satan’s rebellion. The angels, after all, owe their very existence to God, as Abdiel insists to Satan. Who, then, are any of them to question his authority? This argument sets the stage for Satan’s remarkable rebuttal:

…Strange point and new!

Doctrine which we would know whence learnt: who saw

When this creation was? Remember’st thou

Thy making while the Maker gave thee being?

We know no time when we were not as now,

Know none before us, self-begot, self-raised

By our own quick’ning power…

Our puissance is our own. Our own right hand

Shall teach us highest deeds by proof to try

Who is our equal. (5.855-66)

Just as a pharaoh could claim credit for all the monuments and infrastructure he had commissioned the construction of, any king or dictator might try to convince his subjects that his deeds far exceed what he is truly capable of. If there’s no record and no witness—or if the records have been doctored and the witnesses silenced—the subjects have to take the king’s word for it.

That God’s dominion depends on some natural order, which he himself presumably put in place, makes his tendency to protect knowledge deeply suspicious. Even the angels ultimately have to take God’s claims to have created the universe and them along with it solely on faith. Because that same unquestioning faith is precisely what Satan and the readers of Paradise Lost are seeking a justification for, they could be forgiven for finding the answer tautological and unsatisfying. It is the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil that Adam and Eve are forbidden to eat fruit from. When Adam, after hearing Raphael’s recounting of the war in heaven, asks the angel how the earth was created, he does receive an answer, but only after a suspicious preamble:

…such commission from above

I have received to answer thy desire

Of knowledge with bounds. Beyond abstain

To ask nor let thine own inventions hope

Things not revealed which the invisible King

Only omniscient hath suppressed in night,

To none communicable in Earth or Heaven:

Enough is left besides to search and know. (7.118-125)

Raphael goes on to compare knowledge to food, suggesting that excessively indulging curiosity is unhealthy. This proscription of knowledge reminded Shelley of the Prometheus myth. It might remind modern readers of The Wizard of Oz—“Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain”—or to the space monkeys in Fight Club, who repeatedly remind us that “The first rule of Project Mayhem is, you do not ask questions.” It may also resonate with news about dictators in Asia or the Middle East trying to desperately to keep social media outlets from spreading word of their atrocities.

Like the protesters of the Arab Spring, Satan is putting himself at great risk by challenging God’s authority. If God’s dominion over Man and the angels is evidence not of his benevolence but of his supreme selfishness, then Satan’s rebellion becomes an attempt at altruistic punishment. The extrapolation from economic experiments like the ultimatum and dictator games to efforts to topple dictators may seem like a stretch, especially if humans are predisposed to forming and accepting positions in hierarchies, as a casual survey of virtually any modern organization suggests is the case.

Organized institutions, however, are a recent development in terms of human evolution. The English missionary Lucas Bridges wrote about his experiences with the Ona foragers in Tierra del Fuego in his 1948 book Uttermost Part of the Earth, and he expresses his amusement at his fellow outsiders’ befuddlement when they learn about the Ona’s political dynamics:

A certain scientist visited our part of the world and, in answer to his inquiries on this matter, I told him that the Ona had no chieftains, as we understand the word. Seeing that he did not believe me, I summoned Kankoat, who by that time spoke some Spanish. When the visitor repeated his question, Kankoat, too polite to answer in the negative, said: “Yes, senor, we, the Ona, have many chiefs. The men are all captains and all the women are sailors” (quoted in Boehm 62).

At least among Ona men, it seems there was no clear hierarchy. The anthropologist Richard Lee discovered a similar dynamic operating among the !Kung foragers of the Kalahari. In order to ensure that no one in the group can attain an elevated status which would allow him to dominate the others, several leveling mechanisms are in place. Lee quotes one of his informants:

When a young man kills much meat, he comes to think of himself as a chief or a big man, and he thinks of the rest of us as his servants or inferiors. We can’t accept this. We refuse one who boasts, for someday his pride will make him kill somebody. So we always speak of his meat as worthless. In this way we cool his heart and make him gentle. (quoted in Boehm 45)

These examples of egalitarianism among nomadic foragers are part of anthropologist Christopher Boehm’s survey of every known group of hunter-gatherers. His central finding is that “A distinctively egalitarian political style is highly predictable wherever people live in small, locally autonomous social and economic groups” (35-36). This finding bears on any discussion of human evolution and human nature because small groups like these constituted the whole of humanity for all but what amounts to the final instants of geological time.

Also read:

THE ADAPTIVE APPEAL OF BAD BOYS

SYMPATHIZING WITH PSYCHOS: WHY WE WANT TO SEE ALEX ESCAPE HIS FATE AS A CLOCKWORK ORANGE

Seduced by Satan

As long as the group they belong to is small enough for each group member to monitor the actions of the others, people can maintain strict egalitarianism, giving up whatever dominance they may desire for the assurance of not being dominated themselves. Satan very likely speaks to this natural ambivalence in humans. Benevolent leaders win our love and admiration through their selflessness and charisma. But no one wants to be a slave.

[Excerpt from Hierarchies in Hell and Leaderless Fight Clubs: Altruism, Narrative Interest, and the Adaptive Appeal of Bad Boys, my master’s thesis]

Why do we like the guys who seem not to care whether or not what they’re doing is right, but who often manage to do what’s right anyway? In the Star Wars series, Han Solo is introduced as a mercenary, concerned only with monetary reward. In the first episode of Mad Men, audiences see Don Draper saying to a woman that they should get married, and then in the final scene he arrives home to his actual wife. Tony Soprano, Jack Sparrow, Tom Sawyer, the list of male characters who flout rules and conventions, who lie, cheat and steal, but who nevertheless compel the attention, the favor, even the love of readers and moviegoers would be difficult to exhaust.

John Milton has been accused of both betraying his own and inspiring others' sympathy and admiration for what should be the most detestable character imaginable. When he has Satan, in Paradise Lost, say, “Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven,” many believed he was signaling his support of the king of England’s overthrow. Regicidal politics are well and good—at least from the remove of many generations—but voicing your opinions through such a disreputable mouthpiece? That’s difficult to defend. Imagine using a fictional Hitler to convey your stance on the current president.

Stanley Fish theorizes that Milton’s game was a much subtler one: he didn’t intend for Satan to be sympathetic so much as seductive, so that in being persuaded and won over to him readers would be falling prey to the same temptation that brought about the fall. As humans, all our hearts are marked with original sin. So if many readers of Milton’s magnum opus come away thinking Satan may have been in the right all along, the failure wasn’t the author’s unconstrained admiration for the rebel angel so much as it was his inability to adequately “justify the ways of God to men.” God’s ways may follow a certain logic, but the appeal of Satan’s ways is deeper, more primal.

In the “Argument,” or summary, prefacing Book Three, Milton relays some of God’s logic: “Man hath offended the majesty of God by aspiring to godhead and therefore, with all his progeny devoted to death, must die unless someone can be found sufficient to answer for his offence and undergo his punishment.” The Son volunteers. This reasoning has been justly characterized as “barking mad” by Richard Dawkins. But the lines give us an important insight into what Milton saw as the principle failing of the human race, their ambition to be godlike. It is this ambition which allows us to sympathize with Satan, who incited his fellow angels to rebellion against the rule of God.

In Book Five, we learn that what provoked Satan to rebellion was God’s arbitrary promotion of his own Son to a status higher than the angels: “by Decree/ Another now hath to himself ingross’t/ All Power, and us eclipst under the name/ Of King anointed.” Citing these lines, William Flesch explains, “Satan’s grandeur, even if it is the grandeur of archangel ruined, comes from his iconoclasm, from his desire for liberty.” At the same time, however, Flesch insists that, “Satan’s revolt is not against tyranny. It is against a tyrant whose place he wishes to usurp.” So, it’s not so much freedom from domination he wants, according to Flesch, as the power to dominate.

Anthropologist Christopher Boehm describes the political dynamics of nomadic peoples in his book Hierarchy in the Forest: TheEvolution of Egalitarian Behavior, and his descriptions suggest that parsing a motive of domination from one of preserving autonomy is much more complicated than Flesch’s analysis assumes. “In my opinion,” Boehm writes, “nomadic foragers are universally—and all but obsessively—concerned with being free from the authority of others” (68). As long as the group they belong to is small enough for each group member to monitor the actions of the others, people can maintain strict egalitarianism, giving up whatever dominance they may desire for the assurance of not being dominated themselves.

Satan very likely speaks to this natural ambivalence in humans. Benevolent leaders win our love and admiration through their selflessness and charisma. But no one wants to be a slave. Does Satan’s admirable resistance and defiance shade into narcissistic self-aggrandizement and an unchecked will to power? If so, is his tyranny any more savage than that of God? And might there even be something not altogether off-putting about a certain degree self-indulgent badness?

Also read:

CAMPAIGNING DEITIES: JUSTIFYING THE WAYS OF SATAN

THE ADAPTIVE APPEAL OF BAD BOYS

SYMPATHIZING WITH PSYCHOS: WHY WE WANT TO SEE ALEX ESCAPE HIS FATE AS A CLOCKWORK ORANGE

T.J. Eckleburg Sees Everything: The Great God-Gap in Gatsby part 2 of 2

The simple explanation for Fitzgerald’s decision not to gratify his readers but rather to disappoint and disturb them is that he wanted his novel to serve as an indictment of the types of behavior that are encouraged by the social conditions he describes in the story, conditions which would have been easily recognizable to many readers of his day and which persist into the Twenty-First Century.

Though The Great Gatsby does indeed tell a story of punishment, readers are left with severe doubts as to whether those who receive punishment actually deserve it. Gatsby is involved in criminal activities, and he has an affair with a married woman. Myrtle likewise is guilty of adultery. But does either deserve to die? What about George Wilson? His is the only attempt in the novel at altruistic punishment. So natural is his impulse toward revenge, however, and so given are readers to take that impulse for granted, that its function in preserving a broader norm of cooperation requires explanation. Flesch describes a series of experiments in the field of game theory centering on an exchange called the ultimatum game. One participant is given a sum of money and told he or she must propose a split with a second participant, with the proviso that if the second person rejects the cut neither will get to keep anything. Flesch points out, however, that

It is irrational for the responder not to accept any proposed split from the proposer. The responder will always come out better by accepting than by vetoing. And yet people generally veto offers of less than 25 percent of the original sum. This means they are paying to punish. They are giving up a sure gain in order to punish the selfishness of the proposer. (31)

To understand why George’s attempt at revenge is altruistic, consider that he had nothing to gain, from a purely selfish and rational perspective, and much to lose by killing the man he believed killed his wife. He was risking physical harm if a fight ensued. He was risking arrest for murder. Yet if he failed to seek revenge readers would likely see him as somehow less than human. His quest for justice, as futile and misguided as it is, would likely endear him to readers—if the discovery of how futile and misguided it was didn’t precede their knowledge of it taking place. Readers, in fact, would probably respond more favorably toward George than any other character in the story, including the narrator. But the author deliberately prevents this outcome from occurring.

The simple explanation for Fitzgerald’s decision not to gratify his readers but rather to disappoint and disturb them is that he wanted his novel to serve as an indictment of the types of behavior that are encouraged by the social conditions he describes in the story, conditions which would have been easily recognizable to many readers of his day and which persist into the Twenty-First Century. Though the narrator plays the role of second-order free-rider, the author clearly signals his own readiness to punish by publishing his narrative about such bad behavior perpetrated by characters belonging to a particular group of people, a group corresponding to one readers might encounter outside the realm of fiction.

Fitzgerald makes it obvious in the novel that beyond Tom’s simple contempt for George there exist several more severe impediments to what biologists would call group cohesion but that most readers would simply refer to as a sense of community. The idea of a community as a unified entity whose interests supersede those of the individuals who make it up is something biological anthropologists theorize religion evolved to encourage. In his book Darwin’s Cathedral, in which he attempts to explain religion in terms of group selection theory, David Sloan Wilson writes:

A group of people who abandon self-will and work tirelessly for a greater good will fare very well as a group, much better than if they all pursue their private utilities, as long as the greater good corresponds to the welfare of the group. And religions almost invariably do link the greater good to the welfare of the community of believers, whether an organized modern church or an ethnic group for whom religion is thoroughly intermixed with the rest of their culture. Since religion is such an ancient feature of our species, I have no problem whatsoever imagining the capacity for selflessness and longing to be part of something larger than ourselves as part of our genetic and cultural heritage. (175)

One of the main tasks religious beliefs evolved to handle would have been addressing the same “free-rider problem” William Flesch discovers at the heart of narrative. What religion offers beyond the social monitoring of group members is the presence of invisible beings whose concerns are tied to the collective concerns of the group.

Obviously, Tom Buchanan’s sense of community has clear demarcations. “Civilization is going to pieces,” he warns Nick as prelude to his recommendation of a book titled “The Rise of the Coloured Empires.” “The idea,” Tom explains, “is that if we don’t look out the white race will be—will be utterly submerged” (17). “We’ve got to beat them down,” Daisy helpfully, mockingly chimes in (18). While this animosity toward members of other races seems immoral at first glance, in the social context the Buchanans inhabit it actually represents a concern for the broader group, “the white race.” But Tom’s animosity isn’t limited to other races. What prompts Catherine to tell Nick how her sister “can’t stand” her husband during the gathering in Tom and Myrtle’s apartment is in fact Tom’s ridiculing of George. In response to another character’s suggestion that he’d like to take some photographs of people in Long Island “if I could get the entry,” Tom jokingly insists to Myrtle that she should introduce the man to her husband. Laughing at his own joke, Tom imagines a title for one of the photographs: “‘George B. Wilson at the Gasoline Pump,’ or something like that” (37). Disturbingly, Tom’s contempt for George based on his lowly social status has contaminated Myrtle as well. Asked by her sister why she married George in the first place, she responds, “I married him because I thought he was a gentleman…I thought he knew something about breeding but he wasn’t fit to lick my shoe” (39). Her sense of superiority, however, is based on the artificial plan for her and Tom to get married.

That Tom’s idea of who belongs to his own superior community is determined more by “breeding” than by economic success—i.e. by birth and not accomplishment—is evidenced by his attitude toward Gatsby. In a scene that has Tom stopping with two friends, a husband and wife, at Gatsby’s mansion while riding horses, he is shocked when Gatsby shows an inclination to accept an invitation to supper extended by the woman, who is quite drunk. Both the husband and Tom show their disapproval. “My God,” Tom says to Nick, “I believe the man’s coming…Doesn’t he know she doesn’t want him?” (109). When Nick points out that woman just said she did want him, Tom answers, “he won’t know a soul there.” Gatsby’s statement in the same scene that he knows Tom’s wife provokes him, as soon as Gatsby has left the room, to say, “By God, I may be old-fashioned in my ideas but women run around too much these days to suit me. They meet all kinds of crazy fish” (110). In a later scene that has Tom accompanying Daisy, with Nick in tow, to one of Gatsby’s parties, he asks, “Who is this Gatsby anyhow?... Some big bootlegger?” When Nick says he’s not, Tom says, “Well, he certainly must have strained himself to get this menagerie together” (114). Even when Tom discovers that Gatsby and Daisy are having an affair, he still doesn’t take Gatsby seriously. He calls Gatsby “Mr. Nobody from Nowhere” (137), and says, “I’ll be damned if I see how you got within a mile of her unless you brought the groceries to the back door” (138). Once he’s succeeded in scaring Daisy with suggestions of Gatsby’s criminal endeavors, Tom insists the two drive home together, saying, “I think he realizes that his presumptuous little flirtation is over” (142).

When George Wilson looks to the eyes of Dr. Eckleburg in supplication after that very car ride leads to Myrtle’s death, the fact that this “God” is an advertisement, a supplication in its own right to viewers on behalf of the optometrist to boost his business, symbolically implicates the substitution of markets for religion—or a sense of common interest—as the main factor behind Tom’s superciliously careless sense of privilege. The eyes seem such a natural stand-in for an absent God that it’s easy to take the symbolic logic for granted without wondering why George might mistake them as belonging to some sentient agent. Evolutionary psychologist Jesse Bering takes on that very question in The God Instinct: The Psychology of Souls, Destiny, and the Meaning of Life, where he cites research suggesting that “attributing moral responsibility to God is a sort of residual spillover from our everyday social psychology dealing with other people” (138). Bering theorizes that humans’ tendency to assume agency behind even random physical events evolved as a by-product of our profound need to understand the motives and intentions of our fellow humans: “When the emotional climate is just right, there’s hardly a shape or form that ‘evidence’ cannot assume. Our minds make meaning by disambiguating the meaningless” (99). In place of meaningless events, humans see intentional signs.

According to Bering’s theory, George Wilson’s intense suffering would have made him desperate for some type of answer to the question of why such tragedy has befallen him. After discussing research showing that suffering, as defined by societal ills like infant mortality and violent crime, and “belief in God were highly correlated,” Bering suggests that thinking of hardship as purposeful, rather than random, helps people cope because it allows them to place what they’re going through in the context of some larger design (139). What he calls “the universal common denominator” to all the permutations of religious signs, omens, and symbols, is the same cognitive mechanism, “theory of mind,” that allows humans to understand each other and communicate so effectively as groups. “In analyzing things this way,” Bering writes,

we’re trying to get into God’s head—or the head of whichever culturally constructed supernatural agent we have on offer… This is to say, just like other people’s surface behaviors, natural events can be perceived by us human beings as being about something other than their surface characteristics only because our brains are equipped with the specialized cognitive software, theory of mind, that enables us to think about underlying psychological causes. (79)

So George, in his bereaved and enraged state, looks at a billboard of a pair of eyes and can’t help imagining a mind operating behind them, one whose identity he’s learned to associate with a figure whose main preoccupation is the judgment of individual humans’ moral standings. According to both David Sloan Wilson and Jesse Bering, though, the deity’s obsession with moral behavior is no coincidence.

Covering some of the same game theory territory as Flesch, Bering points out that the most immediate purpose to which we put our theory of mind capabilities is to figure out how altruistic or selfish the people around us are. He explains that

in general, morality is a matter of putting the group’s needs ahead of one’s own selfish interests. So when we hear about someone who has done the opposite, especially when it comes at another person’s obvious expense, this individual becomes marred by our social judgment and grist for the gossip mills. (183)

Having arisen as a by-product of our need to monitor and understand the motives of other humans, religion would have been quickly co-opted in the service of solving the same free-rider problem Flesch finds at the heart of narratives. Alongside our concern for the reputations of others is a close guarding of our own reputations. Since humans are given to assuming agency is involved even in random events like shifts in weather, group cohesion could easily have been optimized with the subtlest suggestion that hidden agents engage in the same type of monitoring as other, fully human members of the group. Bering writes:

For many, God represents that ineradicable sense of being watched that so often flares up in moments of temptation—He who knows what’s in our hearts, that private audience that wants us to act in certain ways at critical decision-making points and that will be disappointed in us otherwise. (191)

Bering describes some of his own research that demonstrates this point. Coincident with the average age at which children begin to develop a theory of mind (around 4), they began responding to suggestions that they’re being watched by an invisible agent—named Princess Alice in honor of Bering’s mother—by more frequently resisting the temptation to avail themselves of opportunities to cheat that were built into the experimental design of a game they were asked to play (Piazza et al. 311-20). An experiment with adult participants, this time told that the ghost of a dead graduate student had been seen in the lab, showed the same results; when competing in a game for fifty dollars, they were much less likely to cheat than others who weren’t told the ghost story (Bering 193).

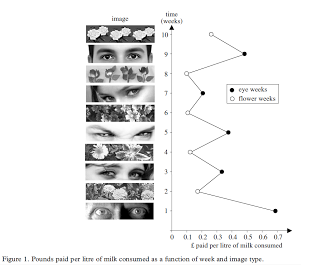

Bering also cites a study that has even more immediate relevance to George Wilson’s odd behavior vis-à-vis Dr. Eckleburg’s eyes. In “Cues of Being Watched Enhance Cooperation in a Real-World Setting,” the authors describe an experiment in which they tested the effects of various pictures placed near an “honesty box,” where people were supposed to be contributing money in exchange for milk and tea. What they found is that when the pictures featured human eyes more people contributed more money than when they featured abstract patterns of flowers. They theorize that

images of eyes motivate cooperative behavior because they induce a perception in participants of being watched. Although participants were not actually observed in either of our experimental conditions, the human perceptual system contains neurons that respond selectively to stimuli involving faces and eyes…, and it is therefore possible that the images exerted an automatic and unconscious effect on the participants’ perception that they were being watched. Our results therefore support the hypothesis that reputational concerns may be extremely powerful in motivating cooperative behavior. (2) (But also see Sparks et al. for failed replications)

This study also suggests that, while Fitzgerald may have meant the Dr. Eckleburg sign as a nod toward religion being supplanted by commerce, there is an alternate reading of the scene that focuses on the sign’s more direct impact on George Wilson. In several scenes throughout the novel, Wilson shows his willingness to acquiesce in the face of Tom’s bullying. Nick describes him as “spiritless” and “anemic” (29). It could be that when he says “God sees everything” he’s in fact addressing himself because he is tempted not to pursue justice—to let the crime go unpunished and thus be guilty himself of being a second-order free-rider. He doesn’t, after all, exert any great effort to find and kill Gatsby, and he kills himself immediately thereafter anyway.

Religion in Gatsby does, of course, go beyond some suggestive references to an empty placeholder. Nick ends the story with a reflection on how “Gatsby believed in the green light,” the light across the bay which he knew signaled Daisy’s presence in the mansion she lived in there. But for Gatsby it was also “the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther… And one fine morning—” (189). Earlier Nick had explained how Gatsby “talked a lot about the past and I gathered that he wanted to recover something, some idea of himself perhaps, that had gone into loving Daisy.” What that idea was becomes apparent in the scene describing Gatsby and Daisy’s first kiss, which occurred years prior to the events of the plot. “He knew that when he kissed this girl, and forever wed his unutterable visions to her perishable breath, his mind would never romp again like the mind of God… At his lips’ touch she blossomed for him like a flower and the incarnation was complete” (117). In place of some mind in the sky, the design Americans are encouraged to live by is one they have created for themselves. Unfortunately, just as there is no mind behind the eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg, the designs many people come up with for themselves are based on tragically faulty premises.

The replacement of religiously inspired moral principles with selfish economic and hierarchical calculations, which Dr. Eckleburg so perfectly represents, is what ultimately leads to all the disgraceful behavior Nick describes. He writes, “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and people and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess” (188). Game theorist and behavioral economist Robert Frank, whose earlier work greatly influenced William Flesch’s theories of narrative, has recently written about how the same social dynamics Fitzgerald lamented are in place again today. In The Darwin Economy, he describes what he calls an “expenditure cascade”:

The explosive growth of CEO pay in recent decades, for example, has led many executives to build larger and larger mansions. But those mansions have long since passed the point at which greater absolute size yields additional utility… Top earners build bigger mansions simply because they have more money. The middle class shows little evidence of being offended by that. On the contrary, many seem drawn to photo essays and TV programs about the lifestyles of the rich and famous. But the larger mansions of the rich shift the frame of reference that defines acceptable housing for the near-rich, who travel in many of the same social circles… So the near-rich build bigger, too, and that shifts the relevant framework for others just below them, and so on, all the way down the income scale. By 2007, the median new single-family house built in the United States had an area of more than 2,300 square feet, some 50 percent more than its counterpart from 1970. (61-2)

How exactly people are straining themselves to afford these houses would be a fascinating topic for Fitzgerald’s successors. But one thing is already abundantly clear: it’s not the CEOs who are cleaning up the mess.

Also read:

HOW TO GET KIDS TO READ LITERATURE WITHOUT MAKING THEM HATE IT

WHY THE CRITICS ARE GETTING LUHRMANN'S GREAT GATSBY SO WRONG

WHY SHAKESPEARE NAUSEATED DARWIN: A REVIEW OF KEITH OATLEY'S "SUCH STUFF AS DREAMS"

T.J. Eckleburg Sees Everything: The Great God-Gap in Gatsby part 1 of 2

So profound is humans’ concern for their reputations that they can even be nudged toward altruistic behaviors by the mere suggestion of invisible witnesses or the simplest representation of watching eyes. The billboard featuring Dr. Eckleburg’s eyes, however, holds no sway over George’s wife Myrtle, or the man she has an affair with. That this man, Tom Buchanan, has such little concern for his reputation—or that he simply feels entitled to exploit Myrtle—serves as an indictment of the social and economic inequality in the America of Fitzgerald’s day.

When George Wilson, in one of the most disturbing scenes in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic The Great Gatsby, tells his neighbor that “God sees everything” while staring disconsolately at the weathered advertisement of some long-ago optometrist named T.J. Eckleburg, his longing for a transcendent authority who will mete out justice on his behalf pulls at the hearts of readers who realize his plea will go unheard. Anthropologists and psychologists studying the human capacity for cooperation and altruism are coming to view religion as an important factor in our evolution. Since the cooperative are always at risk of being exploited by the selfish, mechanisms to enforce altruism had to be in place for any tendency to behave for the benefit of others to evolve. The most basic of these mechanisms is a constant awareness of our own and our neighbors’ reputations. Humans, research has shown, are far more tempted to behave selfishly when they believe it won’t harm their reputations—i.e. when they believe no witnesses are present.

So profound is humans’ concern for their reputations that they can even be nudged toward altruistic behaviors by the mere suggestion of invisible witnesses or the simplest representation of watching eyes. The billboard featuring Dr. Eckleburg’s eyes, however, holds no sway over George’s wife Myrtle, or the man she has an affair with. That this man, Tom Buchanan, has such little concern for his reputation—or that he simply feels entitled to exploit Myrtle—serves as an indictment of the social and economic inequality in the America of Fitzgerald’s day, which carved society into hierarchically arranged echelons and exposed the have-nots to the careless depredations of the haves.

Nick Carraway, the narrator, begins the story by recounting a lesson he learned from his father as part of his Midwestern upbringing. “Whenever you feel like criticizing anyone,” Nick’s father had told him, “just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had”(5). This piece of wisdom serves at least two purposes: it explains Nick’s self-proclaimed inclination to “reserve all judgments,” highlighting the severity of the wrongdoings which have prompted him to write the story; and it provides an ironic moral lens through which readers view the events of the plot. What is to be made, in light of Nick’s father’s reminder about unevenly parceled out advantages, of the crimes committed by wealthy characters like Tom and Daisy Buchanan?

The focus on morality notwithstanding, religion plays a scant, but surprising, role in The Great Gatsby. It first appears in a conversation between Nick and Catherine, the sister of Myrtle Wilson. Catherine explains to Nick that neither Tom nor Myrtle “can stand the person they’re married to” (37). To the obvious question of why they don’t simply leave their spouses, Catherine responds that it’s Daisy, Tom’s wife, who represents the sole obstacle to the lovers’ happiness. “She’s a Catholic,” Catherine says, “and they don’t believe in divorce” (38). However, Nick explains that “Daisy was not a Catholic,” and he goes on to admit, “I was a little shocked by the elaborateness of the lie.” The conversation takes place at a small gathering hosted by Tom and Myrtle in an apartment rented, it seems, for the sole purpose of giving the two a place to meet. Before Nick leaves the party, he witnesses an argument between the hosts over whether Myrtle has any right to utter Daisy’s name which culminates in Tom striking her and breaking her nose. Obviously, Tom doesn’t despise his wife as much as Myrtle does her husband. And the lie about Daisy’s religious compunctions serves simply to justify Tom’s refusal to leave her and facilitate his continued exploitation of Myrtle.

The only other scene in which a religious belief is asserted explicitly is the one featuring the conversation between George and his neighbor. It comes after Myrtle, whose dalliance had finally aroused her husband’s suspicion, has been struck by a car and killed. George, upon discovering that something had been going on behind his back, locked Myrtle in his garage, and it was when she escaped and ran out into the road to stop the car she thought Tom was driving that she got hit. As the dust from the accident settles—literally, since the garage and the stretch of road are situated in a “valley of ashes” created by the remnants of the coal powering the nearby city being dumped alongside the adjacent rail tracks—George is left alone with a fellow inhabitant of the valley, a man named Michaelis, who asks if he belongs to a church where there might a be a priest he can call to come comfort him. “Don’t belong to one,” George answers (165). He does, however, describe a religious belief of sorts to Michaelis. Having explained why he’d begun to suspect Myrtle was having an affair, George goes on to say, “I told her she might fool me but she couldn’t fool God. I took her to the window.” He walks to the window again as he’s telling the story to his neighbor. “I said, ‘God knows what you’ve been doing, everything you’ve been doing. You may fool me but you can’t fool God!’” (167). Michaelis, who is by now fearing for George’s sanity, notices something disturbing as he stands listening to this rant: “Standing behind him Michaelis saw with a shock that he was looking at the eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg which had just emerged pale and enormous from the dissolving night” (167). When George speaks again, repeating, “God sees everything,” Michaelis feels compelled to assure him, “That’s an advertisement” (167). Though when George first expresses the sentiment, part declaration, part plea, he was clearly thinking of Myrtle’s crime against him, when he repeats it he seems to be thinking of the driver’s crime against Myrtle. God may have seen it, but George takes it upon himself to deliver the punishment.

George Wilson’s turning to God for some moral accounting, despite his general lack of religious devotion, mirrors Nick Carraway’s efforts to settle the question of culpability, despite his own professed reluctance to judge, through the telling of this tragic story. Nick learns from Gatsby that it was in fact Daisy, with whom Gatsby has been carrying on an affair, who was behind the wheel of the car that killed Myrtle. But Gatsby, who was in the passenger seat, assures him it was an accident, not revenge for the affair Myrtle was carrying on with Daisy’s husband. Yet when George finally leaves his garage and turns to Tom to find out who owns the car that killed his wife, assuming it is the same man his wife was cheating on him with, Tom informs him the car belongs to Gatsby, leaving out the crucial fact that Gatsby never met Myrtle. George goes to Gatsby’s mansion, finds him in his pool, shoots and kills him, and then turns the gun on himself. Three people end up dead, Myrtle, George, and Gatsby. Despite their clear complicity, though, Tom and Daisy experience nary a repercussion beyond the natural grief of losing their lovers. Insofar as Nick believes the Buchanans’ perfect getaway is an intolerable injustice, he must realize he holds the power to implicate them, to damage their reputations, by writing and publishing his account of the incidents leading up to the deaths.

Evolutionary critic William Flesch sees our human passion for narrative as a manifestation of our obsession with our own and our fellow humans’ reputations, which evolved at least in part to keep track of each other’s propensities for moral behavior. In Comeuppance: Costly Signaling, Altruistic Punishment, and Other Biological Components of Fiction, Flesch lays out his attempt at solving what he calls “the puzzle of narrative interest,” by which he means the question of why people feel “anxiety on behalf of and about the motives, actions, and experiences of fictional characters” (7). He finds the key to solving this puzzle in a concept called “strong reciprocity,” whereby “the strong reciprocator punishes and rewards others for their behavior toward any member of the social group, and not just or primarily for their individual interactions with the reciprocator” (22). An example of this phenomenon takes place in the novel when the guests at Gatsby’s parties gossip and ardently debate about which of the rumors circling their host are true—particularly of interest is the one saying that “he killed a man” (48). Flesch cites reports from experiments demonstrating that in uneven exchanges, participants with no stake in the outcome are actually willing to incur some cost to themselves in an effort to enforce fairness (31-5). He then goes on to give a compelling account of how this tendency goes a long way toward an explanation of our human fascination with storytelling.

Flesch’s theory of narrative interest begins with models of the evolution of cooperation. For the first groups of human ancestors to evolve cooperative or altruistic traits, they would have had to solve what biologists and game theorists call “the free-rider problem.” Flesch explains:

Darwin himself had proposed a way for altruism to evolve through a mechanism of group selection. Groups with altruists do better as a group than groups without. But it was shown in the 1960s that, in fact, such groups would be too easily infiltrated or invaded by nonaltruists—that is, that group boundaries were too porous—to make group selection strong enough to overcome competition at the level of the individual or the gene. (5)

Strong, or indirect reciprocity, coupled with a selfish concern for one’s own reputation, may have evolved as mechanisms to address this threat of exploitative non-cooperators. For instance, in order for Tom Buchanan to behave selfishly by sleeping with George Wilson’s wife, he had to calculate his chances of being discovered in the act and punished. Interestingly, after “exchanging a frown with Doctor Eckleburg” while speaking to Nick in an early scene in Wilson’s garage, Tom suggests his motives for stealing away with Myrtle are at least somewhat noble. “Terrible place,” he says of the garage and the valley of ashes. “It does her good to get away” (30). Nick, clearly uncomfortable with the position Tom has put him in, where he has to choose whether to object to Tom’s behavior or play the role of second-order free-rider himself, poses the obvious question: “Doesn’t her husband object?” To which Tom replies, “He’s so dumb he doesn’t know he’s alive” (30). Nick, inclined to reserve judgment, keeps Tom and Myrtle’s secret. Later in the novel, though, he keeps the same secret for Daisy and Gatsby.

What makes Flesch’s theory so compelling is that it sheds light on the roles played by everyone from the author, in this case Fitzgerald, to the readers, to the characters, whose nonexistence beyond the pages of the novel is little obstacle to their ability to arouse sympathy or ire. Just as humans are keen to ascertain the relative altruism of their neighbors, so too are they given to broadcasting signals of their own altruism. Flesch explains, “we track not only the original actor whose actions we wish to see reciprocated, whether through reward or more likely punishment; we track as well those who are in a position to track that actor, and we track as well those in a position to track those tracking the actor” (50). What this means is that even if the original “actor” is fictional, readers can signal their own altruism by becoming emotionally engaged in the outcome of the story, specifically by wanting to see altruistic characters rewarded and selfish characters punished.

Nick Carraway is tracking Tom Buchanan’s actions, for instance. Reading the novel, we have little doubt what Nick’s attitude toward Tom is, especially as the story progresses. Though we may favor Nick over Tom, Nick’s failure to sufficiently punish Tom when the degree of his selfishness first becomes apparent tempers any positive feelings we may have toward him. As Flesch points out, “altruism could not sustain an evolutionarily stable system without the contribution of altruistic punishers to punish the free-riders who would flourish in a population of purely benevolent altruists” (66).

On the other hand, through the very act of telling the story, the narrator may be attempting to rectify his earlier moral complacence. According to Flesch’s model of the dynamics of fiction, “The story tells a story of punishment; the story punishes as story; the storyteller represents him- or herself as an altruistic punisher by telling it” (83). However, many readers of Gatsby probably find Nick’s belated punishment insufficient, and if they fail to see the novel as a comment on the real injustice Fitzgerald saw going on around him they would be both confused and disappointed by the way the story ends.

I am Jack’s Raging Insomnia: The Tragically Overlooked Moral Dilemma at the Heart of Fight Club

There’s a lot of weird theorizing about what the movie Fight Club is really about and why so many men find it appealing. The answer is actually pretty simple: the narrator can’t sleep because his job has him doing something he knows is wrong, but he’s so emasculated by his consumerist obsessions that he won’t risk confronting his boss and losing his job. He needs someone to teach him to man up, so he creates Tyler Durden. Then Tyler gets out of control.

Image by Canva’s Magic Media

[This essay is a brief distillation of ideas explored in much greater depth in Hierarchies in Hell and Leaderless Fight Clubs: Altruism, Narrative Interest, and the Adaptive Appeal of Bad Boys, my master’s thesis]

If you were to ask one of the millions of guys who love the movie Fight Club what the story is about, his answer would most likely emphasize the violence. He might say something like, “It’s about men returning to their primal nature and getting carried away when they find out how good it feels.” Actually, this is an answer I would expect from a guy with exceptional insight. A majority would probably just say it’s about a bunch of guys who get together to beat the crap out of each other and pull a bunch pranks. Some might remember all the talk about IKEA and other consumerist products. Our insightful guy may even connect the dots and explain that consumerism somehow made the characters in the movie feel emasculated, and so they had to resort to fighting and vandalism to reassert their manhood. But, aside from ensuring they would know what a duvet is—“It’s a fucking blanket”—what is it exactly about shopping for household décor and modern conveniences that makes men less manly?

Maybe Fight Club is just supposed to be fun, with all the violence, and the weird sex scene with Marla, and all the crazy mischief the guys get into, but also with a few interesting monologues and voiceovers to hint at deeper meanings. And of course there’s Tyler Durden—fearless, clever, charismatic, and did you see those shredded abs? Not only does he not take shit from anyone, he gets a whole army to follow his lead, loyal to the death. On the other hand, there’s no shortage of characters like this in movies, and if that’s all men liked about Fight Club they wouldn’t sit through all the plane flights, support groups, and soap-making. It just may be that, despite the rarity of fans who can articulate what they are, the movie actually does have profound and important resonances.

If you recall, the Edward Norton character, whom I’ll call Jack (following the convention of the script), decides that his story should begin with the advent of his insomnia. He goes to the doctor but is told nothing is wrong with him. His first night’s sleep comes only after he goes to a support group and meets Bob, he of the “bitch tits,” and cries a smiley face onto his t-shirt. But along comes Marla who like Jack is visiting support groups but is not in fact recovering, sick, or dying. She is another tourist. As long as she's around, he can’t cry, and so he can’t sleep. Soon after Jack and Marla make a deal to divide the group meetings and avoid each other, Tyler Durden shows up and we’re on our way to Fight Clubs and Project Mayhem. Now, why the hell would we accept these bizarre premises and continue watching the movie unless at some level Jack’s difficulties, as well as their solutions, make sense to us?

So why exactly was it that Jack couldn’t sleep at night? The simple answer, the one that Tyler gives later in the movie, is that he’s unhappy with his life. He hates his job. Something about his “filing cabinet” apartment rankles him. And he’s alone. Jack’s job is to fly all over the country to investigate accidents involving his company’s vehicles and to apply “the formula.” I’m going to quote from Chuck Palahniuk’s book:

You take the population of vehicles in the field (A) and multiply it by the probable rate of failure (B), then multiply the result by the average cost of an out-of-court settlement (C).

A times B times C equals X. This is what it will cost if we don’t initiate a recall.

If X is greater than the cost of a recall, we recall the cars and no one gets hurt.

If X is less than the cost of a recall, then we don’t recall (30).

Palahniuk's inspiration for Jack's job was an actual case involving the Ford Pinto. What this means is that Jack goes around trying to protect his company's bottom line to the detriment of people who drive his company's cars. You can imagine the husband or wife or child or parent of one of these accident victims hearing about this job and asking Jack, "How do you sleep at night?"

Going to support groups makes life seem pointless, short, and horrible. Ultimately, we all have little control over our fates, so there's no good reason to take responsibility for anything. When Jack burst into tears as Bob pulls his face into his enlarged breasts, he's relinquishing all accountability; he's, in a sense, becoming a child again. Accordingly, he's able to sleep like a baby. When Marla shows up, not only is he forced to confront the fact that he's healthy and perfectly able to behave responsibly, but he is also provided with an incentive to grow up because, as his fatuous grin informs us, he likes her. And, even though the support groups eventually fail to assuage his guilt, they do inspire him with the idea of hitting bottom, losing all control, losing all hope.

Here’s the crucial point: If Jack didn't have to worry about losing his apartment, or losing all his IKEA products, or losing his job, or falling out of favor with his boss, well, then he would be free to confront that same boss and tell him what he really thinks of the operation that has supported and enriched them both. Enter Tyler Durden, who systematically turns all these conditionals into realities. In game theory terms, Jack is both a 1st order and a 2nd order free rider because he both gains at the expense of others and knowingly allows others to gain in the same way. He carries on like this because he's more motivated by comfort and safety than he is by any assurance that he's doing right by other people.

This is where Jack being of "a generation of men raised by women" becomes important (50). Fathers and mothers tend to treat children differently. A study that functions well symbolically in this context examined the ways moms and dads tend to hold their babies in pools. Moms hold them facing themselves. Dads hold them facing away. Think of the way Bob's embrace of Jack changes between the support group and the fight club. When picked up by moms, babies breathing and heart-rates slow. Just the opposite happens when dads pick them up--they get excited. And if you inventory the types of interactions that go on between the two parents it's easy to see why.

Not only do dads engage children in more rough-and-tumble play; they are also far more likely to encourage children to take risks. In one study, fathers told they'd have to observe their child climbing a slope from a distance making any kind of rescue impossible in the event of a fall set the slopes at a much steeper angle than mothers in the same setup.

Fight Club isn't about dominance or triumphalism or white males' reaction to losing control; it's about men learning that they can't really live if they're always playing it safe. Jack actually says at one point that winning or losing doesn't much matter. Indeed, one of the homework assignments Tyler gives everyone is to start a fight and lose. The point is to be willing to risk a fight when it's necessary--i.e. when someone attempts to exploit or seduce you based on the assumption that you'll always act according to your rational self-interest.

And the disturbing truth is that we are all lulled into hypocrisy and moral complacency by the allures of consumerism. We may not be "recall campaign coordinators" like Jack. But do we know or care where our food comes from? Do we know or care how our soap is made? Do we bother to ask why Disney movies are so devoid of the gross mechanics of life? We would do just about anything for comfort and safety. And that is precisely how material goods and material security have emasculated us. It's easy to imagine Jack's mother soothing him to sleep some night, saying, "Now, the best thing to do, dear, is to sit down and talk this out with your boss."

There are two scenes in Fight Club that I can't think of any other word to describe but sublime. The first is when Jack finally confronts his boss, threatening to expose the company's practices if he is not allowed to leave with full salary. At first, his boss reasons that Jack's threat is not credible, because bringing his crimes to light would hurt Jack just as much. But the key element to what game theorists call altruistic punishment is that the punisher is willing to incur risks or costs to mete out justice. Jack, having been well-fathered, as it were, by Tyler, proceeds to engage in costly signaling of his willingness to harm himself by beating himself up, literally. In game theory terms, he's being rationally irrational, making his threat credible by demonstrating he can't be counted on to pursue his own rational self-interest. The money he gets through this maneuver goes, of course, not into anything for Jack, but into Fight Club and Project Mayhem.

The second sublime scene, and for me the best in the movie, is the one in which Jack is himself punished for his complicity in the crimes of his company. How can a guy with stitches in his face and broken teeth, a guy with a chemical burn on his hand, be punished? Fittingly, he lets Tyler get them both in a car accident. At this point, Jack is in control of his life, he's no longer emasculated. And Tyler flees.

One of the confusing things about the movie is that it has two overlapping plots. The first, which I've been exploring up to this point, centers on Jack's struggle to man up and become an altruistic punisher. The second is about the danger of violent reactions to the murder machine of consumerism. The male ethic of justice through violence can all too easily morph into fascism. And so, once Jack has created this father figure and been initiated into manhood by him, he then has to reign him in--specifically, he has to keep him from killing Marla. This second plot entails what anthropologist Christopher Boehm calls a "domination episode," in which an otherwise egalitarian group gets taken over by a despot who must then be defeated. Interestingly, only Jack knows for sure how much authority Tyler has, because Tyler seemingly undermines that authority by giving contradictory orders. But by now Jack is well schooled on how to beat Tyler--pretty much the same way he beat his boss.

It's interesting to think about possible parallels between the way Fight Club ends and what happened a couple years later on 9/11. The violent reaction to the criminal excesses of consumerism and capitalism wasn't, as it actually occurred, homegrown. And it wasn't inspired by any primal notion of manhood but by religious fanaticism. Still, in the minds of the terrorists, the attacks were certainly a punishment, and there's no denying the cost to the punishers.

Also read:

WHAT MAKES "WOLF HALL" SO GREAT?

Bad Men

There’s a lot not to like about the AMC series Mad Men, but somehow I found the show riveting despite all of its myriad shortcomings. Critic Daniel Mendelsohn offered up a theory to explain the show’s appeal, that it simply inspires nostalgia for all our lost childhoods. As intriguing as I always find Mendelsohn’s writing, though, I don’t think his theory holds up.

Though I had mixed feelings about the first season of Mad Men, which I picked up at Half Price Books for a steal, I still found enormous appeal in the more drawn out experience of the series unfolding. Movies lately have been leaving me tragically unmoved, with those in the action category being far too noisy and preposterous and those in the drama one too brief to establish any significant emotional investment in the characters. In a series, though, especially those in the new style pioneered by The Sopranos which eschew efforts to wrap up their plots by the end of each episode, viewers get a chance to follow characters as they develop, and the resultant investment in them makes even the most underplayed and realistic violence among them excruciatingly riveting. So, even though I found Pete Campbell, an account executive at the ad agency Sterling Cooper, the main setting for Mad Men, annoying instead of despicable, and the treatment of what we would today call sexual harassment in the office crude, self-congratulatory, and overdone, by the time I had finished watching the first season I was eager to get my hands on the second. I’ve now seen the first four seasons.

Reading up on the show on Wikipedia, I came across a few quotes from Daniel Mendelsohn’s screed against the series, “The Mad Men Account” in the New York Review of Books, and since Mendelsohn is always fascinating even when you disagree with him I made a point of reading his review after I’d finished the fourth season. His response was similar to mine in that he found himself engrossed in the show despite himself. There’s so much hoopla. But there’s so much wrong with the show. Allow me a longish quote:

The writing is extremely weak, the plotting haphazard and often preposterous, the characterizations shallow and sometimes incoherent; its attitude toward the past is glib and its self-positioning in the present is unattractively smug; the acting is, almost without exception, bland and sometimes amateurish.

Worst of all—in a drama with aspirations to treating social and historical ‘issues’—the show is melodramatic rather than dramatic. By this I mean that it proceeds, for the most part, like a soap opera, serially (and often unbelievably) generating, and then resolving, successive personal crises (adulteries, abortions, premarital pregnancies, interracial affairs, alcoholism and drug addiction, etc.), rather than exploring, by means of believable conflicts between personality and situation, the contemporary social and cultural phenomena it regards with such fascination: sexism, misogyny, social hypocrisy, racism, the counterculture, and so forth.

I have to say Mendelsohn is right on the mark here—though I will take issue with his categorical claims about the acting—leaving us with the question of why so many of us, me and Mendelsohn included, find the show so fascinating. Reading the review I found myself wanting to applaud at several points as it captures so precisely, and even artistically, the show’s failings. And yet these failings seem to me mild annoyances marring the otherwise profound gratification I get from watching. Mendelsohn lights on an answer for how it can be good while being so bad, one that squares the circle by turning the shortcomings into strengths.

If the characters are bland, stereotypical sixties people instead of individuals, if the issues are advertised rather than dramatized, if everyone depicted is hopelessly venal while evincing a smug, smiling commitment to decorum, well it’s because the show’s creator, Matthew Weiner, was born in 1965, and he’s trying to recreate the world of his parents. Mendelsohn quotes Weiner:

part of the show is trying to figure out—this sounds really ineloquent—trying to figure out what is the deal with my parents. Am I them? Because you know you are…. The truth is it’s such a trope to sit around and bash your parents. I don’t want it to be like that. They are my inspiration, let’s not pretend.

Mendelsohn’s clever solution to the Mad Men puzzle is that its appeal derives from its child’s-eye view of the period during which its enthusiasts’ parents were in their ascendancy. The characters aren’t deep because children wouldn’t have the wherewithal to appreciate their depth. The issues aren’t explored in all their complexity because children are only ever vaguely aware of them. For Mendelsohn, the most important characters are the Drapers’ daughter, Sally, and the neighbor kid, Glen, who first has a crush on Don’s wife, Betty, and then falls for Sally herself. And it turns out Glen is played by Weiner’s own son.

I admit the episodes that portrayed the Draper’s divorce struck me as poignant to the point of being slightly painful, resonating as they did with my memories of my own parents’ divorce. But that was in the ‘80’s not the 60’s. And Glen is, at least for me, one of the show’s annoyances, not by any means its main appeal. His long, unblinking stares at Betty, which Mendelsohn sees as so fraught with meaning, I can’t help finding creepy. The kid makes my skin crawl, much the way Pete Campbell does. I’m forced to consider that Mendelsohn, as astute as he is about a lot of the scenes and characters, is missing something, or getting something really wrong.

In trying to account for the show’s overwhelming appeal, I think Mendelsohn is a bit too clever. I haven’t done a survey but I’d wager the results would be pretty simple: it’s Don Draper stupid. While I agree that much of the characterization and background of the central character is overwrought and unsubtle (“meretricious,” “literally,” the reviewer jokes, assuming we all know the etymology of the word), I would suggest this only makes the question of his overwhelming attractiveness all the more fascinating. Mendelsohn finds him flat. But, at least in his review, he overlooks all the crucial scenes and instead, understandably, focuses on the lame flashbacks that supposedly explain his bad behavior.

All the characters are racist, Mendelsohn charges. But in the first scene of the first episode Don notices that the black busser clearing his table is smoking a rival brand of cigarettes—that he’s a potential new customer for his clients—and casually asks him what it would take for him to switch brands. When the manager arrives at the table to chide the busser for being so talkative, Don is as shocked as we are. I can’t recall a single scene in which Don is overtly racist.

Then there’s the relationship between Don and Peggy, which, as difficult as it is to believe for all the other characters, is never sexual. Everyone is sexist, yet in the first scene bringing together Don, Peggy, and Pete, our protagonist ends up chiding the younger man, who has been giving Peggy a fashion lesson, for being disrespectful. In season two, we see Don in an elevator with two men, one of whom is giving the raunchy details of his previous night’s conquest and doesn’t bother to pause the recounting when a woman enters. Her face registers something like terror, Don’s unmistakable disgust. “Take your hat off,” he says to the offender, and for a brief moment you wonder if the two men are going to tear into him. Then Don reaches over, unchecked, removes the man’s hat, and shoves it into his chest, rendering both men silent for the duration of the elevator ride. I hate to be one of those critics who reflexively resort to their pet theory, but my enjoyment of the scene long preceded my realization that it entailed an act of altruistic punishment.

The opening credits say it all, as we see a silhouetted man, obviously Don, walking into an office which begins to collapse, and cuts to him falling through the sky against the backdrop of skyscrapers with billboards and snappy slogans. How far will Don fall? For that matter, how far will Peggy? Their experiences oddly mirror each other, and it becomes clear that while Don barks denunciations at the other members of his creative team, he often goes out of his way to mentor Peggy. He’s the one, in fact, who recognizes her potential and promotes her from a secretary to a copywriter, a move which so confounds all the other men that they conclude he must have knocked her up.

Mendelsohn is especially disappointed in Mad Men’s portrayal, or rather its failure to portray, the plight of closeted gays. He complains that when Don witnesses Sal Romano kissing a male bellhop in a hotel on a business trip, the revelation “weirdly” “has no repercussions.” But it’s not weird at all because we experience some of Sal’s anxiety about how Don will react. On the plain home, Sal is terrified, but Don rather subtly lets him know he has nothing to worry about. Don can sympathize about having secrets. We can just imagine if one of the characters other than Don had been the one to discover Sal’s homosexuality—actually we don’t have to imagine it because it happens later.

Unlike the other characters, Don’s vices, chief among them his philandering, are timeless (except his chain-smoking) and universal. And though we can’t forgive him for what he does to Betty (another annoying character, who, like some women I’ve dated, uses the strategy of being constantly aggrieved to trick you into being nice to her, which backfires because the suggestion that your proclivities aren’t nice actually provokes you), we can’t help hoping that he’ll find a way to redeem himself. As cheesy as they are, the scenes that have Don furrowing his brow and extemporizing on what people want and how he can turn it into a marketing strategy, along with the similar ones in which he feels the weight of his crimes against others, are my favorites. His voice has the amazing quality of being authoritative and yet at the same time signaling vulnerability. This guy should be able to get it. But he’s surrounded by vipers. His job is to lie. His identity is a lie he can’t escape. How will he preserve his humanity, his soul? Or will he? These questions, and similar ones about Peggy, are what keep me watching.

Don Draper, then, is a character from a long tradition of bad boys who give contradictory signals of their moral worth. Milton inadvertently discovered how powerful these characters are when Satan turned out to be by far the most compelling character in Paradise Lost. (Byron understood why immediately.) George Lucas made a similar discovery when Han Solo stole the show from Luke Skywalker. From Tom Sawyer to Jack Sparrow and Tony Soprano (Weiner was also a writer on that show), the fascination with these guys savvy enough to get away with being bad but sensitive and compassionate enough to feel bad about it has been taking a firm grip on audiences sympathies since long before Don Draper put on his hat.

A couple final notes on the show's personal appeal for me: given my interests and education, marketing and advertising would be a natural fit for me, absent my moral compunctions about deceiving people to their detriment to enrich myself. Still, it's nice to see a show focusing on the processes behind creativity. Then there's the scene in season four in which Don realizes he's in love with his secretary because she doesn't freak out when his daughter spills her milkshake. Having spent too much of my adult life around women with short fuses, and so much of my time watching Mad Men being annoyed with Betty, I laughed until I teared up.

Also read:

SYMPATHIZING WITH PSYCHOS: WHY WE WANT TO SEE ALEX ESCAPE HIS FATE AS A CLOCKWORK ORANGE

THE ADAPTIVE APPEAL OF BAD BOYS

SABBATH SAYS: PHILIP ROTH AND THE DILEMMAS OF IDEOLOGICAL CASTRATION

The Inverted Pyramid: Our Millennia-Long Project of Keeping Alpha Males in their Place

Imagine this familiar hypothetical scenario: you’re a prehistoric hunter, relying on cleverness, athleticism, and well-honed skills to track and kill a gazelle on the savannah. After carting the meat home, your wife is grateful—or your wives rather. As the top hunter in the small tribe with which your family lives and travels, you are accorded great power over all the other men, just as you enjoy great power over your family. You are the leader, the decision-maker, the final arbiter of disputes and the one everyone looks to for direction in times of distress. The payoff for all this responsibility is that you and your family enjoy larger shares of whatever meat is brought in by your subordinates. And you have sexual access to almost any woman you choose. Someday, though, you know your prowess will be on the wane, and you’ll be subjected to more and more challenges from younger men, until eventually you will be divested of all your authority. This is the harsh reality of man the hunter.

It’s easy to read about “chimpanzee politics” (I’ll never forget reading Frans de Waal’s book by that title) or watch nature shows in which the stentorian, accented narrator assigns names and ranks to chimps or gorillas and then, looking around at the rigid hierarchies of the institutions where we learn or where we work, as well as those in the realm of actual human politics, and conclude that there must have been a pretty linear development from the ancestors we share with the apes to the eras of pharaohs and kings to the Don Draperish ‘60’s till today, at least in terms of our natural tendency to form rank and follow leaders.

What to make, then, of these words spoken to anthropologist Richard Lee by a hunter-gatherer teaching him of the ways of the !Kung San?

“Say that a man has been hunting. He must not come home and announce like a braggart, ‘I have killed a big one in the bush!’ He must first sit down in silence until I or someone else comes up to his fire and asks, ‘What did you see today?’ He replies quietly, ‘Ah, I’m no good for hunting. I saw nothing at all…maybe just a tiny one.’ Then I smile to myself because I now know he has killed something big.” (Quoted in Boehm 45)

Even more puzzling from a selfish gene perspective is that the successful hunter gets no more meat for himself or his family than any of the other hunters. They divide it equally. Lee asked his informants why they criticized the hunters who made big kills.

“When a young man kills much meat, he comes to think of himself as a chief or big man, and he thinks of the rest of us as his servants or inferiors. We can’t accept this.”

So what determines who gets to be the Alpha, if not hunting prowess? According to Christopher Boehm, the answer is simple. No one gets to be the Alpha. “A distinctly egalitarian political style is highly predictable wherever people live in small, locally autonomous social and economic groups” (36). These are exactly the types of groups humans have lived in for the vast majority of their existence on Earth. This means that, uniquely among the great apes, humans evolved mechanisms to ensure egalitarianism alongside those for seeking and submitting to power.

Boehm’s Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior is a miniature course in anthropology, as dominance and submission—as well as coalition building and defiance—are examined not merely in the ethnographic record, but in the ethological descriptions of our closest ape relatives. Building on Bruce Knauft’s observations of the difference between apes and hunter-gatherers, Boehm argues that “with respect to political hierarchy human evolution followed a U-shaped trajectory” (65). But human egalitarianism is not based on a simple of absence of hierarchy; rather, Boehm theorizes that the primary political actors (who with a few notable exceptions tend to be men) decide on an individual basis that, while power may be desirable, the chances of any individual achieving it are small, and the time span during which he would be able to sustain it would be limited. Therefore, they all submit to the collective will that no man should have authority over any other, thus all of them maintain their own personal autonomy. Boehm explains