READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

Intuition vs. Science: What's Wrong with Your Thinking, Fast and Slow

Kahneman has no faith in our ability to clean up our thinking. He’s an expert on all the ways thinking goes awry, and even he catches himself making all the common mistakes time and again. So he proposes a way around the impenetrable wall of cognitive illusion and self-justification. If all the people gossiping around the water cooler are well-versed in the language of biases and heuristics and errors of intuition, we may all benefit because anticipating gossip can have a profound effect on behavior. No one wants to be spoken of as the fool.

From Completely Useless to Moderately Useful

In 1955, a twenty-one-year-old Daniel Kahneman was assigned the formidable task of creating an interview procedure to assess the fitness of recruits for the Israeli army. Kahneman’s only qualification was his bachelor’s degree in psychology, but the state of Israel had only been around for seven years at the time so the Defense Forces were forced to satisfice. In the course of his undergraduate studies, Kahneman had discovered the writings of a psychoanalyst named Paul Meehl, whose essays he would go on to “almost memorize” as a graduate student. Meehl’s work gave Kahneman a clear sense of how he should go about developing his interview technique.

If you polled psychologists today to get their predictions for how successful a young lieutenant inspired by a book written by a psychoanalyst would be in designing a personality assessment protocol—assuming you left out the names—you would probably get some dire forecasts. But Paul Meehl wasn’t just any psychoanalyst, and Daniel Kahneman has gone on to become one of the most influential psychologists in the world. The book whose findings Kahneman applied to his interview procedure was Clinical vs. Statistical Prediction: A Theoretical Analysis and a Review of the Evidence, which Meehl lovingly referred to as “my disturbing little book.” Kahneman explains,

Meehl reviewed the results of 20 studies that had analyzed whether clinical predictions based on the subjective impressions of trained professionals were more accurate than statistical predictions made by combining a few scores or ratings according to a rule. In a typical study, trained counselors predicted the grades of freshmen at the end of the school year. The counselors interviewed each student for forty-five minutes. They also had access to high school grades, several aptitude tests, and a four-page personal statement. The statistical algorithm used only a fraction of this information: high school grades and one aptitude test. (222)

The findings for this prototypical study are consistent with those arrived at by researchers over the decades since Meehl released his book:

The number of studies reporting comparisons of clinical and statistical predictions has increased to roughly two hundred, but the score in the contest between algorithms and humans has not changed. About 60% of the studies have shown significantly better accuracy for the algorithms. The other comparisons scored a draw in accuracy, but a tie is tantamount to a win for the statistical rules, which are normally much less expensive to use than expert judgment. No exception has been convincingly documented. (223)

Kahneman designed the interview process by coming up with six traits he thought would have direct bearing on a soldier’s success or failure, and he instructed the interviewers to assess the recruits on each dimension in sequence. His goal was to make the process as systematic as possible, thus reducing the role of intuition. The response of the recruitment team will come as no surprise to anyone: “The interviewers came close to mutiny” (231). They complained that their knowledge and experience were being given short shrift, that they were being turned into robots. Eventually, Kahneman was forced to compromise, creating a final dimension that was holistic and subjective. The scores on this additional scale, however, seemed to be highly influenced by scores on the previous scales.

When commanding officers evaluated the new recruits a few months later, the team compared the evaluations with their predictions based on Kahneman’s six scales. “As Meehl’s book had suggested,” he writes, “the new interview procedure was a substantial improvement over the old one… We had progressed from ‘completely useless’ to ‘moderately useful’” (231).

Kahneman recalls this story at about the midpoint of his magnificent, encyclopedic book Thinking, Fast and Slow. This is just one in a long series of run-ins with people who don’t understand or can’t accept the research findings he presents to them, and it is neatly woven into his discussions of those findings. Each topic and each chapter feature a short test that allows you to see where you fall in relation to the experimental subjects. The remaining thread in the tapestry is the one most readers familiar with Kahneman’s work most anxiously anticipated—his friendship with AmosTversky, with whom he shared the Nobel prize in economics in 2002.

Most of the ideas that led to experiments that led to theories which made the two famous and contributed to the founding of an entire new field, behavioral economics, were borne of casual but thrilling conversations both found intrinsically rewarding in their own right. Reading this book, as intimidating as it appears at a glance, you get glimmers of Kahneman’s wonder at the bizarre intricacies of his own and others’ minds, flashes of frustration at how obstinately or casually people avoid the implications of psychology and statistics, and intimations of the deep fondness and admiration he felt toward Tversky, who died in 1996 at the age of 59.

Pointless Punishments and Invisible Statistics

When Kahneman begins a chapter by saying, “I had one of the most satisfying eureka experiences of my career while teaching flight instructors in the Israeli Air Force about the psychology of effective training” (175), it’s hard to avoid imagining how he might have relayed the incident to Amos years later. It’s also hard to avoid speculating about what the book might’ve looked like, or if it ever would have been written, if he were still alive. The eureka experience Kahneman had in this chapter came about, as many of them apparently did, when one of the instructors objected to his assertion, in this case that “rewards for improved performance work better than punishment of mistakes.” The instructor insisted that over the long course of his career he’d routinely witnessed pilots perform worse after praise and better after being screamed at. “So please,” the instructor said with evident contempt, “don’t tell us that reward works and punishment does not, because the opposite is the case.” Kahneman, characteristically charming and disarming, calls this “a joyous moment of insight” (175).

The epiphany came from connecting a familiar statistical observation with the perceptions of an observer, in this case the flight instructor. The problem is that we all have a tendency to discount the role of chance in success or failure. Kahneman explains that the instructor’s observations were correct, but his interpretation couldn’t have been more wrong.

What he observed is known as regression to the mean, which in that case was due to random fluctuations in the quality of performance. Naturally, he only praised a cadet whose performance was far better than average. But the cadet was probably just lucky on that particular attempt and therefore likely to deteriorate regardless of whether or not he was praised. Similarly, the instructor would shout into the cadet’s earphones only when the cadet’s performance was unusually bad and therefore likely to improve regardless of what the instructor did. The instructor had attached a causal interpretation to the inevitable fluctuations of a random process. (175-6)

The roster of domains in which we fail to account for regression to the mean is disturbingly deep. Even after you’ve learned about the phenomenon it’s still difficult to recognize the situations you should apply your understanding of it to. Kahneman quotes statistician David Freedman to the effect that whenever regression becomes pertinent in a civil or criminal trial the side that has to explain it will pretty much always lose the case. Not understanding regression, however, and not appreciating how it distorts our impressions has implications for even the minutest details of our daily experiences. “Because we tend to be nice to other people when they please us,” Kahneman writes, “and nasty when they do not, we are statistically punished for being nice and rewarded for being nasty” (176). Probability is a bitch.

The Illusion of Skill in Stock-Picking

Probability can be expensive too. Kahneman recalls being invited to give a lecture to advisers at an investment firm. To prepare for the lecture, he asked for some data on the advisers’ performances and was given a spreadsheet for investment outcomes over eight years. When he compared the numbers statistically, he found that none of the investors was consistently more successful than the others. The correlation between the outcomes from year to year was nil. When he attended a dinner the night before the lecture “with some of the top executives of the firm, the people who decide on the size of bonuses,” he knew from experience how tough a time he was going to have convincing them that “at least when it came to building portfolios, the firm was rewarding luck as if it were a skill.” Still, he was amazed by the execs’ lack of shock:

We all went on calmly with our dinner, and I have no doubt that both our findings and their implications were quickly swept under the rug and that life in the firm went on just as before. The illusion of skill is not only an individual aberration; it is deeply ingrained in the culture of the industry. Facts that challenge such basic assumptions—and thereby threaten people’s livelihood and self-esteem—are simply not absorbed. (216)

The scene that follows echoes the first chapter of Carl Sagan’s classic paean to skepticism Demon-Haunted World, where Sagan recounts being bombarded with questions about science by a driver who was taking him from the airport to an auditorium where he was giving a lecture. He found himself explaining to the driver again and again that what he thought was science—Atlantis, aliens, crystals—was, in fact, not. "As we drove through the rain," Sagan writes, "I could see him getting glummer and glummer. I was dismissing not just some errant doctrine, but a precious facet of his inner life" (4). In Kahneman’s recollection of his drive back to the airport after his lecture, he writes of a conversation he had with his own driver, one of the execs he’d dined with the night before.

He told me, with a trace of defensiveness, “I have done very well for the firm and no one can take that away from me.” I smiled and said nothing. But I thought, “Well, I took it away from you this morning. If your success was due mostly to chance, how much credit are you entitled to take for it? (216)

Blinking at the Power of Intuitive Thinking

It wouldn’t surprise Kahneman at all to discover how much stories like these resonate. Indeed, he must’ve considered it a daunting challenge to conceive of a sensible, cognitively easy way to get all of his vast knowledge of biases and heuristics and unconscious, automatic thinking into a book worthy of the science—and worthy too of his own reputation—while at the same time tying it all together with some intuitive overarching theme, something that would make it read more like a novel than an encyclopedia.

Malcolm Gladwell faced a similar challenge in writing Blink: the Power of Thinking without Thinking, but he had the advantages of a less scholarly readership, no obligation to be comprehensive, and the freedom afforded to someone writing about a field he isn’t one of the acknowledged leaders and creators of. Ultimately, Gladwell’s book painted a pleasing if somewhat incoherent picture of intuitive thinking. The power he refers to in the title is over the thoughts and actions of the thinker, not, as many must have presumed, to arrive at accurate conclusions.

It’s entirely possible that Gladwell’s misleading title came about deliberately, since there’s a considerable market for the message that intuition reigns supreme over science and critical thinking. But there are points in his book where it seems like Gladwell himself is confused. Robert Cialdini, Steve Marin, and Noah Goldstein cover some of the same research Kahneman and Gladwell do, but their book Yes!: 50 Scientifically Proven Ways to be Persuasive is arranged in a list format, with each chapter serving as its own independent mini-essay.

Early in Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman introduces us to two characters, System 1 and System 2, who pass the controls of our minds back and forth between themselves according the expertise and competency demanded by current exigency or enterprise. System 1 is the more intuitive, easygoing guy, the one who does what Gladwell refers to as “thin-slicing,” the fast thinking of the title. System 2 works deliberately and takes effort on the part of the thinker. Most people find having to engage their System 2—multiply 17 by 24—unpleasant to one degree or another.

The middle part of the book introduces readers to two other characters, ones whose very names serve as a challenge to the field of economics. Econs are the beings market models and forecasts are based on. They are rational, selfish, and difficult to trick. Humans, the other category, show inconsistent preferences, changing their minds depending on how choices are worded or presented, are much more sensitive to the threat of loss than the promise of gain, are sometimes selfless, and not only can be tricked with ease but routinely trick themselves. Finally, Kahneman introduces us to our “Two Selves,” the two ways we have of thinking about our lives, either moment-to-moment—experiences he, along with Mihaly Csikzentmihhalyi (author of Flow) pioneered the study of—or in abstract hindsight. It’s not surprising at this point that there are important ways in which the two selves tend to disagree.

Intuition and Cerebration

The Econs versus Humans distinction, with its rhetorical purpose embedded in the terms, is plenty intuitive. The two selves idea, despite being a little too redolent of psychoanalysis, also works well. But the discussions about System 1 and System 2 are never anything but ethereal and abstruse. Kahneman’s stated goal was to discuss each of the systems as if they were characters in a plot, but he’s far too concerned with scientifically precise definitions to run with the metaphor. The term system is too bloodless and too suggestive of computer components; it’s too much of the realm of System 2 to be at all satisfying to System 1. The collection of characteristics Thinking links to the first system (see a list below) is lengthy and fascinating and not easily summed up or captured in any neat metaphor. But we all know what Kahneman is talking about. We could use mythological figures, perhaps Achilles or Orpheus for System 1 and Odysseus or Hephaestus for System 2, but each of those characters comes with his own narrative baggage. Not everyone’s System 1 is full of rage like Achilles, or musical like Orpheus. Maybe we could assign our System 1s idiosyncratic totem animals.

But I think the most familiar and the most versatile term we have for System 1 is intuition. It is a hairy and unpredictable beast, but we all recognize it. System 2 is actually the harder to name because people so often mistake their intuitions for logical thought. Kahneman explains why this is the case—because our cognitive resources are limited our intuition often offers up simple questions as substitutes from more complicated ones—but we must still have a term that doesn’t suggest complete independence from intuition and that doesn’t imply deliberate thinking operates flawlessly, like a calculator. I propose cerebration. The cerebral cortex rests on a substrate of other complex neurological structures. It’s more developed in humans than in any other animal. And the way it rolls trippingly off the tongue is as eminently appropriate as the swish of intuition. Both terms work well as verbs too. You can intuit, or you can cerebrate. And when your intuition is working in integrated harmony with your cerebration you are likely in the state of flow Csikzentmihalyi pioneered the study of.

While Kahneman’s division of thought into two systems never really resolves into an intuitively manageable dynamic, something he does throughout the book, which I initially thought was silly, seems now a quite clever stroke of brilliance. Kahneman has no faith in our ability to clean up our thinking. He’s an expert on all the ways thinking goes awry, and even he catches himself making all the common mistakes time and again. In the introduction, he proposes a way around the impenetrable wall of cognitive illusion and self-justification. If all the people gossiping around the water cooler are well-versed in the language describing biases and heuristics and errors of intuition, we may all benefit because anticipating gossip can have a profound effect on behavior. No one wants to be spoken of as the fool.

Kahneman writes, “it is much easier, as well as far more enjoyable, to identify and label the mistakes of others than to recognize our own.” It’s not easy to tell from his straightforward prose, but I imagine him writing lines like that with a wry grin on his face. He goes on,

Questioning what we believe and want is difficult at the best of times, and especially difficult when we most need to do it, but we can benefit from the informed opinions of others. Many of us spontaneously anticipate how friends and colleagues will evaluate our choices; the quality and content of these anticipated judgments therefore matters. The expectation of intelligent gossip is a powerful motive for serious self-criticism, more powerful than New Year resolutions to improve one’s decision making at work and at home. (3)

So we encourage the education of others to trick ourselves into trying to be smarter in their eyes. Toward that end, Kahneman ends each chapter with a list of sentences in quotation marks—lines you might overhear passing that water cooler if everyone where you work read his book. I think he’s overly ambitious. At some point in the future, you may hear lines like “They’re counting on denominator neglect” (333) in a boardroom—where people are trying to impress colleagues and superiors—but I seriously doubt you’ll hear it in the break room. Really, what he’s hoping is that people will start talking more like behavioral economists. Though some undoubtedly will, Thinking, Fast and Slow probably won’t ever be as widely read as, say, Freud’s lurid pseudoscientific On the Interpretation of Dreams. That’s a tragedy.

Still, it’s pleasant to think about a group of friends and colleagues talking about something other than football and American Idol. Characteristics of System 1 (105): Try to come up with a good metaphor.·

generates impressions, feelings, and inclinations; when endorsed by System 2 these become beliefs, attitudes, and intentions·

operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort, and no sense of voluntary control·

can be programmed by System 2 to mobilize attention when particular patterns are detected (search) ·

executes skilled responses and generates skilled intuitions, after adequate training·

creates a coherent pattern of activated ideas in associative memory·

links a sense of cognitive ease to illusions of truth, pleasant feelings, and reduced vigilance·

distinguishes the surprising from the normal·

infers and invents causes and intentions·

neglects ambiguity and suppresses doubt·

is biased to believe and confirm·

exaggerates emotional consistency (halo effect)·

focuses on existing evidence and ignores absent evidence (WYSIATI)·

generates a limited set of basic assessments·

represents sets by norms and prototypes, does not integrate·

matches intensities across scales (e.g., size and loudness)·

computes more than intended (mental shotgun)·

sometimes substitutes an easier question for a difficult one (heuristics) ·

is more sensitive to changes than to states (prospect theory)·

overweights low probabilities.

shows diminishing sensitivity to quantity (psychophysics)·

responds more strongly to losses than to gains (loss aversion)·

frames decision problems narrowly, in isolation from one another

Also read:

LAB FLIES: JOSHUA GREENE’S MORAL TRIBES AND THE CONTAMINATION OF WALTER WHITE

In Honor of Charles Dickens on the 200th Anniversary of His Birth

A poem about the effects of reading fiction on one’s life and perspective, inspired by Charles Dickens.

DISTRACTION

He wakes up every day and reads

most days only for a few minutes

before he has to work the fields.

He always plans to read more

before he goes to sleep but

the candlelight and exhaustion

put the plan neatly away.

He hates the reading,

wonders if he should find

something other than Great Expectations.

But he doesn’t have

any other books,

and he thinks of reading

like he thinks of church.

And one Sunday after sleeping

through the sermon,

he comes home and picks up

his one book.

He finds his place

planning to read just

those few minutes

but goes on and on.

The line that gets him

is about how “our worst

weaknesses and meanness”

are “for the sake of” those

“we most despise.”

He reads it over and over

and then goes on intent

on making sense of the words

and finding that they make their own.

After a while he stops to consider

beginning the entire book again

feeling he’s missed too much

but he goes back to where he left off.

The next day in the field he puts

everything he sees into silent words

and that night he reads for the first time

before falling asleep.

The next day in the field he describes

to himself his feelings about his work

and later holds things in their places

with words as he moves around in time.

The words are the only constant,

as even their objects can shift

through his life, childhood,

senility, and through the life of the land.

He wants to write down his days on paper

because he believes if he does then he can

go anywhere, do anything, and yet still

there he’ll be.

It’s not that Dickens was right that got him,

but that he was wrong—

even Pip must’ve known his worst

wasn’t for anyone but Estella,

nor his best.

One day could stretch to a whole

book of bound pages like the one

in his hands, or it could start and finish

on just one.

He imagines writing right over

the grand typeset words of Dickens'

on page one, “Hard to believe,

I woke up, excited to read.

I wished I could keep reading all day.”

Sunday, June 22, 2008, 11:43 am.

Also read:

Secret Dancers

And:

Gracie - Invisible Fences

Gracie - Invisible Fences

A poem inspired by C.K. Williams about what happened when my childhood friend’s parents got an invisible fence for their dog Gracie.

Invisible Fences

I hated Tony’s parents even more than I had before when I heard about the “invisible fence” for Gracie.

They were altogether too strict, overly vigilant, intrusive in their son’s, my friend’s, life, and so unjustifiedly.

He and I were the shy ones, the bookish, artistic, sensitive ones—really both of us were conscientious to a fault.

What we needed was encouragement, always some sort of bolstering, but what Tony got was questioned and stifled.

And here was Gracie, a German shorthair, damn good dog, spirited, set to be broken by similarly unjustified treatment.

As dumb kids we of course had to sample the “mild shock” Gracie would receive should she venture too near the property line.

It seemed not so mild to me, a teenager, with big dreams, held back, I felt, by myriad unnecessary qualities of myself—

qualities I must master, vanquish—and yet here were Tony’s parents, putting up still more arbitrary boundaries.

I could barely stand to hear about Gracie’s march of shameful submission, conditioning to a high-pitched warning.

She started whimpering and shaking, and looking up with plangent eyes at her merciless or misguided master—

this by the second lap along the border of the yard, so she’d learn never to get shocked—it was all “for her own good.”

The line infuriated me more than any lie I’d ever heard, as there was no question whose convenience was really being served.

That first day after Gracie had been trained as directed, Tony and I were walking away from his house,

and I looked back, stopping, to see her longingly looking, desperately watching us leave her, leaving me sighing.

I shook my head, frowned, subtly slumped, which maybe she saw, because just then a change came over her.

She fell silent, her ears fell flat to her brown, bullet-shaped head, her body tensed as she lifted herself from her haunches.

And then she shot forth her willowy, maculated body in long, determined strides, but keeping low all the while,

as if somehow intuiting that the impending pain was simply a manifestation of her master’s hand to be ducked under.

My mouth fell open in thrilled astonishment, and as she neared the buried line, I shouted, “Yeah Gracie! Come on!”

Tony likewise thrilled to the feat his old friend was about to perform, shouting alongside me, “Come on girl! You can make it!”

About the time Gracie would have been heedlessly hearing the warning beep, my excitement turned darker.

Simultaneous with the shock I barked, “Go Gracie! Fuck ‘em!” with a maniacal, demoniacal, spitting abandon.

Without the slightest whimper Gracie broke through the boundary, ducked under the blow, defying her master’s dictates.

“Yeah! Fuck ‘em!” I enjoined again, my head jolting, thrashing out the words, erupting with all the force of self-loathing.

If Tony had any apprehensions about hearing his parents so cursed he never voiced them—was I really cursing them?

Gracie approached atremble, all frenzy from her jolting accomplishment and now met by our wild acclaim and eager praise,

or not praise so much as gratitude, as she anxiously darted between and around us as if disoriented, reeling, overwhelmed.

But Tony and I knew exactly what we had just witnessed, the toppling of guilt’s tyranny, a spirit’s willful, gasping escape.

Our deliverance lasted hours, while we idly ambled about and between neighborhoods, casting spiteful glances

along the endless demarcations of land, owned, separated, displayed, individual kingdoms, badges of well-lived,

well-governed lives—I wanted to tromp through all those manicured front lawns, my every step spreading pestilence

to the too-green grass we weren’t supposed to walk on lest it wear a trail, ruining the pristine quality of ownership.

Our march of euphoric defiance inspired by Gracie’s coup de grace could only go on for so long, though—

we were newly free, but free to do what?—before we’d have to return home for a meal, shelter, electronic entertainment.

As the sun sank, I began to have the sense of squandered opportunity, dreading the end of my reprieve from invisible impediments.

Back toward Tony’s house we hesitantly made our way, but all the while I kept the image of Gracie’s escape fresh in mind.

My friend and I took up conversing as we neared the stretch of road by his house, ranging widely and irreverently—

our discourses having served as our sole escape up to then—in the tone and spirit of seeing right through everything.

We were both halfway up Tony’s driveway before we noticed that Gracie was no longer keeping pace with us.

…She was turning tight circles in the street, whimpering, anxious, and seeing her, Tony and I exchanged a look I’ll never forget.

Even after removing the device from Gracie’s neck, we still had to lift her, squirming desperately, over the line to get her home.

Also read:

IN HONOR OF CHARLES DICKENS ON THE 200TH ANNIVERSARY OF HIS BIRTH

And:

Secret Dancers

Secret Dancers

A poem about a graduate student in psychology sees a woman with Parkinson’s while working as a server. It sets off a series of reflections and revelations. Another piece inspired by C.K. Williams (along with Ian McEwan).

For about 3 years, I was a bit obsessed with C.K. Williams's poems. They usually tell stories, and rather than worrying over whether his words impose some burden of meaning on his subjects, Williams uses words to discover the meanings that exist independent of them. The result is a stripping away of tired, habituated ways of seeing to make way for new revelation.

This poem was also inspired by Ian McEwan's novel Saturday, which focuses on a day in the life of a neurosurgeon. Anyway, I really love how this poem turned out, but it's so derivative I feel I have to cite my inspirations.

Secret Dancers

The woman on the right side of the booth as I approach—“Can I get you something to drink?”—I noticed had something wrong with her,

the way she walked, the way she moved, when I led her with her friend, much older,

her mother perhaps, from the door—“Hello, will it be just the two of you today?”—to where they sit, in my section, scanning the menu for that one item.

“I’d just like water with lemon,” the one on the left says, the older one, the mother.

I nod, repeating, “water with lemon,” as I turn to the other, like I always turn from one to the next,

but this time with an added eagerness, with a curiosity I know may offend, and I see my diagnosis was correct,

for the woman cannot, does not, sit still, cannot be still, but jerks and sways, as if unable to establish equilibrium, find a balanced middle.

I’m glad, hurrying to the fountains, as I always do, the woman said, in essence, “For me too,”

because I’ve already lost her words in the deluge of the disturbance, the rarity, the tragedy of the sight

of her involuntary dance—chorea—which is, aside from the movement, nothing at all like a dance, more an antidance,

signaling things opposite to what real dancers do with their performances.

I watch my hands do by habit the filling of plastic cups with ice and water, reach for straws and lemons,

still seeing her, slipping though sitting, and doing my own semantic antidance in my mind:

“How could anyone go on believing… after seeing… dopamine… substantia nigra…

choreographed by nucleotides—no one ever said the vestibular structure, the loop under the ear

with the tiny floating bone that gives us, that is our sense of balance, was implicated… so important to see.”

In the kitchen, sorting dishes by shape on the stainless steal table on their way to being washed,

I call to the pretty young cook I sort of love, who sort of loves but sort of hates me

for the sorts of things I say (noticing and questioning), and say, “There’s a woman with Parkinson’s

at table three—you should come look,” and feel chastised by an invisible authority

(somewhere in my frontal lobe I suspect) before the suggestion can even be acknowledged.

Look? Are we to examine her, make her a specimen, or gawk, like at a freak? But it—she is so important to see,

I set to formulating a new category of looking.

I begin with the varieties of suffering so proudly and annoyingly on display: abuse, or “abuse”, survived,

poverty escaped, gangsta rappers shot or imprisoned to earn their street cred,

chains of slights and abandonments by ex-lovers, all heard so frequently, boasted of as markers of authenticity.

Is there a way, I wonder, to look that would serve as tribute to the woman’s much more literal,

much more real perseverance and courage, a registering and appreciation of identity,

that precious plumage that renders each of us findable in the endless welter and noise

of faces and the dubious stories of heroism attached to them?

Returning to the booth to take the women’s orders, so awkward, so wrong, the looking, I discover,

cannot be condoned under my new rubric because the sufferer’s antidance is leading her in the wrong direction.

Those stories of abuse, penury, assaults or arrests, and recurrent dealings with unfaithful lovers all go from bad,

the worse the better, to better but never too good. This story, like nearly all real and authentic stories, is about deterioration.

So I type their orders on the touch screen computer, defeated, chastened, as if curiosity—

noticing and questioning—leads irredeemably to taboo

(but how lucky to be born with this affliction instead of one more incapacitating!)

I’m left sulking a little, and thinking about dancing and movement that goes by the name

but isn’t. “Dance Champ!” they exhorted Ali from ringside in Zaire,

when he’d decided, strategically,

and it turned out successfully, not to. Ali, The Greatest, the star and subject of movies, King of Classic Sports on ESPN,

his not quite dancing featured so prominently, so inescapably—look all you want, look and be awed—but all in the past.

You forget the man is still alive. The secrecy makes me wonder: is it economic, is it political?

The visibility, the stark advertisement of achievers of the formerly impossible, the heroically,

the monstrously successful, coupled with the tabooed hiding away of the vastly more numerous unfortunate,

fallen, and afflicted—the lifeblood, the dangling American Dream, insufficient,

the market for better lives necessitates the beating heart of

belief, “You can do anything...,” be your heroes, be heroes for others, by working,

spending, studying, being industrious, acquisitive, but never, never questioning and only

curious to a degree, “…anything you put your” (antidancing) “mind to.”

As I carry the plates, one in the crook between palm and thumb in my left hand, the other

balanced over it on my wrist so I have a free hand to grab the ketchup

on my way to the booth, I recall uneasily watching Ali, his arm outstretched,

antidancing as he lit the Olympic Torch.

Also read:

GRACIE - INVISIBLE FENCES

IN HONOR OF CHARLES DICKENS ON THE 200TH ANNIVERSARY OF HIS BIRTH

The Upper Hand in Relationships

What began as an exercise in SEO (search engine optimization) became such a success it’s probably my most widely read piece of writing (somewhat to my chagrin). Apparently, my background in psychology and long history of dating equipped me with some helpful insight. Bottom line: stay away from people playing zero-sum games. And don’t give away too much too soon. You’ll have to read to find out more about what made this post so popular.

People perform some astoundingly clever maneuvers in pursuit of the upper hand in their romantic relationships, and some really stupid ones too. They try to make their partners jealous. They feign lack of interest. They pretend to have enjoyed wild success in the realm of dating throughout their personal histories, right up until the point at which they met their current partners. The edge in cleverness, however, is usually enjoyed by women—though you may be inclined to call it subtlety, or even deviousness.

Some of the most basic dominance strategies used in romantic relationships are based either on one partner wanting something more than the other, or on one partner being made to feel more insecure than the other. We all know couples whose routine revolves around the running joke that the man is constantly desperate for sex, which allows the woman to set the terms he must meet in order to get some. His greater desire for sex gives her the leverage to control him in other domains. I’ll never forget being nineteen and hearing a friend a few years older say of her husband, “Why would I want to have sex with him when he can’t even remember to take out the garbage?” Traditionally, men held the family purse strings, so they—assuming they or their families had money—could hold out the promise of things women wanted more. Of course, some men still do this, giving their wives little reminders of how hard they work to provide financial stability, or dropping hints of their extravagant lifestyles to attract prospective dates.

You can also get the upper hand on someone by taking advantage of his or her insecurities. (If that fails, you can try producing some.) Women tend to be the most vulnerable to such tactics at the moment of choice, wanting their features and graces and wiles to make them more desirable than any other woman prospective partners are likely to see. The woman who gets passed up in favor of another goes home devastated, likely lamenting the crass superficiality of our culture.

Most of us probably know a man or two who, deliberately or not, manages to keep his girlfriend or wife in constant doubt when it comes to her ability to keep his attention. These are the guys who can’t control their wandering eyes, or who let slip offhand innuendos about incremental weight gain. Perversely, many women respond by expending greater effort to win his attention and his approval.

Men tend to be the most vulnerable just after sex, in the Was-it-good-for-you moments. If you found yourself seething at some remembrance of masculine insensitivity reading the last paragraph, I recommend a casual survey of your male friends in which you ask them how many of their past partners at some point compared them negatively to some other man, or men, they had been with prior to the relationship. The idea that the woman is settling for a man who fails to satisfy her as others have plays into the narrative that he wants sex more—and that he must strive to please her outside the bedroom.

If you can put your finger on your partner’s insecurities, you can control him or her by tossing out reassurances like food pellets to a trained animal. The alternative would be for a man to be openly bowled over by a woman’s looks, or for a woman to express in earnest her enthusiasm for a man’s sexual performances. These options, since they disarm, can be even more seductive; they can be tactics in their own right—but we’re talking next-level expertise here so it’s not something you’ll see very often.

I give the edge to women when it comes to subtly attaining the upper hand in relationships because I routinely see them using a third strategy they seem to have exclusive rights to. Being the less interested party, or the most secure and reassuring party, can work wonders, but for turning proud people into sycophants nothing seems to work quite as well as a good old-fashioned guilt-trip.

To understand how guilt-trips work, just consider the biggest example in history: Jesus died on the cross for your sins, and therefore you owe your life to Jesus. The illogic of this idea is manifold, but I don’t need to stress how many people it has seduced into a lifetime of obedience to the church. The basic dynamic is one of reciprocation: because one partner in a relationship has harmed the other, the harmer owes the harmed some commensurate sacrifice.

I’m probably not the only one who’s witnessed a woman catching on to her man’s infidelity and responding almost gleefully—now she has him. In the first instance of this I watched play out, the woman, in my opinion, bore some responsibility for her husband’s turning elsewhere for love. She was brutal to him. And she believed his guilt would only cement her ascendancy. Fortunately, they both realized about that time she must not really love him and they divorced.

But the guilt need not be tied to anything as substantive as cheating. Our puritanical Christian tradition has joined forces in America with radical feminism to birth a bastard lovechild we encounter in the form of a groundless conviction that sex is somehow inherently harmful—especially to females. Women are encouraged to carry with them stories of the traumas they’ve suffered at the hands of monstrous men. And, since men are of a tribe, a pseudo-logic similar to the Christian idea of collective guilt comes into play. Whenever a man courts a woman steeped in this tradition, he is put on early notice—you’re suspect; I’m a trauma survivor; you need to be extra nice, i.e. submissive.

It’s this idea of trauma, which can be attributed mostly to Freud, that can really make a relationship, and life, fraught and intolerably treacherous. Behaviors that would otherwise be thought inconsiderate or rude—a hurtful word, a wandering eye—are instead taken as malicious attempts to cause lasting harm. But the most troubling thing about psychological trauma is that belief in it is its own proof, even as it implicates a guilty party who therefore has no way to establish his innocence.

Over the course of several paragraphs, we’ve gone from amusing but nonetheless real struggles many couples get caught up in to some that are just downright scary. The good news is that there is a subset of people who don’t see relationships as zero-sum games. (Zero-sum is a game theory term for interactions in which every gain for one party is a loss for the other. Non zero-sum games are those in which cooperation can lead to mutual benefits.) The bad news is that they can be hard to find.

There are a couple of things you can do now though that will help you avoid chess match relationships—or minimize the machinations in your current romance. First, ask yourself what dominance tactics you tend to rely on. Be honest with yourself. Recognizing your bad habits is the first step toward breaking them. And remember, the question isn’t whether you use tactics to try to get the upper hand; it’s which ones you use how often?

The second thing you can do is cultivate the habit and the mutual attitude of what’s good for one is good for the other. Relationship researcher Arthur Aron says that celebrating your partner’s successes is one of the most important things you can do in a relationship. “That’s even more important,” he says, “than supporting him or her when things go bad.” Watch out for zero-sum responses, in yourself and in your partner. And beware of zero-summers in the realm of dating.

Ladies, you know the guys who seem vaguely resentful of the power you have over them by dint of your good looks and social graces. And, guys, you know the women who make you feel vaguely guilty and set-upon every time you talk to them. The best thing to do is stay away.

But you may be tempted, once you realize a dominance tactic is being used on you, to perform some kind of countermove. It’s one of my personal failings to be too easily provoked into these types of exchanges. It is a dangerous indulgence.

Also read

Anti-Charm - Its Powers and Perils

Seduced by Satan

As long as the group they belong to is small enough for each group member to monitor the actions of the others, people can maintain strict egalitarianism, giving up whatever dominance they may desire for the assurance of not being dominated themselves. Satan very likely speaks to this natural ambivalence in humans. Benevolent leaders win our love and admiration through their selflessness and charisma. But no one wants to be a slave.

[Excerpt from Hierarchies in Hell and Leaderless Fight Clubs: Altruism, Narrative Interest, and the Adaptive Appeal of Bad Boys, my master’s thesis]

Why do we like the guys who seem not to care whether or not what they’re doing is right, but who often manage to do what’s right anyway? In the Star Wars series, Han Solo is introduced as a mercenary, concerned only with monetary reward. In the first episode of Mad Men, audiences see Don Draper saying to a woman that they should get married, and then in the final scene he arrives home to his actual wife. Tony Soprano, Jack Sparrow, Tom Sawyer, the list of male characters who flout rules and conventions, who lie, cheat and steal, but who nevertheless compel the attention, the favor, even the love of readers and moviegoers would be difficult to exhaust.

John Milton has been accused of both betraying his own and inspiring others' sympathy and admiration for what should be the most detestable character imaginable. When he has Satan, in Paradise Lost, say, “Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven,” many believed he was signaling his support of the king of England’s overthrow. Regicidal politics are well and good—at least from the remove of many generations—but voicing your opinions through such a disreputable mouthpiece? That’s difficult to defend. Imagine using a fictional Hitler to convey your stance on the current president.

Stanley Fish theorizes that Milton’s game was a much subtler one: he didn’t intend for Satan to be sympathetic so much as seductive, so that in being persuaded and won over to him readers would be falling prey to the same temptation that brought about the fall. As humans, all our hearts are marked with original sin. So if many readers of Milton’s magnum opus come away thinking Satan may have been in the right all along, the failure wasn’t the author’s unconstrained admiration for the rebel angel so much as it was his inability to adequately “justify the ways of God to men.” God’s ways may follow a certain logic, but the appeal of Satan’s ways is deeper, more primal.

In the “Argument,” or summary, prefacing Book Three, Milton relays some of God’s logic: “Man hath offended the majesty of God by aspiring to godhead and therefore, with all his progeny devoted to death, must die unless someone can be found sufficient to answer for his offence and undergo his punishment.” The Son volunteers. This reasoning has been justly characterized as “barking mad” by Richard Dawkins. But the lines give us an important insight into what Milton saw as the principle failing of the human race, their ambition to be godlike. It is this ambition which allows us to sympathize with Satan, who incited his fellow angels to rebellion against the rule of God.

In Book Five, we learn that what provoked Satan to rebellion was God’s arbitrary promotion of his own Son to a status higher than the angels: “by Decree/ Another now hath to himself ingross’t/ All Power, and us eclipst under the name/ Of King anointed.” Citing these lines, William Flesch explains, “Satan’s grandeur, even if it is the grandeur of archangel ruined, comes from his iconoclasm, from his desire for liberty.” At the same time, however, Flesch insists that, “Satan’s revolt is not against tyranny. It is against a tyrant whose place he wishes to usurp.” So, it’s not so much freedom from domination he wants, according to Flesch, as the power to dominate.

Anthropologist Christopher Boehm describes the political dynamics of nomadic peoples in his book Hierarchy in the Forest: TheEvolution of Egalitarian Behavior, and his descriptions suggest that parsing a motive of domination from one of preserving autonomy is much more complicated than Flesch’s analysis assumes. “In my opinion,” Boehm writes, “nomadic foragers are universally—and all but obsessively—concerned with being free from the authority of others” (68). As long as the group they belong to is small enough for each group member to monitor the actions of the others, people can maintain strict egalitarianism, giving up whatever dominance they may desire for the assurance of not being dominated themselves.

Satan very likely speaks to this natural ambivalence in humans. Benevolent leaders win our love and admiration through their selflessness and charisma. But no one wants to be a slave. Does Satan’s admirable resistance and defiance shade into narcissistic self-aggrandizement and an unchecked will to power? If so, is his tyranny any more savage than that of God? And might there even be something not altogether off-putting about a certain degree self-indulgent badness?

Also read:

CAMPAIGNING DEITIES: JUSTIFYING THE WAYS OF SATAN

THE ADAPTIVE APPEAL OF BAD BOYS

SYMPATHIZING WITH PSYCHOS: WHY WE WANT TO SEE ALEX ESCAPE HIS FATE AS A CLOCKWORK ORANGE

T.J. Eckleburg Sees Everything: The Great God-Gap in Gatsby part 2 of 2

The simple explanation for Fitzgerald’s decision not to gratify his readers but rather to disappoint and disturb them is that he wanted his novel to serve as an indictment of the types of behavior that are encouraged by the social conditions he describes in the story, conditions which would have been easily recognizable to many readers of his day and which persist into the Twenty-First Century.

Though The Great Gatsby does indeed tell a story of punishment, readers are left with severe doubts as to whether those who receive punishment actually deserve it. Gatsby is involved in criminal activities, and he has an affair with a married woman. Myrtle likewise is guilty of adultery. But does either deserve to die? What about George Wilson? His is the only attempt in the novel at altruistic punishment. So natural is his impulse toward revenge, however, and so given are readers to take that impulse for granted, that its function in preserving a broader norm of cooperation requires explanation. Flesch describes a series of experiments in the field of game theory centering on an exchange called the ultimatum game. One participant is given a sum of money and told he or she must propose a split with a second participant, with the proviso that if the second person rejects the cut neither will get to keep anything. Flesch points out, however, that

It is irrational for the responder not to accept any proposed split from the proposer. The responder will always come out better by accepting than by vetoing. And yet people generally veto offers of less than 25 percent of the original sum. This means they are paying to punish. They are giving up a sure gain in order to punish the selfishness of the proposer. (31)

To understand why George’s attempt at revenge is altruistic, consider that he had nothing to gain, from a purely selfish and rational perspective, and much to lose by killing the man he believed killed his wife. He was risking physical harm if a fight ensued. He was risking arrest for murder. Yet if he failed to seek revenge readers would likely see him as somehow less than human. His quest for justice, as futile and misguided as it is, would likely endear him to readers—if the discovery of how futile and misguided it was didn’t precede their knowledge of it taking place. Readers, in fact, would probably respond more favorably toward George than any other character in the story, including the narrator. But the author deliberately prevents this outcome from occurring.

The simple explanation for Fitzgerald’s decision not to gratify his readers but rather to disappoint and disturb them is that he wanted his novel to serve as an indictment of the types of behavior that are encouraged by the social conditions he describes in the story, conditions which would have been easily recognizable to many readers of his day and which persist into the Twenty-First Century. Though the narrator plays the role of second-order free-rider, the author clearly signals his own readiness to punish by publishing his narrative about such bad behavior perpetrated by characters belonging to a particular group of people, a group corresponding to one readers might encounter outside the realm of fiction.

Fitzgerald makes it obvious in the novel that beyond Tom’s simple contempt for George there exist several more severe impediments to what biologists would call group cohesion but that most readers would simply refer to as a sense of community. The idea of a community as a unified entity whose interests supersede those of the individuals who make it up is something biological anthropologists theorize religion evolved to encourage. In his book Darwin’s Cathedral, in which he attempts to explain religion in terms of group selection theory, David Sloan Wilson writes:

A group of people who abandon self-will and work tirelessly for a greater good will fare very well as a group, much better than if they all pursue their private utilities, as long as the greater good corresponds to the welfare of the group. And religions almost invariably do link the greater good to the welfare of the community of believers, whether an organized modern church or an ethnic group for whom religion is thoroughly intermixed with the rest of their culture. Since religion is such an ancient feature of our species, I have no problem whatsoever imagining the capacity for selflessness and longing to be part of something larger than ourselves as part of our genetic and cultural heritage. (175)

One of the main tasks religious beliefs evolved to handle would have been addressing the same “free-rider problem” William Flesch discovers at the heart of narrative. What religion offers beyond the social monitoring of group members is the presence of invisible beings whose concerns are tied to the collective concerns of the group.

Obviously, Tom Buchanan’s sense of community has clear demarcations. “Civilization is going to pieces,” he warns Nick as prelude to his recommendation of a book titled “The Rise of the Coloured Empires.” “The idea,” Tom explains, “is that if we don’t look out the white race will be—will be utterly submerged” (17). “We’ve got to beat them down,” Daisy helpfully, mockingly chimes in (18). While this animosity toward members of other races seems immoral at first glance, in the social context the Buchanans inhabit it actually represents a concern for the broader group, “the white race.” But Tom’s animosity isn’t limited to other races. What prompts Catherine to tell Nick how her sister “can’t stand” her husband during the gathering in Tom and Myrtle’s apartment is in fact Tom’s ridiculing of George. In response to another character’s suggestion that he’d like to take some photographs of people in Long Island “if I could get the entry,” Tom jokingly insists to Myrtle that she should introduce the man to her husband. Laughing at his own joke, Tom imagines a title for one of the photographs: “‘George B. Wilson at the Gasoline Pump,’ or something like that” (37). Disturbingly, Tom’s contempt for George based on his lowly social status has contaminated Myrtle as well. Asked by her sister why she married George in the first place, she responds, “I married him because I thought he was a gentleman…I thought he knew something about breeding but he wasn’t fit to lick my shoe” (39). Her sense of superiority, however, is based on the artificial plan for her and Tom to get married.

That Tom’s idea of who belongs to his own superior community is determined more by “breeding” than by economic success—i.e. by birth and not accomplishment—is evidenced by his attitude toward Gatsby. In a scene that has Tom stopping with two friends, a husband and wife, at Gatsby’s mansion while riding horses, he is shocked when Gatsby shows an inclination to accept an invitation to supper extended by the woman, who is quite drunk. Both the husband and Tom show their disapproval. “My God,” Tom says to Nick, “I believe the man’s coming…Doesn’t he know she doesn’t want him?” (109). When Nick points out that woman just said she did want him, Tom answers, “he won’t know a soul there.” Gatsby’s statement in the same scene that he knows Tom’s wife provokes him, as soon as Gatsby has left the room, to say, “By God, I may be old-fashioned in my ideas but women run around too much these days to suit me. They meet all kinds of crazy fish” (110). In a later scene that has Tom accompanying Daisy, with Nick in tow, to one of Gatsby’s parties, he asks, “Who is this Gatsby anyhow?... Some big bootlegger?” When Nick says he’s not, Tom says, “Well, he certainly must have strained himself to get this menagerie together” (114). Even when Tom discovers that Gatsby and Daisy are having an affair, he still doesn’t take Gatsby seriously. He calls Gatsby “Mr. Nobody from Nowhere” (137), and says, “I’ll be damned if I see how you got within a mile of her unless you brought the groceries to the back door” (138). Once he’s succeeded in scaring Daisy with suggestions of Gatsby’s criminal endeavors, Tom insists the two drive home together, saying, “I think he realizes that his presumptuous little flirtation is over” (142).

When George Wilson looks to the eyes of Dr. Eckleburg in supplication after that very car ride leads to Myrtle’s death, the fact that this “God” is an advertisement, a supplication in its own right to viewers on behalf of the optometrist to boost his business, symbolically implicates the substitution of markets for religion—or a sense of common interest—as the main factor behind Tom’s superciliously careless sense of privilege. The eyes seem such a natural stand-in for an absent God that it’s easy to take the symbolic logic for granted without wondering why George might mistake them as belonging to some sentient agent. Evolutionary psychologist Jesse Bering takes on that very question in The God Instinct: The Psychology of Souls, Destiny, and the Meaning of Life, where he cites research suggesting that “attributing moral responsibility to God is a sort of residual spillover from our everyday social psychology dealing with other people” (138). Bering theorizes that humans’ tendency to assume agency behind even random physical events evolved as a by-product of our profound need to understand the motives and intentions of our fellow humans: “When the emotional climate is just right, there’s hardly a shape or form that ‘evidence’ cannot assume. Our minds make meaning by disambiguating the meaningless” (99). In place of meaningless events, humans see intentional signs.

According to Bering’s theory, George Wilson’s intense suffering would have made him desperate for some type of answer to the question of why such tragedy has befallen him. After discussing research showing that suffering, as defined by societal ills like infant mortality and violent crime, and “belief in God were highly correlated,” Bering suggests that thinking of hardship as purposeful, rather than random, helps people cope because it allows them to place what they’re going through in the context of some larger design (139). What he calls “the universal common denominator” to all the permutations of religious signs, omens, and symbols, is the same cognitive mechanism, “theory of mind,” that allows humans to understand each other and communicate so effectively as groups. “In analyzing things this way,” Bering writes,

we’re trying to get into God’s head—or the head of whichever culturally constructed supernatural agent we have on offer… This is to say, just like other people’s surface behaviors, natural events can be perceived by us human beings as being about something other than their surface characteristics only because our brains are equipped with the specialized cognitive software, theory of mind, that enables us to think about underlying psychological causes. (79)

So George, in his bereaved and enraged state, looks at a billboard of a pair of eyes and can’t help imagining a mind operating behind them, one whose identity he’s learned to associate with a figure whose main preoccupation is the judgment of individual humans’ moral standings. According to both David Sloan Wilson and Jesse Bering, though, the deity’s obsession with moral behavior is no coincidence.

Covering some of the same game theory territory as Flesch, Bering points out that the most immediate purpose to which we put our theory of mind capabilities is to figure out how altruistic or selfish the people around us are. He explains that

in general, morality is a matter of putting the group’s needs ahead of one’s own selfish interests. So when we hear about someone who has done the opposite, especially when it comes at another person’s obvious expense, this individual becomes marred by our social judgment and grist for the gossip mills. (183)

Having arisen as a by-product of our need to monitor and understand the motives of other humans, religion would have been quickly co-opted in the service of solving the same free-rider problem Flesch finds at the heart of narratives. Alongside our concern for the reputations of others is a close guarding of our own reputations. Since humans are given to assuming agency is involved even in random events like shifts in weather, group cohesion could easily have been optimized with the subtlest suggestion that hidden agents engage in the same type of monitoring as other, fully human members of the group. Bering writes:

For many, God represents that ineradicable sense of being watched that so often flares up in moments of temptation—He who knows what’s in our hearts, that private audience that wants us to act in certain ways at critical decision-making points and that will be disappointed in us otherwise. (191)

Bering describes some of his own research that demonstrates this point. Coincident with the average age at which children begin to develop a theory of mind (around 4), they began responding to suggestions that they’re being watched by an invisible agent—named Princess Alice in honor of Bering’s mother—by more frequently resisting the temptation to avail themselves of opportunities to cheat that were built into the experimental design of a game they were asked to play (Piazza et al. 311-20). An experiment with adult participants, this time told that the ghost of a dead graduate student had been seen in the lab, showed the same results; when competing in a game for fifty dollars, they were much less likely to cheat than others who weren’t told the ghost story (Bering 193).

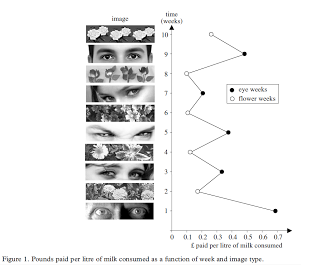

Bering also cites a study that has even more immediate relevance to George Wilson’s odd behavior vis-à-vis Dr. Eckleburg’s eyes. In “Cues of Being Watched Enhance Cooperation in a Real-World Setting,” the authors describe an experiment in which they tested the effects of various pictures placed near an “honesty box,” where people were supposed to be contributing money in exchange for milk and tea. What they found is that when the pictures featured human eyes more people contributed more money than when they featured abstract patterns of flowers. They theorize that

images of eyes motivate cooperative behavior because they induce a perception in participants of being watched. Although participants were not actually observed in either of our experimental conditions, the human perceptual system contains neurons that respond selectively to stimuli involving faces and eyes…, and it is therefore possible that the images exerted an automatic and unconscious effect on the participants’ perception that they were being watched. Our results therefore support the hypothesis that reputational concerns may be extremely powerful in motivating cooperative behavior. (2) (But also see Sparks et al. for failed replications)

This study also suggests that, while Fitzgerald may have meant the Dr. Eckleburg sign as a nod toward religion being supplanted by commerce, there is an alternate reading of the scene that focuses on the sign’s more direct impact on George Wilson. In several scenes throughout the novel, Wilson shows his willingness to acquiesce in the face of Tom’s bullying. Nick describes him as “spiritless” and “anemic” (29). It could be that when he says “God sees everything” he’s in fact addressing himself because he is tempted not to pursue justice—to let the crime go unpunished and thus be guilty himself of being a second-order free-rider. He doesn’t, after all, exert any great effort to find and kill Gatsby, and he kills himself immediately thereafter anyway.

Religion in Gatsby does, of course, go beyond some suggestive references to an empty placeholder. Nick ends the story with a reflection on how “Gatsby believed in the green light,” the light across the bay which he knew signaled Daisy’s presence in the mansion she lived in there. But for Gatsby it was also “the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther… And one fine morning—” (189). Earlier Nick had explained how Gatsby “talked a lot about the past and I gathered that he wanted to recover something, some idea of himself perhaps, that had gone into loving Daisy.” What that idea was becomes apparent in the scene describing Gatsby and Daisy’s first kiss, which occurred years prior to the events of the plot. “He knew that when he kissed this girl, and forever wed his unutterable visions to her perishable breath, his mind would never romp again like the mind of God… At his lips’ touch she blossomed for him like a flower and the incarnation was complete” (117). In place of some mind in the sky, the design Americans are encouraged to live by is one they have created for themselves. Unfortunately, just as there is no mind behind the eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg, the designs many people come up with for themselves are based on tragically faulty premises.

The replacement of religiously inspired moral principles with selfish economic and hierarchical calculations, which Dr. Eckleburg so perfectly represents, is what ultimately leads to all the disgraceful behavior Nick describes. He writes, “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and people and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess” (188). Game theorist and behavioral economist Robert Frank, whose earlier work greatly influenced William Flesch’s theories of narrative, has recently written about how the same social dynamics Fitzgerald lamented are in place again today. In The Darwin Economy, he describes what he calls an “expenditure cascade”:

The explosive growth of CEO pay in recent decades, for example, has led many executives to build larger and larger mansions. But those mansions have long since passed the point at which greater absolute size yields additional utility… Top earners build bigger mansions simply because they have more money. The middle class shows little evidence of being offended by that. On the contrary, many seem drawn to photo essays and TV programs about the lifestyles of the rich and famous. But the larger mansions of the rich shift the frame of reference that defines acceptable housing for the near-rich, who travel in many of the same social circles… So the near-rich build bigger, too, and that shifts the relevant framework for others just below them, and so on, all the way down the income scale. By 2007, the median new single-family house built in the United States had an area of more than 2,300 square feet, some 50 percent more than its counterpart from 1970. (61-2)

How exactly people are straining themselves to afford these houses would be a fascinating topic for Fitzgerald’s successors. But one thing is already abundantly clear: it’s not the CEOs who are cleaning up the mess.

Also read:

HOW TO GET KIDS TO READ LITERATURE WITHOUT MAKING THEM HATE IT

WHY THE CRITICS ARE GETTING LUHRMANN'S GREAT GATSBY SO WRONG

WHY SHAKESPEARE NAUSEATED DARWIN: A REVIEW OF KEITH OATLEY'S "SUCH STUFF AS DREAMS"

T.J. Eckleburg Sees Everything: The Great God-Gap in Gatsby part 1 of 2

So profound is humans’ concern for their reputations that they can even be nudged toward altruistic behaviors by the mere suggestion of invisible witnesses or the simplest representation of watching eyes. The billboard featuring Dr. Eckleburg’s eyes, however, holds no sway over George’s wife Myrtle, or the man she has an affair with. That this man, Tom Buchanan, has such little concern for his reputation—or that he simply feels entitled to exploit Myrtle—serves as an indictment of the social and economic inequality in the America of Fitzgerald’s day.

When George Wilson, in one of the most disturbing scenes in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic The Great Gatsby, tells his neighbor that “God sees everything” while staring disconsolately at the weathered advertisement of some long-ago optometrist named T.J. Eckleburg, his longing for a transcendent authority who will mete out justice on his behalf pulls at the hearts of readers who realize his plea will go unheard. Anthropologists and psychologists studying the human capacity for cooperation and altruism are coming to view religion as an important factor in our evolution. Since the cooperative are always at risk of being exploited by the selfish, mechanisms to enforce altruism had to be in place for any tendency to behave for the benefit of others to evolve. The most basic of these mechanisms is a constant awareness of our own and our neighbors’ reputations. Humans, research has shown, are far more tempted to behave selfishly when they believe it won’t harm their reputations—i.e. when they believe no witnesses are present.

So profound is humans’ concern for their reputations that they can even be nudged toward altruistic behaviors by the mere suggestion of invisible witnesses or the simplest representation of watching eyes. The billboard featuring Dr. Eckleburg’s eyes, however, holds no sway over George’s wife Myrtle, or the man she has an affair with. That this man, Tom Buchanan, has such little concern for his reputation—or that he simply feels entitled to exploit Myrtle—serves as an indictment of the social and economic inequality in the America of Fitzgerald’s day, which carved society into hierarchically arranged echelons and exposed the have-nots to the careless depredations of the haves.

Nick Carraway, the narrator, begins the story by recounting a lesson he learned from his father as part of his Midwestern upbringing. “Whenever you feel like criticizing anyone,” Nick’s father had told him, “just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had”(5). This piece of wisdom serves at least two purposes: it explains Nick’s self-proclaimed inclination to “reserve all judgments,” highlighting the severity of the wrongdoings which have prompted him to write the story; and it provides an ironic moral lens through which readers view the events of the plot. What is to be made, in light of Nick’s father’s reminder about unevenly parceled out advantages, of the crimes committed by wealthy characters like Tom and Daisy Buchanan?

The focus on morality notwithstanding, religion plays a scant, but surprising, role in The Great Gatsby. It first appears in a conversation between Nick and Catherine, the sister of Myrtle Wilson. Catherine explains to Nick that neither Tom nor Myrtle “can stand the person they’re married to” (37). To the obvious question of why they don’t simply leave their spouses, Catherine responds that it’s Daisy, Tom’s wife, who represents the sole obstacle to the lovers’ happiness. “She’s a Catholic,” Catherine says, “and they don’t believe in divorce” (38). However, Nick explains that “Daisy was not a Catholic,” and he goes on to admit, “I was a little shocked by the elaborateness of the lie.” The conversation takes place at a small gathering hosted by Tom and Myrtle in an apartment rented, it seems, for the sole purpose of giving the two a place to meet. Before Nick leaves the party, he witnesses an argument between the hosts over whether Myrtle has any right to utter Daisy’s name which culminates in Tom striking her and breaking her nose. Obviously, Tom doesn’t despise his wife as much as Myrtle does her husband. And the lie about Daisy’s religious compunctions serves simply to justify Tom’s refusal to leave her and facilitate his continued exploitation of Myrtle.

The only other scene in which a religious belief is asserted explicitly is the one featuring the conversation between George and his neighbor. It comes after Myrtle, whose dalliance had finally aroused her husband’s suspicion, has been struck by a car and killed. George, upon discovering that something had been going on behind his back, locked Myrtle in his garage, and it was when she escaped and ran out into the road to stop the car she thought Tom was driving that she got hit. As the dust from the accident settles—literally, since the garage and the stretch of road are situated in a “valley of ashes” created by the remnants of the coal powering the nearby city being dumped alongside the adjacent rail tracks—George is left alone with a fellow inhabitant of the valley, a man named Michaelis, who asks if he belongs to a church where there might a be a priest he can call to come comfort him. “Don’t belong to one,” George answers (165). He does, however, describe a religious belief of sorts to Michaelis. Having explained why he’d begun to suspect Myrtle was having an affair, George goes on to say, “I told her she might fool me but she couldn’t fool God. I took her to the window.” He walks to the window again as he’s telling the story to his neighbor. “I said, ‘God knows what you’ve been doing, everything you’ve been doing. You may fool me but you can’t fool God!’” (167). Michaelis, who is by now fearing for George’s sanity, notices something disturbing as he stands listening to this rant: “Standing behind him Michaelis saw with a shock that he was looking at the eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg which had just emerged pale and enormous from the dissolving night” (167). When George speaks again, repeating, “God sees everything,” Michaelis feels compelled to assure him, “That’s an advertisement” (167). Though when George first expresses the sentiment, part declaration, part plea, he was clearly thinking of Myrtle’s crime against him, when he repeats it he seems to be thinking of the driver’s crime against Myrtle. God may have seen it, but George takes it upon himself to deliver the punishment.

George Wilson’s turning to God for some moral accounting, despite his general lack of religious devotion, mirrors Nick Carraway’s efforts to settle the question of culpability, despite his own professed reluctance to judge, through the telling of this tragic story. Nick learns from Gatsby that it was in fact Daisy, with whom Gatsby has been carrying on an affair, who was behind the wheel of the car that killed Myrtle. But Gatsby, who was in the passenger seat, assures him it was an accident, not revenge for the affair Myrtle was carrying on with Daisy’s husband. Yet when George finally leaves his garage and turns to Tom to find out who owns the car that killed his wife, assuming it is the same man his wife was cheating on him with, Tom informs him the car belongs to Gatsby, leaving out the crucial fact that Gatsby never met Myrtle. George goes to Gatsby’s mansion, finds him in his pool, shoots and kills him, and then turns the gun on himself. Three people end up dead, Myrtle, George, and Gatsby. Despite their clear complicity, though, Tom and Daisy experience nary a repercussion beyond the natural grief of losing their lovers. Insofar as Nick believes the Buchanans’ perfect getaway is an intolerable injustice, he must realize he holds the power to implicate them, to damage their reputations, by writing and publishing his account of the incidents leading up to the deaths.

Evolutionary critic William Flesch sees our human passion for narrative as a manifestation of our obsession with our own and our fellow humans’ reputations, which evolved at least in part to keep track of each other’s propensities for moral behavior. In Comeuppance: Costly Signaling, Altruistic Punishment, and Other Biological Components of Fiction, Flesch lays out his attempt at solving what he calls “the puzzle of narrative interest,” by which he means the question of why people feel “anxiety on behalf of and about the motives, actions, and experiences of fictional characters” (7). He finds the key to solving this puzzle in a concept called “strong reciprocity,” whereby “the strong reciprocator punishes and rewards others for their behavior toward any member of the social group, and not just or primarily for their individual interactions with the reciprocator” (22). An example of this phenomenon takes place in the novel when the guests at Gatsby’s parties gossip and ardently debate about which of the rumors circling their host are true—particularly of interest is the one saying that “he killed a man” (48). Flesch cites reports from experiments demonstrating that in uneven exchanges, participants with no stake in the outcome are actually willing to incur some cost to themselves in an effort to enforce fairness (31-5). He then goes on to give a compelling account of how this tendency goes a long way toward an explanation of our human fascination with storytelling.

Flesch’s theory of narrative interest begins with models of the evolution of cooperation. For the first groups of human ancestors to evolve cooperative or altruistic traits, they would have had to solve what biologists and game theorists call “the free-rider problem.” Flesch explains:

Darwin himself had proposed a way for altruism to evolve through a mechanism of group selection. Groups with altruists do better as a group than groups without. But it was shown in the 1960s that, in fact, such groups would be too easily infiltrated or invaded by nonaltruists—that is, that group boundaries were too porous—to make group selection strong enough to overcome competition at the level of the individual or the gene. (5)