READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

The Upper Hand in Relationships

What began as an exercise in SEO (search engine optimization) became such a success it’s probably my most widely read piece of writing (somewhat to my chagrin). Apparently, my background in psychology and long history of dating equipped me with some helpful insight. Bottom line: stay away from people playing zero-sum games. And don’t give away too much too soon. You’ll have to read to find out more about what made this post so popular.

People perform some astoundingly clever maneuvers in pursuit of the upper hand in their romantic relationships, and some really stupid ones too. They try to make their partners jealous. They feign lack of interest. They pretend to have enjoyed wild success in the realm of dating throughout their personal histories, right up until the point at which they met their current partners. The edge in cleverness, however, is usually enjoyed by women—though you may be inclined to call it subtlety, or even deviousness.

Some of the most basic dominance strategies used in romantic relationships are based either on one partner wanting something more than the other, or on one partner being made to feel more insecure than the other. We all know couples whose routine revolves around the running joke that the man is constantly desperate for sex, which allows the woman to set the terms he must meet in order to get some. His greater desire for sex gives her the leverage to control him in other domains. I’ll never forget being nineteen and hearing a friend a few years older say of her husband, “Why would I want to have sex with him when he can’t even remember to take out the garbage?” Traditionally, men held the family purse strings, so they—assuming they or their families had money—could hold out the promise of things women wanted more. Of course, some men still do this, giving their wives little reminders of how hard they work to provide financial stability, or dropping hints of their extravagant lifestyles to attract prospective dates.

You can also get the upper hand on someone by taking advantage of his or her insecurities. (If that fails, you can try producing some.) Women tend to be the most vulnerable to such tactics at the moment of choice, wanting their features and graces and wiles to make them more desirable than any other woman prospective partners are likely to see. The woman who gets passed up in favor of another goes home devastated, likely lamenting the crass superficiality of our culture.

Most of us probably know a man or two who, deliberately or not, manages to keep his girlfriend or wife in constant doubt when it comes to her ability to keep his attention. These are the guys who can’t control their wandering eyes, or who let slip offhand innuendos about incremental weight gain. Perversely, many women respond by expending greater effort to win his attention and his approval.

Men tend to be the most vulnerable just after sex, in the Was-it-good-for-you moments. If you found yourself seething at some remembrance of masculine insensitivity reading the last paragraph, I recommend a casual survey of your male friends in which you ask them how many of their past partners at some point compared them negatively to some other man, or men, they had been with prior to the relationship. The idea that the woman is settling for a man who fails to satisfy her as others have plays into the narrative that he wants sex more—and that he must strive to please her outside the bedroom.

If you can put your finger on your partner’s insecurities, you can control him or her by tossing out reassurances like food pellets to a trained animal. The alternative would be for a man to be openly bowled over by a woman’s looks, or for a woman to express in earnest her enthusiasm for a man’s sexual performances. These options, since they disarm, can be even more seductive; they can be tactics in their own right—but we’re talking next-level expertise here so it’s not something you’ll see very often.

I give the edge to women when it comes to subtly attaining the upper hand in relationships because I routinely see them using a third strategy they seem to have exclusive rights to. Being the less interested party, or the most secure and reassuring party, can work wonders, but for turning proud people into sycophants nothing seems to work quite as well as a good old-fashioned guilt-trip.

To understand how guilt-trips work, just consider the biggest example in history: Jesus died on the cross for your sins, and therefore you owe your life to Jesus. The illogic of this idea is manifold, but I don’t need to stress how many people it has seduced into a lifetime of obedience to the church. The basic dynamic is one of reciprocation: because one partner in a relationship has harmed the other, the harmer owes the harmed some commensurate sacrifice.

I’m probably not the only one who’s witnessed a woman catching on to her man’s infidelity and responding almost gleefully—now she has him. In the first instance of this I watched play out, the woman, in my opinion, bore some responsibility for her husband’s turning elsewhere for love. She was brutal to him. And she believed his guilt would only cement her ascendancy. Fortunately, they both realized about that time she must not really love him and they divorced.

But the guilt need not be tied to anything as substantive as cheating. Our puritanical Christian tradition has joined forces in America with radical feminism to birth a bastard lovechild we encounter in the form of a groundless conviction that sex is somehow inherently harmful—especially to females. Women are encouraged to carry with them stories of the traumas they’ve suffered at the hands of monstrous men. And, since men are of a tribe, a pseudo-logic similar to the Christian idea of collective guilt comes into play. Whenever a man courts a woman steeped in this tradition, he is put on early notice—you’re suspect; I’m a trauma survivor; you need to be extra nice, i.e. submissive.

It’s this idea of trauma, which can be attributed mostly to Freud, that can really make a relationship, and life, fraught and intolerably treacherous. Behaviors that would otherwise be thought inconsiderate or rude—a hurtful word, a wandering eye—are instead taken as malicious attempts to cause lasting harm. But the most troubling thing about psychological trauma is that belief in it is its own proof, even as it implicates a guilty party who therefore has no way to establish his innocence.

Over the course of several paragraphs, we’ve gone from amusing but nonetheless real struggles many couples get caught up in to some that are just downright scary. The good news is that there is a subset of people who don’t see relationships as zero-sum games. (Zero-sum is a game theory term for interactions in which every gain for one party is a loss for the other. Non zero-sum games are those in which cooperation can lead to mutual benefits.) The bad news is that they can be hard to find.

There are a couple of things you can do now though that will help you avoid chess match relationships—or minimize the machinations in your current romance. First, ask yourself what dominance tactics you tend to rely on. Be honest with yourself. Recognizing your bad habits is the first step toward breaking them. And remember, the question isn’t whether you use tactics to try to get the upper hand; it’s which ones you use how often?

The second thing you can do is cultivate the habit and the mutual attitude of what’s good for one is good for the other. Relationship researcher Arthur Aron says that celebrating your partner’s successes is one of the most important things you can do in a relationship. “That’s even more important,” he says, “than supporting him or her when things go bad.” Watch out for zero-sum responses, in yourself and in your partner. And beware of zero-summers in the realm of dating.

Ladies, you know the guys who seem vaguely resentful of the power you have over them by dint of your good looks and social graces. And, guys, you know the women who make you feel vaguely guilty and set-upon every time you talk to them. The best thing to do is stay away.

But you may be tempted, once you realize a dominance tactic is being used on you, to perform some kind of countermove. It’s one of my personal failings to be too easily provoked into these types of exchanges. It is a dangerous indulgence.

Also read

Anti-Charm - Its Powers and Perils

What's Wrong with The Darwin Economy?

Antler size places each male elk in a relative position; in their competition for mates, absolute size means nothing. So natural selection—here operating in place of Smith’s invisible hand—ensures that the bull with the largest antlers reproduces and that antler size accordingly undergoes runaway growth. But what’s good for mate competition is bad for a poor elk trying to escape from a pack of hungry wolves.

I can easily imagine a conservative catching a glimpse of the cover of Robert Frank’s new book and having his interest piqued. The title, The Darwin Economy, evokes that famous formulation, “survival of the fittest,” but in the context of markets, which suggests a perspective well in keeping with the anti-government principles republicans and libertarians hold dear. The subtitle, Liberty, Competition, and the Common Good, further facilitates the judgment of the book by its cover as another in the long tradition of paeans to the glorious workings of unregulated markets.

The Darwin Economy puts forth an argument that most readers, even those who keep apace of the news and have a smidgen of background in economics, have probably never heard, namely that the divergence between individual and collective interests, which Adam Smith famously suggested gets subsumed into market forces which inevitably redound to the common good, in fact leads predictably to outcomes that are detrimental to everyone involved. His chief example is a hypothetical business that can either pay to have guards installed to make its power saws safer for workers to operate or leave the saws as they are and pay the workers more for taking on the added risk.

This is exactly the type of scenario libertarians love. What right does government have to force businesses in this industry to install the guards? Governmental controls end up curtailing the freedom of workers to choose whether to work for a company with better safety mechanisms or one that offers better pay. It robs citizens of the right to steer their own lives and puts decisions in the hands of those dreaded Washington bureaucrats. “The implication,” Frank writes, “is that, for well-informed workers at least, Adam Smith’s invisible hand would provide the best combinations of wages and safety even without regulation” (41).

Frank challenges the invisible hand doctrine by demonstrating that it fails to consider the full range of the ramifications of market competition, most notably the importance of relative position. But

The Darwin Economy offers no support for the popular liberal narrative about exploitative CEOs. Frank writes: “many of the explanations offered by those who have denounced market outcomes from the left fail the no-cash-on-the-table test. These critics, for example, often claim that we must regulate workplace safety because workers would otherwise be exploited by powerful economic elites” (36). But owners and managers are motivated by profits, not by some perverse desire to see their workers harmed.

Mobility isn’t perfect, but people change jobs far more frequently than in the past. And even when firms know that most of their employees are unlikely to move, some do move and others eventually retire or die. So employers must maintain their ability to attract a steady flow of new applicants, which means they must nurture their reputations. There are few secrets in the information age. A firm that exploits its workers will eventually experience serious hiring difficulties (38).

This is what Frank means by the no-cash-on-the-table test: companies who maintain a reputation for being good to their people attract more talented applicants, thus increasing productivity, thus increasing profits. There’s no incentive to exploit workers just for the sake of exploiting them, as many liberals seem to suggest.

What makes Frank convincing, and what makes him something other than another liberal in the established line-up, is that he’s perfectly aware of the beneficial workings of the free market, as far as they go. He bases his policy analyses on a combination of John Stuart Mill’s harm principle—whereby the government only has the right to regulate the actions of a citizen if those actions are harmful to other citizens—and Ronald Coase’s insight that government solutions to harmful actions should mimic the arrangements that the key players would arrive at in the absence of any barriers to negotiation. “Before Coase,” Frank writes,

it was common for policy discussions of activities that cause harm to others to be couched in terms of perpetrators and victims. A factory that created noise was a perpetrator, and an adjacent physician whose practice suffered as a result was a victim. Coase’s insight was that externalities like noise or smoke are purely reciprocal phenomena. The factory’s noise harms the doctor, yes; but to invoke the doctor’s injury as grounds for prohibiting the noise would harm the factory owner (87).

This is a far cry from the naïve thinking of some liberal do-gooder. Frank, following Coase, goes on to suggest that what would formerly have been referred to as the victim should foot the bill for a remedy to the sound pollution if it’s cheaper for him than for the factory. At one point, Frank even gets some digs in on Ralph Nader for his misguided attempts to protect the poor from the option of accepting payments for seats when their flights are overbooked.

Though he may be using the same market logic as libertarian economists, he nevertheless arrives at very different conclusions vis-à-vis the role and advisability of government intervention. Whether you accept his conclusions or not hinges on how convincing you find his thinking about the role of relative position. Getting back to the workplace safety issue, we might follow conventional economic theory and apply absolute values to the guards protecting workers from getting injured by saws. If the value of the added safety to an individual worker exceeds the dollar amount increase he or she can expect to get at a company without the guards, that worker should of course work at the safer company. Unfortunately, considerations of safety are abstract, and they force us to think in ways we tend not to be good at. And there are other, more immediate and concrete considerations that take precedence over most people’s desire for safety.

If working at the company without the guards on the saws increases your income enough for you to move to a house in a better school district, thus affording your children a better education, then the calculations of the absolute worth of the guards’ added safety go treacherously awry. Frank explains

the invisible-hand narrative assumes that extra income is valued only for the additional absolute consumption it supports. A higher wage, however, also confers a second benefit for certain (and right away) that safety only provides in the rare cases when the guard is what keeps the careless hand from the blade—the ability to consume more relative to others. That fact is nowhere more important than in the case of parents’ desires to send their children to the best possible schools…. And because school quality is an inherently relative concept, when others also trade safety for higher wages, no one will move forward in relative terms. They’d succeed only in bidding up the prices of houses in better school districts (40).

Housing prices go up. Kids end up with no educational advantage. And workers are less safe. But any individual who opted to work at the safer company for less pay would still have to settle for an inferior school district. This is a collective action problem, so individuals are trapped, which of course is something libertarians are especially eager to avoid.

Frank draws an analogy with many of the bizarre products of what Darwin called sexual selection, most notably those bull elk battling it out on the cover of the book. Antler size places each male elk in a relative position; in their competition for mates, absolute size means nothing. So natural selection—here operating in place of Smith’s invisible hand—ensures that the bull with the largest antlers reproduces and that antler size accordingly undergoes runaway growth. But what’s good for mate competition is bad for a poor elk trying to escape from a pack of hungry wolves. If there were some way for a collective agreement to be negotiated that forced every last bull elk to reduce the size of his antlers by half, none would object, because they would all benefit. This is the case as well with the workers' decision to regulate safety guards on saws. And Frank gives several other examples, both in the animal kingdom and in the realms of human interactions.

I’m simply not qualified to assess Frank’s proposals under the Coase principle to tax behaviors that have harmful externalities, like the production of CO2, including a progressive tax on consumption. But I can’t see any way around imposing something that achieves the same goals at some point in the near future.

My main criticism of The Darwin Economy is that the first chapter casual conservative readers will find once they’ve cracked the alluring cover is the least interesting of the book because it lists the standard litany of liberal complaints. A book as cogent and lucid as this one, a book which manages to take on abstract principles and complex scenarios while still being riveting, a book which contributes something truly refreshing and original to the exhausted and exhausting debates between liberals and conservatives, should do everything humanly possible to avoid being labeled into oblivion. Alas, the publishers and book-sellers would never allow a difficult-to-place book to grace their shelves or online inventories.

Also read:

THE IMP OF THE UNDERGROUND AND THE LITERATURE OF LOW STATUS

More of a Near Miss--Response to "Collision"

The documentary Collision is an attempt at irony. The title is spelled on the box with a bloody slash for the i coming in the middle of the word. The film opens with hard rock music and Christopher Hitchens dropping the gauntlet: "One of us will have to admit he's wrong. And I think it should be him." There are jerky closeups and dramatic pullaways. The whole thing is made to resemble one of those pre-event commercials on pay-per-view for boxing matches or UFC's.

The documentary Collision is an attempt at irony. The title is spelled on the box with a bloody slash for the i coming in the middle of the word. The film opens with hard rock music and Christopher Hitchens dropping the gauntlet: "One of us will have to admit he's wrong. And I think it should be him." There are jerky closeups and dramatic pullaways. The whole thing is made to resemble one of those pre-event commercials on pay-per-view for boxing matches or UFC's.The big surprise, which I don't think I'm ruining, is that evangelical Christian Douglas Wilson and anti-theist Christopher Hitchens--even in the midst of their heated disagreement--seem to like and respect each other. At several points they stop debating and simply chat with one another. They even trade Wodehouse quotes (and here I thought you had to be English to appreciate that humor). Some of the best scenes have the two men disagreeing without any detectable bitterness, over drinks in a bar, as they ride side by side in car, and each even giving signs of being genuinely curious about what the other is saying. All this bonhomie takes place despite the fact that neither changes his position at all over the course of their book tour.

I guess for some this may come as a surprise, but I've been arguing religion and science and politics with people I like, or even love, since I was in my early teens. One of the things that got me excited about the movie was that my oldest brother, a cancer biologist whose professed Christianity I suspect is a matter of marital expediency (just kidding), once floated the idea of collaborating on a book similar to Wilson and Hitchens's. So I was more disappointed than pleasantly surprised that the film focused more on the two men's mutual respect than on the substance of the debate.

There were some parts of the argument that came through though. The debate wasn't over whether God exists but whether belief in him is beneficial to the world. Either the director or the editors seemed intent on making the outcome an even wash. Wilson took on Hitchens's position that morality is innate, based on an evolutionary need for "human solidarity," by pointing out, validly, that so is immorality and violence. He suggested that Hitchens's own morality was in fact derived from Christianity, even though Hitchens refuses to acknowledge as much. If both morality and its opposite come from human nature, Wilson argues, then you need a third force to compel you in one direction over the other. Hitchens, if he ever answered this point, wasn't shown doing so in the documentary. He does point out, though, that Christianity hasn't been any better historically at restricting human nature to acting on behalf of its better angels.

Wilson's argument is fundamentally postmodern. He explains at one point that he thinks rationalists giving reasons for their believing what they do is no different from him quoting a Bible verse to explain his belief in the Bible. All epistemologies are circular. None are to be privileged. This is nonsense. And it would have been nice to see Hitchens bring him to task for it. For one thing, the argument is purely negative--it attempts to undermine rationalism but offers no positive arguments on behalf of Christianity. To the degree that it effectively casts doubt on nonreligious thinking, it cast the same amount of doubt on religion. For another, the analogy strains itself to the point of absurdity. Reason supporting reason is a whole different animal from the Bible supporting the Bible for the same reason that a statement arrived at by deduction is different from a statement made at random. Two plus two equals four isn't the same as there's an invisible being in the sky and he's pissed.

Of course, two plus two equals four is tautological. It's circular. But science isn't based on rationalism alone; it's rationalism cross-referenced with empiricism. If Wilson's postmodern arguments had any validity (and they don't) they still don't provide him with any basis for being a Christian as opposed to an atheist as opposed to a Muslim as opposed to a drag queen. But science offers a standard of truth.

Wilson's other argument, that you need some third factor beyond good instincts and bad instincts to be moral, is equally lame. Necessity doesn't establish validity. As one witness to the debate in a bar points out, an argument from practicality doesn't serve to prove a position is true. What I wish Hitchens had pointed out, though, is that the third factor need not be divine authority. It can just as easily be empathy. And what about culture? What about human intentionality? Can't we look around, assess the state of the world, realize our dependence on other humans in an increasingly global society, and decide to be moral? I'm a moral being because I was born capable of empathy, and because I subscribe to Enlightenment principles of expanding that empathy and affording everyone on Earth a set of fundamental human rights. And, yes, I think the weight of the evidence suggests that religion, while it serves to foster in-group cooperation, also inspires tribal animosity and war. It needs to be done away with.

One last note: Hitchens tries to illustrate our natural impulse toward moral behavior by describing an assault on a pregnant woman. "Who wouldn't be appalled?" Wilson replies, "Planned Parenthood." I thought Hitchens of all people could be counted on to denounce such an outrage. Instead, he limply says, "Don't be flippant," then stands idly, mutely, by as Wilson explains how serious he is. It's a perfect demonstration of Hitchens's correctness in arguing that Christianity perverts morality that a man as intelligent as Wilson doesn't see that comparing a pregnant woman being thrown down and kicked in the stomach to abortion is akin to comparing violent rape to consensual sex. He ought to be ashamed--but won't ever be. I think Hitchens ought to be ashamed for letting him say it unchallenged (unless the challenge was edited out).

How to Read Stories--You're probably doing it wrong

Your efforts to place each part into the context of the whole will, over time, as you read more stories, give you a finer appreciation for the strategies writers use to construct their work, one scene or one section at a time. And as you try to anticipate the parts to come from the parts you’ve read you will be training your mind to notice patterns, laying down templates for how to accomplish the types of effects—surprise, emotional resonance, lyricism, profundity—the author has accomplished.

There are whole books out there about how to read like a professor or a writer, or how to speed-read and still remember every word. For the most part, you can discard all of them. Studies have shown speed readers are frauds—the faster they read the less they comprehend and remember. The professors suggest applying the wacky theories they use to write their scholarly articles, theories which serve to cast readers out of the story into some abstract realm of symbols, psychological forces, or politics. I find the endeavor offensive.

Writers writing about how to read like a writer are operating on good faith. They just tend to be a bit deluded. Literature is very much like a magic trick, but of course it’s not real magic. They like to encourage people to stand in awe of great works and great passages—something I frankly don’t need any encouragement to do (what is it about the end of “Mr. Sammler’s Planet”?) But to get to those mystical passages you have to read a lot of workaday prose, even in the work of the most lyrical and crafty writers. Awe simply can’t be used as a reading strategy.

Good fiction is like a magic trick because it’s constructed of small parts that our minds can’t help responding to holistically. We read a few lines and all the sudden we have a person in mind; after a few pages we find ourselves caring about what happens to this person. Writers often avoid talking about the trick and the methods and strategies that go into it because they’re afraid once the mystery is gone the trick will cease to convince. But even good magicians will tell you well performed routines frequently astonish even the one performing them. Focusing on the parts does not diminish appreciation for the whole.

The way to read a piece of fiction is to use the information you've already read in order to anticipate what will happen next. Most contemporary stories are divided into several sections, which offer readers the opportunity to pause after each, reflecting how it may fit into the whole of the work. The author had a purpose in including each section: furthering the plot, revealing the character’s personality, developing a theme, or playing with perspective. Practice posing the questions to yourself at the end of each section, what has the author just done, and what does it suggests she’ll likely do in sections to come.

In the early sections, questions will probably be general: What type of story is this? What type of characters are these? But by the time you reach about the two/thirds point they will be much more specific: What’s the author going to do with this character? How is this tension going to be resolved? Efforts to classify and anticipate the elements of the story will, if nothing else, lead to greater engagement with it. Every new character should be memorized—even if doing so requires a mnemonic (practice coming up with one on the fly).

The larger goal, though, is a better understanding of how the type of fiction you read works. Your efforts to place each part into the context of the whole will, over time, as you read more stories, give you a finer appreciation for the strategies writers use to construct their work, one scene or one section at a time. And as you try to anticipate the parts to come from the parts you’ve read you will be training your mind to notice patterns, laying down templates for how to accomplish the types of effects—surprise, emotional resonance, lyricism, profundity—the author has accomplished.

By trying to get ahead of the author, as it were, you won’t be learning to simply reproduce the same effects. By internalizing the strategies, making them automatic, you’ll be freeing up your conscious mind for new flights of creative re-working. You’ll be using the more skilled author’s work to bootstrap your own skill level. But once you’ve accomplished this there’ll be nothing stopping you from taking your own writing to the next level. Anticipation makes reading a challenge in real time—like a video game. And games can be conquered.

Finally, if a story moves you strongly, re-read it immediately. And then put it in a stack for future re-reading.

Also read:

PUTTING DOWN THE PEN: HOW SCHOOL TEACHES US THE WORST POSSIBLE WAY TO READ LITERATURE

Magic, Fiction, and the Illusion of Free Will part 2

Part 2 of my review of Sleights of Mind

Johansson and Hall, in their studies of choice blindness, are building on a tradition harking to the lab of a neurophysiologist working in the 1970’s in San Francisco. Benjamin Libet, in an era before fMRIs, used the brain scanning devices available to him, EEG and EGM (or electromyograph, which measures electrical activity in muscles), to pinpoint when his subjects were physically set in motion by a decision. Macknik and Martinez-Conde explain “Libet found that participants had the conscious sense of willing the movement about 300 milliseconds after the onset of the muscle activity. Moreover, the EEG showed that neurons in the part of their motor cortex where movements are planned became active a full second before any movement could be measured” (180). We all go about our business blithely assured that we decide to do something and then, subsequently, we act on our decision. But in reality our choices tend to be made outside of our conscious awareness, based on mechanisms our minds have no conscious access to, and it’s our justifications for those choices that really come second in the sequence of events. We don’t even know that we’re confabulating, just making stuff up on the fly to explain ourselves, that we’re not being honest. Our confabulations fool us as much as they fool everyone else.

In the decades following Libet’s work, more sophisticated scanners have put the time lapse between when our brains make decisions and when we feel as though our conscious minds have made them as high as seven seconds. That means people who are good at reading facial expressions and body language can often tell what choices we’ll make before we make them. Magicians and mentalists delight in exploiting this quirk of human cognition. Then their marks weave the clever tricksters into their confabulations—attributing to them supernatural powers. Reading this section of Sleights of Mind sent me to my bookshelf for Sack’s The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat because I recalled the story of a patient with Korsakov’s Syndrome who had a gift for rapid confabulation. In a chapter titled “A Matter of Identity,” Sacks narrates his meeting with a man he calls Mr. Thompson, who first treats him as if he’s a customer at the delicatessen where he worked, then shifts to believing the doctor is the butcher next door, then it’s a mechanic, then it’s a doctor—another doctor. In fact, due to neurological damage caused by a fever, Mr. Thompson can’t know who Sacks is; he can’t form moment-to-moment memories or any sense of where he is in time or space. He’s literally disconnected from the world. But his mind has gone into overdrive trying to fill in the missing information. Sacks writes,

Abysses of amnesia continually opened beneath him, but he would bridge them, nimbly, by fluent confabulations and fictions of all kinds. For him they were not fictions, but how he suddenly saw, or interpreted, the world (109).

But it’s not Mr. Thompson’s bizarre experience that’s noteworthy; it’s how that experience illuminates our own mundane existence that’s unsettling. And Sacks goes on to explain that it’s not just the setting and the people he encounters that Mr. Thompson had to come up with stories for. He’d also lost the sense of himself.

“Such a frenzy may call forth quite brilliant powers of invention and fancy—a veritable confabulatory genius—for such a patient must literally make himself (and his world) up every moment. We have, each of us, a life-story, an inner narrative—whose continuity, whose sense, is our lives. It might be said that each of us constructs, and lives, a ‘narrative’, and that this narrative is us, our identities” (110).

Mr. Thompson’s confabulatory muscles may be more taxed than most of ours, but we all have them; we all rely on them to make sense of the world and to place ourselves within it. When people with severe epilepsy have the two hemispheres of their brains surgically separated to limit the damage of their seizures, and subsequently have a message delivered to their right hemisphere, they cannot tell you what that message was because language resides in the left hemisphere. But they can and do respond to those messages. When Michael Gazzaniga presented split-brain patients’ right hemispheres with commands to walk or to laugh, they either got up and started walking or began to laugh. When asked why, even though they couldn’t know the true reason, they came up with explanations. “I’m getting a coke,” or “It’s funny how you scientists come up with new tests every week” (Pinker How the Mind Works, pg. 422). G.H. Estabrooks reports that people acting on posthypnotic suggestions, who are likewise unaware they’ve been told by someone else to do something, show the same remarkable capacity for confabulation. He describes an elaborate series of ridiculous behaviors, like putting a lampshade on someone’s head and kneeling before them, that the hypnotized subjects have no problem explaining. “It sounds queer but it’s just a little experiment in psychology,” one man said, oblivious of the irony (Tim Wilson Strangers to Ourselvespg. 95).

Reading Sleights of Mind and recalling these other books on neuroscience, I have this sense that I, along with everyone else, am walking around in a black fog into which my mind projects a three-dimensional film. We never know whether we’re seeing through the fog or whether we’re simply watching the movie projected by our mind. It should pose little difficulty coming up with a story plot, in the conventional sense, that simultaneously surprises and fulfills expectations—we’re doing it constantly. The challenge must be to do it in a way creative enough to stand out amid the welter of competition posed by run-of-the-mill confabulations. Could a story turn on the exposure of the mechanism behind the illusion of free will? Isn’t there a plot somewhere in the discrepancy between our sense that we’re in the driver’s seat, as it were, and the reality that we’re really surfing a wave, propelled along with a tiny bit of discretion regarding what direction we take, every big move potentially spectacular and at the same time potentially catastrophic?

Until I work that out, I’ll turn briefly to another mystery—because I can’t help making a political point and then a humanistic one. The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat is, pardon the pun, old hat to neuroscientists. And presumably magicians know something about the trick behind our conviction that we have free will. Pen and Teller in particular, because they draw inspiration from The Amaz!ng Randi, a celebrity in the world of skeptics, ought to be well aware of the fact that free will is an illusion. (All three magicians feature prominently in Sleights of Mind.) So how the hell can these guys serve as fellows in the Cato Institute, a front for fossil fuel industry propaganda pretending to be a conservative policy research? (For that matter, how can research have a political leaning?) Self-determination and personal responsibility, the last time I checked, were the foundations of conservative economics. How can Pen and Teller support politics based on what they know is an illusion?

Macknik and Martinez-Conde cite research in an endnote to Sleights of Mind that may amount to an explanation. When Kathleen Vohs and Jonathan Schooler prompted participants in what they said was a test of mental arithmetic with a passage from Francis Crick about how free will and identity arise from the mechanistic interworkings of chemicals and biomatter, they were much more likely to cheat than participants prompted with more neutral passages. Macknik and Martinez-Conde write, “One of the more interesting findings in the free will literature is that when people believe, or are led to believe, that free will is an illusion, they may become more antisocial” (272). Though in Pen and Teller’s case a better word than antisocial is probably contemptuous. How could you not think less and less of your fellow man when you make your living every day making fools of him? And if the divine light of every soul is really nothing more than a material spark why should we as a society go out of our way to medicate and educate those whose powers of perception and self-determination don’t even make for a good illusion?

For humanists, the question becomes, how can avoid this tendency toward antisocial attitudes and contempt while still embracing the science that has lifted our species out of darkness? For one thing, we must acknowledge to ourselves that if we see farther, it’s not because we’re inherently better but because of the shoulders on which we’re standing. While it is true that self-determination becomes a silly notion in light of the porousness of what we call the self, it is undeniable that some of us have more options and better influences than others. Sacks is more eloquent than anyone in expressing how the only thing separating neurologist from patient is misfortune. We can think the same way about what separates magicians from audience, or the rich from the poor. When we encounter an individual we’re capable of tricking, we can consider all the mishaps that might have befallen us and left us at the mercy of that individual. It is our capacity for such considerations that lies at the heart of our humanity. It is also what lies at the heart of our passion for the surprising and inevitable stories that only humans tell, even or especially the ones about ourselves we tell to ourselves.

(Pass the blunt.)

Also read:

OLIVER SACKS’S GRAPHOPHILIA AND OTHER COMPENSATIONS FOR A LIFE LIVED “ON THE MOVE”

And:

THE SOUL OF THE SKEPTIC: WHAT PRECISELY IS SAM HARRIS WAKING UP FROM?

And:

THE SELF-TRANSCENDENCE PRICE TAG: A REVIEW OF ALEX STONE'S FOOLING HOUDINI

Magic, Fiction, and the Illusion of Free Will part 1 of 2

It’s nothing new for people with a modicum of familiarity with psychology that there’s an illusory aspect to all our perceptions, but in reality it would be more accurate to say there’s a slight perceptual aspect to all our illusions. And one of those illusions is our sense of ourselves.

E.M. Forster famously wrote in his book Aspects of the Novel that what marks a plot resolution as gratifying is that it is both surprising and seemingly inevitable. Many have noted the similarity of this element of storytelling to riddles and magic tricks. “It’s no accident,” William Flesch writes in Comeuppance, “that so many stories revolve around riddles and their solutions” (133). Alfred Hitchcock put it this way: “Tell the audience what you’re going to do and make them wonder how.” In an ever-more competitive fiction market, all the lyrical prose and sympathy-inspiring characterization a brilliant mind can muster will be for naught if the author can’t pose a good riddle or perform some eye-popping magic.

Neuroscientist Stephen L. Macnick and his wife Susana Martinez-Conde turned to magicians as an experiment in thinking outside the box, hoping to glean insights into how the mind works from those following a tradition which takes advantage of its shortcuts and blind spots. The book that came of this collaboration, Sleights of Mind: What the Neuroscience of Magic Reveals about our Everyday Deceptions, is itself both surprising and seemingly inevitable (the website for the book). What a perfect blend of methods and traditions in the service of illuminating the mysteries of human perception and cognition. The book begins somewhat mundanely, with descriptions of magic tricks and how they’re done interspersed with sections on basic neuroscience. Readers of Skeptic Magazine or any of the works in the skeptical tradition will likely find the opening chapters hum-drum. But the sections have a cumulative effect.

The hook point for me was the fifth chapter, “The Gorilla in Your Midst,” which takes its title from the famous experiment conducted by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris in which participants are asked to watch a video of a group of people passing a basketball around and count the number of passes. A large portion of the participants are so engrossed in the task of counting that they miss a person walking onto the scene in a gorilla costume, who moves to the center of the screen, pounds on his chest, and then walks off camera. A subsequent study by Daniel Memmert tracked people’s eyes while they were watching the video and found that their failure to notice the gorilla wasn’t attributable to the focus of their gaze. Their eyes were directly on it. The failure to notice was a matter of higher-order brain processes: they weren’t looking for a gorilla, so they didn’t see it, even though their eyes were on it. Macnick and Martinez-Conde like to show the video to their students and ask the ones who do manage to notice the gorilla how many times the ball was passed. They never get the right answer. Of course, magicians exploit this limitation in our attention all the time. But we don’t have to go to a magic show to be exploited—we have marketers, PR specialists, the entertainment industry.

At the very least, I hoped Sleights of Mind would be a useful compendium of neuroscience concepts—a refresher course—along with some basic magic tricks that might help make the abstract theories more intuitive. At best, I hoped to glean some insight into how to arrange a sequence of events to achieve that surprising and inevitable effect in the plots of my stories. Some of the tricks might even inspire a plot twist or two. The lesser hope has been gratified spectacularly. It’s too soon to assess whether the greater one will be satisfied. But the book has impressed me on another front I hadn’t anticipated. Having just finished the ninth of twelve chapters, I’m left both disturbed and exhilarated in a way similar to how you feel reading the best of Oliver Sacks or Steven Pinker. There’s some weird shit going on in your brain behind the scenes of the normal stuff you experience in your mind. It’s nothing new for people with a modicum of familiarity with psychology that there’s an illusory aspect to all our perceptions, but in reality it would be more accurate to say there’s a slight perceptual aspect to all our illusions. And one of those illusions is our sense of ourselves.

I found myself wanting to scan the entire seventh chapter, “The Indian Rope Trick,” so I could send a pdf file to everyone I know. It might be the best summation I’ve read of all the ways we overestimate the power of our memories. So many people you talk to express an unwillingness to accept well established findings in psychology and other fields of science because the data don’t mesh with their experiences. Of course, we only have access to our experiences through memory. What those who put experience before science don’t realize is that memories aren’t anything like direct recordings of events; they’re bricolages of impressions laid down prior to the experience, a scant few actual details, and several impressions received well afterward. Your knowledge doesn’t arise from your experiences; your experiences arise from your knowledge. The authors write:

As the memory plays out in your mind, you may have the strong impression that it’s a high-fidelity record, but only a few of its contents are truly accurate. The rest of it is a bunch of props, backdrops, casting extras, and stock footage your mind furnishes on the fly in an unconscious process known as confabulation (119).

The authors go on to explore how confabulation creates the illusion of free will in the ninth chapter, “May the Force be with You.” Petter Johansson and Lars Hall discovered a phenomenon they call “choice blindness” by presenting participants in an experiment with photographs of two women of about equal attractiveness and asking them to choose which one they preferred. In a brilliant mesh of magic with science, the researchers then passed the picture over to the participant and asked him or her to explain their choice—only they used sleight of hand to switch the pictures. Most of them didn’t notice, and they went on to explain why they chose the woman in the picture that they had in fact rejected. The explanations got pretty elaborate too.

Eric Harris: Antisocial Aggressor or Narcissistic Avenger?

Conventional wisdom after the Columbine shooting was that the perpetrators had lashed out after being bullied. They were supposed to have low self-esteem and represented the dangers of letting kids go about feeling bad about themselves. But is it possible at least one of the two was in fact a narcissist? Eric Harris definitely had some fantasies of otherworldly grandeur.

Coincident with my writing a paper defending Gabriel Conroy in James Joyce’s story “The Dead” from charges of narcissism leveled by Lacanian critics, my then girlfriend was preparing a presentation on the Columbine shooter Eric Harris which had her trying to determine whether he would have better fit the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for Narcissistic or for Antisocial Personality Disorder. Everything about Harris screamed narcissist, but there was a deal-breaker for the diagnosis: people who hold themselves in astronomical esteem seem unlikely candidates for suicide, and Harris turned his gun on himself in culmination of his murder spree.

Clinical diagnoses are mere descriptive categorizations which don’t in any way explain behavior; at best, they may pave the way for explanations by delineating the phenomenon to be explained. Yet the nature of Harris’s thinking about himself has important implications for our understanding of other types of violence. Was he incapable of empathizing with others, unable to see and unwilling to treat them as feeling, sovereign beings, in keeping with an antisocial diagnosis? Or did he instead believe himself to be so superior to his peers that they simply didn’t merit sympathy or recognition, suggesting narcissism? His infamous journals suggest pretty unequivocally that the latter was the case. But again we must ask if a real narcissist would kill himself?

This seeming paradox was brought to my attention again this week as I was reading 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology: Shattering Widespread Misconceptions about Human Behavior (about which I will very likely be writing more here). Myth #33 is that “Low Self-Esteem Is a Major Cause of Psychological Problems” (162). The authors make use of the common misconception that the two boys responsible for the shootings were meek and shy and got constantly picked on until their anger boiled over into violence. (It turns out the boiling-over metaphor is wrong too, as explained under Myth #30: “It’s Better to Express Anger to Others than to Hold It in.”) The boys were indeed teased and taunted, but the experience didn’t seem to lower their view of themselves. “Instead,” the authors write, “Harris and Klebold’s high self-esteem may have led them to perceive the taunts of their classmates as threats to their inflated sense of self-worth, motivating them to seek revenge” (165).

Narcissists, they explain, “believe themselves deserving of special privileges” or entitlements. “When confronted with a challenge to their perceived worth, or what clinical psychologists term a ‘narcissistic injury,’ they’re liable to lash out at others” (165). We usually think of school shootings as random acts of violence, but maybe the Columbine massacre wasn’t exactly random. It may rather have been a natural response to perceived offenses—just one that went atrociously beyond the realm of what anyone would consider fair. If what Harris did on that day in April of 1999 was not an act of aggression but one of revenge, it may be useful to consider it in terms of costly punishment, a special instance of costly signaling.

The strength of a costly signal is commensurate with that cost, so Harris’s willingness both to kill and to die might have been his way of insisting that the offense he was punishing was deathly serious. What the authors of 50 Great Myths argue is that the perceived crime consisted of his classmates not properly recognizing and deferring to his superiority. Instead of contradicting the idea that Harris held himself in great esteem then, his readiness to die for the sake of his message demonstrates just how superior he thought he was—in his mind the punishment was justified by the offense, and how seriously he took the slights of his classmates can be seen as an index of how superior to them he thought he was. The greater the difference in relative worth between Harris and his schoolmates, the greater the injustice.

Perceived relative status plays a role in all punishments. Among two people of equal status, such factors as any uncertainty regarding guilt, mitigating circumstances surrounding the offense, and concern for making the punishment equal to the crime will enter into any consideration of just deserts. But the degree to which these factors are ignored can be used as an index for the size of the power differential between the two individuals—or at least to the perceived power differential. Someone who feels infinitely superior will be willing to dish out infinite punishment. Absent a truly horrendous crime, revenge is a narcissistic undertaking.

Also read

SYMPATHIZING WITH PSYCHOS: WHY WE WANT TO SEE ALEX ESCAPE HIS FATE AS A CLOCKWORK ORANGE

And:

THE MENTAL ILLNESS ZODIAC: WHY THE DSM 5 WON'T BE ANYTHING BUT MORE PSEUDOSCIENCE

Absurdities and Atrocities in Literary Criticism

Poststructuralists believe that everything we see is determined by language, which encapsulates all of culture, so our perceptions are hopelessly distorted. What can be done then to arrive at the truth? Well, nothing—all truth is constructed. All that effort scientists put into actually testing their ideas is a waste of time. They’re only going to “discover” what they already know.

All literary theories (except formalism) share one common attraction—they speak to the universal fantasy of being able to know more about someone than that person knows about him- or herself. If you happen to be a feminist critic for instance, then you will examine some author’s work and divine his or her attitude toward women. Because feminist theory insists that all or nearly all texts exemplify patriarchy if they’re not enacting some sort of resistance to it, the author in question will invariably be exposed as either a sexist or a feminist, regardless of whether or not that author intended to make any comment about gender. The author may complain of unfair treatment; indeed, there really is no clearer instance of unchecked confirmation bias. The important point, though, is that the writer of the text supposedly knows little or nothing about how the work functions in the wider culture, what really inspired it at an unconscious level, and what readers will do with it. Substitute bourgeois hegemony for patriarchy in the above formula and you have Marxist criticism. Deconstruction exposes hidden hierarchies. New Historicism teases out dominant and subversive discourses. And none of them flinches at objections from authors that their work has been completely misunderstood.

This has led to a sad, self-righteous state of affairs in English departments. The first wrong turn was taken by Freud when he introduced the world to the unconscious and subsequently failed to come up with a method that could bring its contents to light with any reliability whatsoever. It’s hard to imagine how he could’ve been more wrong about the contents of the human mind. As Voltaire said, “He who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities.” No sooner did Freud start writing about the unconscious than he began arguing that men want to kill their fathers and have sex with their mothers. Freud and his followers were fabulists who paid lip service to the principles of scientific epistemology even as they flouted them. But then came the poststructuralists to muddy the waters even more. When Derrida assured everyone that meaning derived from the play of signifiers, which actually meant meaning is impossible, and that referents—to the uninitiated, referents mean the real world—must be dismissed as having any part to play, he was sounding the death knell for any possibility of a viable epistemology. And if truth is completely inaccessible, what’s the point of even trying to use sound methods? Anything goes.

Since critics like to credit themselves with having good political intentions like advocating for women and minorities, they are quite adept at justifying their relaxing of the standards of truth. But just as Voltaire warned, once those standards are relaxed, critics promptly turn around and begin making accusations of sexism and classism and racism. And, since the accusations aren’t based on any reasonable standard of evidence, the accused have no recourse to counterevidence. They have no way of defending themselves. Presumably, their defense would be just another text the critics could read still more evidence into of whatever crime they’re primed to find.

The irony here is that the scientific method was first proposed, at least in part, as a remedy for confirmation bias, as can be seen in this quote from Francis Bacon’s 1620 treatise Novum Organon:

The human understanding is no dry light, but receives infusion from the will and affections; whence proceed sciences which may be called “sciences as one would.” For what a man had rather were true he more readily believes. Therefore he rejects difficult things from impatience of research; sober things, because they narrow hope; the deeper things of nature, from superstition; the light of experience, from arrogance and pride; things commonly believed, out of deference to the opinion of the vulgar. Numberless in short are the ways, and sometimes imperceptible, in which the affections color and infect the understanding.

Poststructuralists believe that everything we see is determined by language, which encapsulates all of culture, so our perceptions are hopelessly distorted. What can be done then to arrive at the truth? Well, nothing—all truth is constructed. All that effort scientists put into actually testing their ideas is a waste of time. They’re only going to “discover” what they already know.

But wait: if poststructuralism posits that discovery is impossible, how do its adherents account for airplanes and nuclear power? Just random historical fluctuations, I suppose.

The upshot is that, having declared confirmation bias inescapable, critics embraced it as their chief method. You have to accept their relaxed standard of truth to accept their reasoning about why we should do away with all standards of truth. And you just have to hope like hell they never randomly decide to set their sights on you or your work. We’re lucky as hell the legal system doesn’t work like this. And we can thank those white boys of the enlightenment for that.

Also read:

CAN’T WIN FOR LOSING: WHY THERE ARE SO MANY LOSERS IN LITERATURE AND WHY IT HAS TO CHANGE

WHY SHAKESPEARE NAUSEATED DARWIN: A REVIEW OF KEITH OATLEY'S "SUCH STUFF AS DREAMS"

SABBATH SAYS: PHILIP ROTH AND THE DILEMMAS OF IDEOLOGICAL CASTRATION

Poststructuralism: Banal When It's Not Busy Being Absurd

The dominant epistemology in the humanities, and increasingly the social sciences, is postmodernism, also known as poststructuralism—though pedants will object to the labels. It’s the idea that words have shaky connections to the realities they’re supposed to represent, and they’re shot through with ideological assumptions serving to perpetuate the current hegemonies in society. As a theory of language and cognition, it runs counter to nearly all the evidence that’s been gathered over the past century.

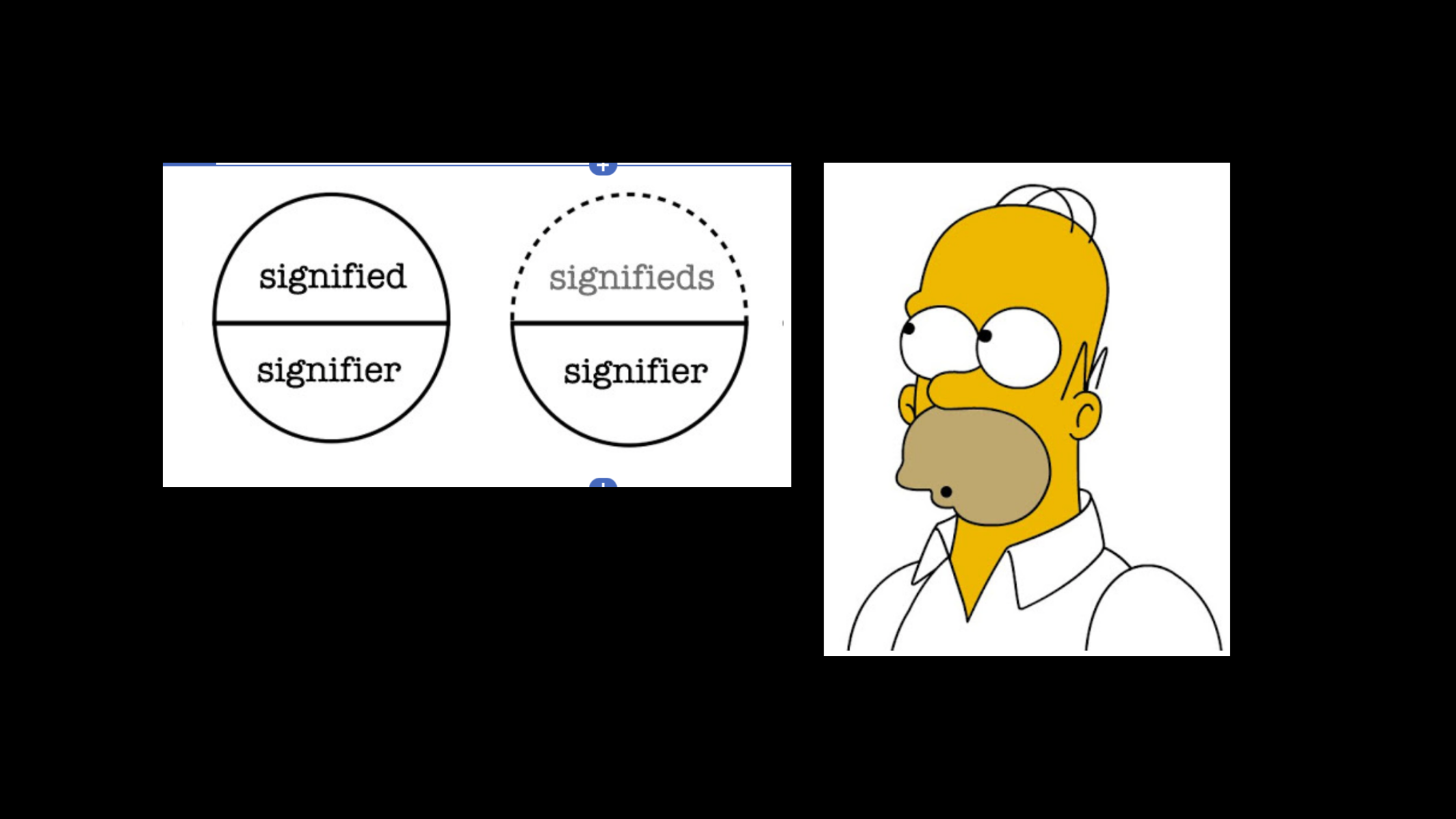

Reading the chapter in one of my textbooks on Poststructualism, I keep wondering why this paradigm has taken such a strong hold of scholars' minds in the humanities. In a lot of ways, the theories that fall under its aegis are really simple--overly simple in fact. The structuralism that has since been posted was the linguistic theory of Ferdinand de Saussure, who held that words derive their meanings from their relations to other, similar words. Bat means bat because it doesn't mean cat. Simple enough, but Saussure had to gussy up his theory by creating a more general category than "words," which he called signs. And, instead of talking about words and their meanings, he asserts that every sign is made up of a signifier (word) and a signified (concept or meaning).

What we don't see much of in Saussure's formulation of language is its relation to objects, actions, and experiences. These he labeled referents, and he doesn't think they play much of a role. And this is why structuralism is radical. The common-sense theory of language is that a word's meaning derives from its correspondence to the object it labels. Saussure flipped this understanding on its head, positing a top-down view of language. What neither Saussure nor any of his acolytes seemed to notice is that structuralism can only be an incomplete description of where meaning comes from because, well, it doesn't explain where meaning comes from--unless all the concepts, the signifieds are built into our brains. (Innate!)

Saussure's top-down theory of language has been, unbeknownst to scholars in the humanities, thoroughly discredited by research in developmental psychology going back to Jean Piaget that shows children's language acquisition begins very concretely and only later in life enables them to deal in abstractions. According to our best evidence, the common-sense, bottom-up theory of language is correct. But along came Jacques Derrida to put the post to structuralism--and make it even more absurd. Derrida realized that if words' meanings come from their relation to similar words then discerning any meaning at all from any given word is an endlessly complicated endeavor. Bat calls to mind not just cat, but also mat, and cad, and cot, ad infinitum. Now, it seems to me that this is a pretty effective refutation of Saussure's theory. But Derrida didn't scrap the faulty premise, but instead drew an amazing conclusion from it: that meaning is impossible.

Now, to round out the paradigm, you have to import some Marxism. Logically speaking, such an importation is completely unjustified; in fact, it contradicts the indeterminacy of meaning, making poststructuralism fundamentally unsound. But poststructuralists believe all ideas are incoherent, so this doesn't bother them. The Marxist element is the idea that there is always a more powerful group who's foisting their ideology on the less powerful. Derrida spoke of binaries like man and woman--a man is a man because he's not a woman--and black and white--blacks are black because they're not white. We have to ignore the obvious objection that some things can be defined according their own qualities without reference to something else. Derrida's argument is that in creating these binaries to structure our lives we always privilege one side over the other (men and whites of course--even though both Saussure and Derrida were both). So literary critics inspired by Derrida "deconstruct" texts to expose the privileging they take for granted and perpetuate. This gives wonks the gratifying sense of being engaged in social activism.

Is the fact that these ideas are esoteric what makes them so appealing to humanities scholars, the conviction that they have this understanding that supposedly discredits what the hoi polloi, or even what scientists and historians and writers of actual literature know? Really poststructuralism is nonsense on stilts riding a unicycle. It's banal in that it takes confirmation bias as a starting point, but it's absurd in that it insists this makes knowledge impossible. The linguist founders were armchair obscurantists whose theories have been disproved. But because of all the obscurantism learning the banalities and catching out the absurdities takes a lot of patient reading. So is the effort invested in learning the ideas a factor in making them hard to discount outright? After all, that would mean a lot of wasted effort.

Also read: