READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

The Feminist Sociobiologist: An Appreciation of Sarah Blaffer Hrdy Disguised as a Review of “Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding”

Sarah Blaffer Hrdy’s book “Mother Nature” was one of the first things I ever read about evolutionary psychology. With her new book, “Mothers and Others,” Hrdy lays out a theory for why humans are so cooperative compared to their ape cousins. Once again, she’s managed to pen a work that will stand the test of time, rewarding multiple readings well into the future.

One way to think of the job of anthropologists studying human evolution is to divide it into two basic components: the first is to arrive at a comprehensive and precise catalogue of the features and behaviors that make humans different from the species most closely related to us, and the second is to arrange all these differences in order of their emergence in our ancestral line. Knowing what came first is essential—though not sufficient—to the task of distinguishing between causes and effects. For instance, humans have brains that are significantly larger than those of any other primate, and we use these brains to fashion tools that are far more elaborate than the stones, sticks, leaves, and sponges used by other apes. Humans are also the only living ape that routinely walks upright on two legs. Since most of us probably give pride of place in the hierarchy of our species’ idiosyncrasies to our intelligence, we can sympathize with early Darwinian thinkers who felt sure brain expansion must have been what started our ancestors down their unique trajectory, making possible the development of increasingly complex tools, which in turn made having our hands liberated from locomotion duty ever more advantageous.

This hypothetical sequence, however, was dashed rather dramatically with the discovery in 1974 of Lucy, the 3.2 million-year-old skeleton of an Australopithecus Afarensis, in Ethiopia. Lucy resembles a chimpanzee in most respects, including cranial capacity, except that her bones have all the hallmarks of a creature with a bipedal gait. Anthropologists like to joke that Lucy proved butts were more important to our evolution than brains. But, though intelligence wasn’t the first of our distinctive traits to evolve, most scientists still believe it was the deciding factor behind our current dominance. At least for now, humans go into the jungle and build zoos and research facilities to study apes, not the other way around. Other apes certainly can’t compete with humans in terms of sheer numbers. Still, intelligence is a catch-all term. We must ask what exactly it is that our bigger brains can do better than those of our phylogenetic cousins.

A couple decades ago, that key capacity was thought to be language, which makes symbolic thought possible. Or is it symbolic thought that makes language possible? Either way, though a handful of ape prodigies have amassed some high vocabulary scores in labs where they’ve been taught to use pictographs or sign language, human three-year-olds accomplish similar feats as a routine part of their development. As primatologist and sociobiologist (one of the few who unabashedly uses that term for her field) Sarah Blaffer Hrdy explains in her 2009 book Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding, human language relies on abilities and interests aside from a mere reporting on the state of the outside world, beyond simply matching objects or actions with symbolic labels. Honeybees signal the location of food with their dances, vervet monkeys have distinct signals for attacks by flying versus ground-approaching predators, and the list goes on. Where humans excel when it comes to language is not just in the realm of versatility, but also in our desire to bond through these communicative efforts. Hrdy writes,

The open-ended qualities of language go beyond signaling. The impetus for language has to do with wanting to “tell” someone else what is on our minds and learn what is on theirs. The desire to psychologically connect with others had to evolve before language. (38)

The question Hrdy attempts to answer in Mothers and Others—the difference between humans and other apes she wants to place within a theoretical sequence of evolutionary developments—is how we evolved to be so docile, tolerant, and nice as to be able to cram ourselves by the dozens into tight spaces like airplanes without conflict. “I cannot help wondering,” she recalls having thought in a plane preparing for flight,

what would happen if my fellow human passengers suddenly morphed into another species of ape. What if I were traveling with a planeload of chimpanzees? Any of us would be lucky to disembark with all ten fingers and toes still attached, with the baby still breathing and unmaimed. Bloody earlobes and other appendages would litter the aisles. Compressing so many highly impulsive strangers into a tight space would be a recipe for mayhem. (3)

Over the past decade, the human capacity for cooperation, and even for altruism, has been at the center of evolutionary theorizing. Some clever experiments in the field of economic game theory have revealed several scenarios in which humans can be counted on to act against their own interest. What survival and reproductive advantages could possibly accrue to creatures given to acting for the benefit of others?

When it comes to economic exchanges, of course, human thinking isn’t tied to the here-and-now the way the thinking of other animals tends to be. To explain why humans might, say, forgo a small payment in exchange for the opportunity to punish a trading partner for withholding a larger, fairer payment, many behavioral scientists point out that humans seldom think in terms of one-off deals. Any human living in a society of other humans needs to protect his or her reputation for not being someone who abides cheating. Experimental settings are well and good, but throughout human evolutionary history individuals could never have been sure they wouldn’t encounter exchange partners a second or third time in the future. It so happens that one of the dominant theories to explain ape intelligence relies on the need for individuals within somewhat stable societies to track who owes whom favors, who is subordinate to whom, and who can successfully deceive whom. This “Machiavellian intelligence” hypothesis explains the cleverness of humans and other apes as the outcome of countless generations vying for status and reproductive opportunities in intensely competitive social groups.

One of the difficulties in trying to account for the evolution of intelligence is that its advantages seem like such a no-brainer. Isn’t it always better to be smarter? But, as Hrdy points out, the Machiavellian intelligence hypothesis runs into a serious problem. Social competition may have been an important factor in making primates brainer than other mammals, but it can’t explain why humans are brainer than other apes. She writes,

We still have to explain why humans are so much better than chimpanzees at conceptualizing what others are thinking, why we are born innately eager to interpret their motives, feelings, and intentions as well as care about their affective states and moods—in short, why humans are so well equipped for mutual understanding. Chimpanzees, after all, are at least as socially competitive as humans are. (46)

To bolster this point, Hrdy cites research showing that infant chimps have some dazzling social abilities once thought to belong solely to humans. In 1977, developmental psychologist Andrew Meltzoff published his finding that newborn humans mirror the facial expressions of adults they engage with. It was thought that this tendency in humans relied on some neurological structures unique to our lineage which provided the raw material for the evolution of our incomparable social intelligence. But then in 1996 primatologist Masako Myowa replicated Meltzoff’s findings with infant chimps. This and other research suggests that other apes have probably had much the same raw material for natural selection to act on. Yet, whereas the imitative and empathic skills flourish in maturing humans, they seem to atrophy in apes. Hrdy explains,

Even though other primates are turning out to be far better at reading intentions than primatologists initially realized, early flickerings of empathic interest—what might even be termed tentative quests for intersubjective engagement—fade away instead of developing and intensifying as they do in human children. (58)

So the question of what happened in human evolution to make us so different remains.

*****

Sarah Blaffer Hrdy exemplifies a rare, possibly unique, blend of scientific rigor and humanistic sensitivity—the vision of a great scientist and the fine observation of a novelist (or the vision of a great novelist and fine observation of a scientist). Reading her 1999 book, Mother Nature: A History of Mothers, Infants, and Natural Selection, was a watershed experience for me. In going beyond the realm of the literate into that of the literary while hewing closely to strict epistemic principle, she may surpass the accomplishments of even such great figures as Richard Dawkins and Stephen Jay Gould. In fact, since Mother Nature was one of the books through which I was introduced to sociobiology—more commonly known today as evolutionary psychology—I was a bit baffled at first by much of the criticism leveled against the field by Gould and others who claimed it was founded on overly simplistic premises and often produced theories that were politically reactionary.

The theme to which Hrdy continually returns is the too-frequently overlooked role of women and their struggles in those hypothetical evolutionary sequences anthropologists string together. For inspiration in her battle against facile biological theories whose sole purpose is to provide a cheap rationale for the political status quo, she turned, not to a scientist, but a novelist. The man single-most responsible for the misapplication of Darwin’s theory of natural selection to the justification of human societal hierarchies was the philosopher Herbert Spencer, in whose eyes women were no more than what Hrdy characterizes as “Breeding Machines.” Spencer and his fellow evolutionists in the Victorian age, she explains in Mother Nature,

took for granted that being female forestalled women from evolving “the power of abstract reasoning and that most abstract of emotions, the sentiment of justice.” Predestined to be mothers, women were born to be passive and noncompetitive, intuitive rather than logical. Misinterpretations of the evidence regarding women’s intelligence were cleared up early in the twentieth century. More basic difficulties having to do with this overly narrow definition of female nature were incorporated into Darwinism proper and linger to the present day. (17)

Many women over the generations have been unable to envision a remedy for this bias in biology. Hrdy describes the reaction of a literary giant whose lead many have followed.

For Virginia Woolf, the biases were unforgivable. She rejected science outright. “Science, it would seem, in not sexless; she is a man, a father, and infected too,” Woolf warned back in 1938. Her diagnosis was accepted and passed on from woman to woman. It is still taught today in university courses. Such charges reinforce the alienation many women, especially feminists, feel toward evolutionary theory and fields like sociobiology. (xvii)

But another literary luminary much closer to the advent of evolutionary thinking had a more constructive, and combative, response to short-sighted male biologists. And it is to her that Hrdy looks for inspiration. “I fall in Eliot’s camp,” she writes, “aware of the many sources of bias, but nevertheless impressed by the strength of science as a way of knowing” (xviii). She explains that George Eliot,

whose real name was Mary Ann Evans, recognized that her own experiences, frustrations, and desires did not fit within the narrow stereotypes scientists then prescribed for her sex. “I need not crush myself… within a mould of theory called Nature!” she wrote. Eliot’s primary interest was always human nature as it could be revealed through rational study. Thus she was already reading an advance copy of On the Origin of Species on November 24, 1859, the day Darwin’s book was published. For her, “Science has no sex… the mere knowing and reasoning faculties, if they act correctly, must go through the same process and arrive at the same result.” (xvii)

Eliot’s distaste for Spencer’s idea that women’s bodies were designed to divert resources away from the brain to the womb was as personal as it was intellectual. She had in fact met and quickly fallen in love with Spencer in 1851. She went on to send him a proposal which he rejected on eugenic grounds: “…as far as posterity is concerned,” Hrdy quotes, “a cultivated intelligence based upon a bad physique is of little worth, seeing that its descendants will die out in a generation or two.” Eliot’s retort came in the form of a literary caricature—though Spencer already seems a bit like his own caricature. Hrdy writes,

In her first major novel, Adam Bede (read by Darwin as he relaxed after the exertions of preparing Origin for publication), Eliot put Spencer’s views concerning the diversion of somatic energy into reproduction in the mouth of a pedantic and blatantly misogynist old schoolmaster, Mr. Bartle: “That’s the way with these women—they’ve got no head-pieces to nourish, and so their food all runs either to fat or brats.” (17)

A mother of three and an Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Davis, Hrdy is eloquent on the need for intelligence—and lots of familial and societal support—if one is to balance duties and ambitions like her own. Her first contribution to ethology came when she realized that the infanticide among hanuman langurs, which she’d gone to Mount Abu in Rajasthan, India to study at age 26 for her doctoral thesis, had nothing to do with overpopulation, as many suspected. Instead, the pattern she observed was that whenever an outside male deposed a group’s main breeder he immediately began exterminating all of the prior male’s offspring to induce the females to ovulate and give birth again—this time to the new male’s offspring. This was the selfish gene theory in action. But the females Hrdy was studying had an interesting response to this strategy.

In the early 1970s, it was still widely assumed by Darwinians that females were sexually passive and “coy.” Female langurs were anything but. When bands of roving males approached the troop, females would solicit them or actually leave their troop to go in search of them. On occasion, a female mated with invaders even though she was already pregnant and not ovulating (something else nonhuman primates were not supposed to do). Hence, I speculated that mothers were mating with outside males who might take over her troop one day. By casting wide the web of possible paternity, mothers could increase the prospects of future survival of offspring, since males almost never attack infants carried by females that, in the biblical sense of the word, they have “known.” Males use past relations with the mother as a cue to attack or tolerate her infant. (35)

Hrdy would go on to discover this was just one of myriad strategies primate females use to get their genes into future generations. The days of seeing females as passive vehicles while the males duke it out for evolutionary supremacy were now numbered.

I’ll never forget the Young-Goodman-Brown experience of reading the twelfth chapter of Mother Nature, titled “Unnatural Mothers,” and covering an impressive variety of evidence sources that simply devastates any notion of women as nurturing automatons, evolved for the sole purpose of serving as loving mothers. The verdict researchers arrive at whenever they take an honest look into the practices of women with newborns is that care is contingent. To give just one example, Hrdy cites the history of one of the earliest foundling homes in the world, the “Hospital of the Innocents” in Florence.

Founded in 1419, with assistance from the silk guilds, the Ospedale delgi Innocenti was completed in 1445. Ninety foundlings were left there the first year. By 1539 (a famine year), 961 babies were left. Eventually five thousand infants a year poured in from all corners of Tuscany. (299)

What this means is that a troubling number of new mothers were realizing they couldn't care for their infants. Unfortunately, newborns without direct parental care seldom fare well. “Of 15,000 babies left at the Innocenti between 1755 and 1773,” Hrdy reports, “two thirds died before reaching their first birthday” (299). And there were fifteen other foundling homes in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany at the time.

The chapter amounts to a worldwide tour of infant abandonment, exposure, or killing. (I remember having a nightmare after reading it about being off-balance and unable to set a foot down without stepping on a dead baby.) Researchers studying sudden infant death syndrome in London set up hidden cameras to monitor mothers interacting with babies but ended up videotaping them trying to smother them. Cases like this have made it necessary for psychiatrists to warn doctors studying the phenomenon “that some undeterminable portion of SIDS cases might be infanticides” (292). Why do so many mothers abandon or kill their babies? Turning to the ethnographic data, Hrdy explains,

Unusually detailed information was available for some dozen societies. At a gross level, the answer was obvious. Mothers kill their own infants where other forms of birth control are unavailable. Mothers were unwilling to commit themselves and had no way to delegate care of the unwanted infant to others—kin, strangers, or institutions. History and ecological constraints interact in complex ways to produce different solutions to unwanted births. (296)

Many scholars see the contingent nature of maternal care as evidence that motherhood is nothing but a social construct. Consistent with the blank-slate view of human nature, this theory holds that every aspect of child-rearing, whether pertaining to the roles of mothers or fathers, is determined solely by culture and therefore must be learned. Others, who simply can’t let go of the idea of women as virtuous vessels, suggest that these women, as numerous as they are, must all be deranged.

Hrdy demolishes both the purely social constructivist view and the suggestion of pathology. And her account of the factors that lead women to infanticide goes to the heart of her arguments about the centrality of female intelligence in the history of human evolution. Citing the pioneering work of evolutionary psychologists Martin Daly and MargoWilson, Hrdy writes,

How a mother, particularly a very young mother, treats one infant turns out to be a poor predictor of how she might treat another one born when she is older, or faced with improved circumstances. Even with culture held constant, observing modern Western women all inculcated with more or less the same post-Enlightenment values, maternal age turned out to be a better predictor of how effective a mother would be than specific personality traits or attitudes. Older women describe motherhood as more meaningful, are more likely to sacrifice themselves on behalf of a needy child, and mourn lost pregnancies more than do younger women. (314)

The takeaway is that a woman, to reproduce successfully, must assess her circumstances, including the level of support she can count on from kin, dads, and society. If she lacks the resources or the support necessary to raise the child, she may have to make a hard decision. But making that decision in the present unfavorable circumstances in no way precludes her from making the most of future opportunities to give birth to other children and raise them to reproductive age.

Hrdy goes on to describe an experimental intervention that took place in a hospital located across the street from a foundling home in 17th century France. The Hospice des Enfants Assistes cared for indigent women and assisted them during childbirth. It was the only place where poor women could legally abandon their babies. What the French reformers did was tell a subset of the new mothers that they had to stay with their newborns for eight days after birth.

Under this “experimental” regimen, the proportion of destitute mothers who subsequently abandoned their babies dropped from 24 to 10 percent. Neither cultural concepts about babies nor their economic circumstances had changed. What changed was the degree to which they had become attached to their breast-feeding infants. It was as though their decision to abandon their babies and their attachment to their babies operated as two different systems. (315)

Following the originator of attachment theory, John Bowlby, who set out to integrate psychiatry and developmental psychology into an evolutionary framework, Hrdy points out that the emotions underlying the bond between mothers and infants (and fathers and infants too) are as universal as they are consequential. Indeed, the mothers who are forced to abandon their infants have to be savvy enough to realize they have to do so before these emotions are engaged or they will be unable to go through with the deed.

Female strategy plays a crucial role in reproductive outcomes in several domains beyond the choice of whether or not to care for infants. Women must form bonds with other women for support, procure the protection of men (usually from other men), and lay the groundwork for their children’s own future reproductive success. And that’s just what women have to do before choosing a mate—a task that involves striking a balance between good genes and a high level of devotion—getting pregnant, and bringing the baby to term. The demographic transition that occurs when an agrarian society becomes increasingly industrialized is characterized at first by huge population increases as infant mortality drops but then levels off as women gain more control over their life trajectories. Here again, the choices women tend to make are at odds with Victorian (and modern evangelical) conceptions of their natural proclivities. Hrdy writes,

Since, formerly, status and well-being tended to be correlated with reproductive success, it is not surprising that mothers, especially those in higher social ranks, put the basics first. When confronted with a choice between striving for status and striving for children, mothers gave priority to status and “cultural success” ahead of a desire for many children. (366)

And then of course come all the important tasks and decisions associated with actually raising any children the women eventually do give birth to. One of the basic skill sets women have to master to be successful mothers is making and maintaining friendships; they must be socially savvy because more than with any other ape the support of helpers, what Hrdy calls allomothers, will determine the fate of their offspring.

*****

Mother Nature is a massive work—541pages before the endnotes—exploring motherhood through the lens of sociobiology and attachment theory. Mothers and Others is leaner, coming in at just under 300 pages, because its focus is narrower. Hrdy feels that in attempting to account for humans’ prosocial impulses over the past decade, the role of women and motherhood has once again been scanted. She points to the prevalence of theories focusing on competition between groups, with the edge going to those made up of the most cooperative and cohesive members. Such theories once again give the leading role to males and their conflicts, leaving half the species out of the story—unless that other half’s only role is to tend to the children and forage for food while the “band of brothers” is out heroically securing borders.

Hrdy doesn’t weigh in directly on the growing controversy over whether group selection has operated as a significant force in human evolution. The problem she sees with intertribal warfare as an explanation for human generosity and empathy is that the timing isn’t right. What Hrdy is after are the selection pressures that led to the evolution of what she calls “emotionally modern humans,” the “people preadapted to get along with one another even when crowded together on an airplane” (66). And she argues that humans must have been emotionally modern before they could have further evolved to be cognitively modern. “Brains require care more than caring requires brains” (176). Her point is that bonds of mutual interest and concern came before language and the capacity for runaway inventiveness. Humans, Hrdy maintains, would have had to begin forming these bonds long before the effects of warfare were felt.

Apart from periodic increases in unusually rich locales, most Pleistocene humans lived at low population densities. The emergence of human mind reading and gift-giving almost certainly preceded the geographic spread of a species whose numbers did not begin to really expand until the past 70,000 years. With increasing population density (made possible, I would argue, because they were already good at cooperating), growing pressure on resources, and social stratification, there is little doubt that groups with greater internal cohesion would prevail over less cooperative groups. But what was the initial payoff? How could hypersocial apes evolve in the first place? (29)

In other words, what was it that took inborn capacities like mirroring an adult’s facial expressions, present in both human and chimp infants, and through generations of natural selection developed them into the intersubjective tendencies displayed by humans today?

Like so many other anthropologists before her, Hrdy begins her attempt to answer this question by pointing to a trait present in humans but absent in our fellow apes. “Under natural conditions,” she writes, “an orangutan, chimpanzee, or gorilla baby nurses for four to seven years and at the outset is inseparable from his mother, remaining in intimate front-to-front contact 100 percent of the day and night” (68). But humans allow others to participate in the care of their babies almost immediately after giving birth to them. Who besides Sarah Blaffer Hrdy would have noticed this difference, or given it more than a passing thought? (Actually, there are quite a few candidates among anthropologists—Kristen Hawkes for instance.) Ape mothers remain in constant contact with their infants, whereas human mothers often hand over their babies to other women to hold as soon as they emerge from the womb. The difference goes far beyond physical contact. Humans are what Hrdy calls “cooperative breeders,” meaning a child will in effect have several parents aside from the primary one. Help from alloparents opens the way for an increasingly lengthy development, which is important because the more complex the trait—and human social intelligence is about as complex as they come—the longer it takes to develop in maturing individuals. Hrdy writes,

One widely accepted tenet of life history theory is that, across species, those with bigger babies relative to the mother’s body size will also tend to exhibit longer intervals between births because the more babies cost the mother to produce, the longer she will need to recoup before reproducing again. Yet humans—like marmosets—provide a paradoxical exception to this rule. Humans, who of all the apes produce the largest, slowest-maturing, and most costly babies, also breed the fastest. (101)

Those marmosets turn out to be central to Hrdy’s argument because, along with their cousins in the family Callitrichidae, the tamarins, they make up almost the totality of the primate species whom she classifies as “full-fledged cooperative breeders” (92). This and other similarities between humans and marmosets and tamarins have long been overlooked because anthropologists have understandably been focused on the great apes, as well as other common research subjects like baboons and macaques.

Golden Lion Tamarins, by Sarah Landry

Callitrichidae, it so happens, engage in some uncannily human-like behaviors. Plenty of primate babies wail and shriek when they’re in distress, but infants who are frequently not in direct contact with their mothers would have to find a way to engage with them, as well as other potential caregivers, even when they aren’t in any trouble. “The repetitive, rhythmical vocalizations known as babbling,” Hrdy points out, “provided a particularly elaborate way to accomplish this” (122). But humans aren’t the only primates that babble “if by babble we mean repetitive strings of adultlike vocalizations uttered without vocal referents”; marmosets and tamarins do it too. Some of the other human-like patterns aren’t as cute though. Hrdy writes,

Shared care and provisioning clearly enhances maternal reproductive success, but there is also a dark side to such dependence. Not only are dominant females (especially pregnant ones) highly infanticidal, eliminating babies produced by competing breeders, but tamarin mothers short on help may abandon their own young, bailing out at birth by failing to pick up neonates when they fall to the ground or forcing clinging newborns off their bodies, sometimes even chewing on their hands or feet. (99)

It seems that the more cooperative infant care tends to be for a given species the more conditional it is—the more likely it will be refused when the necessary support of others can’t be counted on.

Hrdy’s cooperative breeding hypothesis is an outgrowth of George Williams and Kristen Hawkes’s so-called “Grandmother Hypothesis.” For Hawkes, the important difference between humans and apes is that human females go on living for decades after menopause, whereas very few female apes—or any other mammals for that matter—live past their reproductive years. Hawkes hypothesized that the help of grandmothers made it possible for ever longer periods of dependent development for children, which in turn made it possible for the incomparable social intelligence of humans to evolve. Until recently, though, this theory had been unconvincing to anthropologists because a renowned compendium of data compiled by George Peter Murdock in his Ethnographic Atlas revealed that there was a strong trend toward patrilocal residence patterns in all the societies that had been studied. Since grandmothers are thought to be much more likely to help care for their daughters’ children than their sons’—owing to paternity uncertainty—the fact that most humans raise their children far from maternal grandmothers made any evolutionary role for them unlikely.

But then in 2004 anthropologist Helen Alvarez reexamined Murdock’s analysis of residence patterns and concluded that pronouncements about widespread patrilocality were based on a great deal of guesswork. After eliminating societies for which too little evidence existed to determine the nature of their residence practices, Alvarez calculated that the majority of the remaining societies were bilocal, which means couples move back and forth between the mother’s and the father’s groups. Citing “The Alvarez Corrective” and other evidence, Hrdy concludes,

Instead of some highly conserved tendency, the cross-cultural prevalence of patrilocal residence patterns looks less like an evolved human universal than a more recent adaptation to post-Pleistocene conditions, as hunters moved into northern climes where women could no longer gather wild plants year-round or as groups settled into circumscribed areas. (246)

But Hrdy extends the cast of alloparents to include a mother’s preadult daughters, as well as fathers and their extended families, although the male contribution is highly variable across cultures (and variable too of course among individual men).

With the observation that human infants rely on multiple caregivers throughout development, Hrdy suggests the mystery of why selection favored the retention and elaboration of mind reading skills in humans but not in other apes can be solved by considering the life-and-death stakes for human babies trying to understand the intentions of mothers and others. She writes,

Babies passed around in this way would need to exercise a different skill set in order to monitor their mothers’ whereabouts. As part of the normal activity of maintaining contact both with their mothers and with sympathetic alloparents, they would find themselves looking for faces, staring at them, and trying to read what they reveal. (121)

Mothers, of course, would also have to be able to read the intentions of others whom they might consider handing their babies over to. So the selection pressure occurs on both sides of the generational divide. And now that she’s proposed her candidate for the single most pivotal transition in human evolution Hrdy’s next task is to place it in a sequence of other important evolutionary developments.

Without a doubt, highly complex coevolutionary processes were involved in the evolution of extended lifespans, prolonged childhoods, and bigger brains. What I want to stress here, however, is that cooperative breeding was the pre-existing condition that permitted the evolution of these traits in the hominin line. Creatures may not need big brains to evolve cooperative breeding, but hominins needed shared care and provisioning to evolve big brains. Cooperative breeding had to come first. (277)

*****

Flipping through Mother Nature, a book I first read over ten years ago, I can feel some of the excitement I must have experienced as a young student of behavioral science, having graduated from the pseudoscience of Freud and Jung to the more disciplined—and in its way far more compelling—efforts of John Bowlby, on a path, I was sure, to becoming a novelist, and now setting off into this newly emerging field with the help of a great scientist who saw the value of incorporating literature and art into her arguments, not merely as incidental illustrations retrofitted to recently proposed principles, but as sources of data in their own right, and even as inspiration potentially lighting the way to future discovery. To perceive, to comprehend, we must first imagine. And stretching the mind to dimensions never before imagined is what art is all about.

Yet there is an inescapable drawback to massive books like Mother Nature—for writers and readers alike—which is that any effort to grasp and convey such a massive array of findings and theories comes with the risk of casual distortion since the minutiae mastered by the experts in any subdiscipline will almost inevitably be heeded insufficiently in the attempt to conscript what appear to be basic points in the service of a broader perspective. Even more discouraging is the assurance that any intricate tapestry woven of myriad empirical threads will inevitably be unraveled by ongoing research. Your tapestry is really a snapshot taken from a distance of a field in flux, and no sooner does the shutter close than the beast continues along the path of its stubbornly unpredictable evolution.

When Mothers and Others was published just four years ago in 2009, for instance, reasoning based on the theory of kin selection led most anthropologists to assume, as Hrdy states, that “forager communities are composed of flexible assemblages of close and more distant blood relations and kin by marriage” (132).

This assumption seems to have been central to the thinking that led to the principal theory she lays out in the book, as she explains that “in foraging contexts the majority of children alloparents provision are likely to be cousins, nephews, and nieces rather than unrelated children” (158). But as theories evolve old assumptions come under new scrutiny, and in an article published in the journal Science in March of 2011 anthropologist Kim Hill and his colleagues report that after analyzing the residence and relationship patterns of 32 modern foraging societies their conclusion is that “most individuals in residential groups are genetically unrelated” (1286). In science, two years can make a big difference. This same study does, however, bolster a different pillar of Hrdy’s argument by demonstrating that men relocate to their wives’ groups as often as women relocate to their husbands’, lending further support to Alvarez’s corrective of Murdock’s data.

Even if every last piece of evidence she marshals in her case for how pivotal the transition to cooperative breeding was in the evolution of mutual understanding in humans is overturned, Hrdy’s painstaking efforts to develop her theory and lay it out so comprehensively, so compellingly, and so artfully, will not have been wasted. Darwin once wrote that “all observation must be for or against some view to be of any service,” but many scientists, trained as they are to keep their eyes on the data and to avoid the temptation of building grand edifices on foundations of inference and speculation, look askance at colleagues who dare to comment publically on fields outside their specialties, especially in cases like Jared Diamond’s where their efforts end up winning them Pulitzers and guaranteed audiences for their future works.

But what use are legions of researchers with specialized knowledge hermetically partitioned by narrowly focused journals and conferences of experts with homogenous interests? Science is contentious by nature, so whenever a book gains notoriety with a nonscientific audience we can count on groaning from the author’s colleagues as they rush to assure us what we’ve read is a misrepresentation of their field. But stand-alone findings, no matter how numerous, no matter how central they are to researchers’ daily concerns, can’t compete with the grand holistic visions of the Diamonds, Hrdys, or Wilsons, imperfect and provisional as they must be, when it comes to inspiring the next generation of scientists. Nor can any number of correlation coefficients or regression analyses spark anything like the same sense of wonder that comes from even a glimmer of understanding about how a new discovery fits within, and possibly transforms, our conception of life and the universe in which it evolved. The trick, I think, is to read and ponder books like the ones Sarah Blaffer Hrdy writes as soon as they’re published—but to be prepared all the while, as soon as you’re finished reading them, to read and ponder the next one, and the one after that.

Also read:

And:

And:

NAPOLEON CHAGNON'S CRUCIBLE AND THE ONGOING EPIDEMIC OF MORALIZING HYSTERIA IN ACADEMIA

The People Who Evolved Our Genes for Us: Christopher Boehm on Moral Origins – Part 3 of A Crash Course in Multilevel Selection Theory

In “Moral Origins,” anthropologist Christopher Boehm lays out the mind-blowing theory that humans evolved to be cooperative in large part by developing mechanisms to keep powerful men’s selfish impulses in check. These mechanisms included, in rare instances, capital punishment. Once the free-rider problem was addressed, groups could function more as a unit than as a collection of individuals.

In a 1969 account of her time in Labrador studying the culture of the Montagnais-Naskapi people, anthropologist Eleanor Leacock describes how a man named Thomas, who was serving as her guide and informant, responded to two men they encountered while far from home on a hunting trip. The men, whom Thomas recognized but didn’t know very well, were on the brink of starvation. Even though it meant ending the hunting trip early and hence bringing back fewer furs to trade, Thomas gave the hungry men all the flour and lard he was carrying. Leacock figured that Thomas must have felt at least somewhat resentful for having to cut short his trip and that he was perhaps anticipating some return favor from the men in the future. But Thomas didn’t seem the least bit reluctant to help or frustrated by the setback. Leacock kept pressing him for an explanation until he got annoyed with her probing. She writes,

This was one of the very rare times Thomas lost patience with me, and he said with deep, if suppressed anger, “suppose now, not to give them flour, lard—just dead inside.” More revealing than the incident itself were the finality of his tone and the inference of my utter inhumanity in raising questions about his action. (Quoted in Boehm 219)

The phrase “just dead inside” expresses how deeply internalized the ethic of sympathetic giving is for people like Thomas who live in cultures more similar to those our earliest human ancestors created at the time, around 45,000 years ago, when they began leaving evidence of engaging in all the unique behaviors that are the hallmarks of our species. The Montagnais-Naskapi don’t qualify as an example of what anthropologist Christopher Boehm labels Late Pleistocene Appropriate, or LPA, cultures because they had been involved in fur trading with people from industrialized communities going back long before their culture was first studied by ethnographers. But Boehm includes Leacock’s description in his book Moral Origins: The Evolution of Virtue, Altruism, and Shame because he believes Thomas’s behavior is in fact typical of nomadic foragers and because, infelicitously for his research, standard ethnographies seldom cover encounters like the one Thomas had with those hungry acquaintances of his.

In our modern industrialized civilization, people donate blood, volunteer to fight in wars, sign over percentages of their income to churches, and pay to keep organizations like Doctors without Borders and Human Rights Watch in operation even though the people they help live in far-off countries most of us will never visit. One approach to explaining how this type of extra-familial generosity could have evolved is to suggest people who live in advanced societies like ours are, in an important sense, not in their natural habitat. Among evolutionary psychologists, it has long been assumed that in humans’ ancestral environments, most of the people individuals encountered would either be close kin who carried many genes in common, or at the very least members of a moderately stable group they could count on running into again, at which time they would be disposed to repay any favors. Once you take kin selection and reciprocal altruism into account, the consensus held, there was not much left to explain. Whatever small acts of kindness that weren’t directed toward kin or done with an expectation of repayment were, in such small groups, probably performed for the sake of impressing all the witnesses and thus improving the social status of the performer. As the biologist Michael Ghiselin once famously put it, “Scratch an altruist and watch a hypocrite bleed.” But this conception of what evolutionary psychologists call the Environment of Evolutionary Adaptedness, or EEA, never sat right with Boehm.

One problem with the standard selfish gene scenario that has just recently come to light is that modern hunter-gatherers, no matter where in the world they live, tend to form bands made up of high percentages of non-related or distantly related individuals. In an article published in Science in March of 2011, anthropologist Kim Hill and his colleagues report the findings of their analysis of thirty-two hunter-gatherer societies. The main conclusion of the study is that the members of most bands are not closely enough related for kin selection to sufficiently account for the high levels of cooperation ethnographers routinely observe. Assuming present-day forager societies are representative of the types of groups our Late Pleistocene ancestors lived in, we can rule out kin selection as a likely explanation for altruism of the sort displayed by Thomas or by modern philanthropists in complex civilizations. Boehm offers us a different scenario, one that relies on hypotheses derived from ethological studies of apes and archeological records of our human prehistory as much as on any abstract mathematical accounting of the supposed genetic payoffs of behaviors.

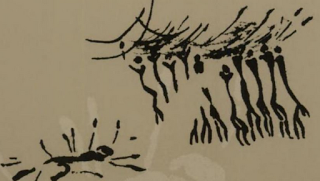

In three cave paintings discovered in Spain that probably date to the dawn of the Holocene epoch around 12,000 years ago, groups of men are depicted with what appear to be bows lifted above their heads in celebration while another man lay dead nearby with one arrow from each of them sticking out of his body. We can only speculate about what these images might have meant to the people who created them, but Boehm points out that all extant nomadic foraging peoples, no matter what part of the world they live in, are periodically forced to reenact dramas that resonate uncannily well with these scenes portrayed in ancient cave art. “Given enough time,” he writes, “any band society is likely to experience a problem with a homicide-prone unbalanced individual. And predictably band members will have to solve the problem by means of execution” (253). One of the more gruesome accounts of such an incident he cites comes from Richard Lee’s ethnography of !Kung Bushmen. After a man named /Twi had killed two men, Lee writes, “A number of people decided that he must be killed.” According to Lee’s informant, a man named =Toma (the symbols before the names represent clicks), the first attempt to kill /Twi was botched, allowing him to return to his hut, where a few people tried to help him. But he ended up becoming so enraged that he grabbed a spear and stabbed a woman in the face with it. When the woman’s husband came to her aid, /Twi shot him with a poisoned arrow, killing him and bringing his total body count to four. =Toma continues the story,

Now everyone took cover, and others shot at /Twi, and no one came to his aid because all those people had decided he had to die. But he still chased after some, firing arrows, but he didn’t hit any more…Then they all fired on him with poisoned arrows till he looked like a porcupine. Then he lay flat. All approached him, men and women, and stabbed his body with spears even after he was dead. (261-2)

The two most important elements of this episode for Boehm are the fact that the death sentence was arrived at through a partial group consensus which ended up being unanimous, and that it was carried out with weapons that had originally been developed for hunting. But this particular case of collectively enacted capital punishment was odd not just in how clumsy it was. Boehm writes,

In this one uniquely detailed description of what seems to begin as a delegated execution and eventually becomes a fully communal killing, things are so chaotic that it’s easy to understand why with hunter-gatherers the usual mode of execution is to efficiently delegate a kinsman to quickly kill the deviant by ambush. (261)

The prevailing wisdom among evolutionary psychologists has long been that any appearance of group-level adaptation, like the collective killing of a dangerous group member, must be an illusory outcome caused by selection at the level of individuals or families. As Steven Pinker explains, “If a person has innate traits that encourage him to contribute to the group’s welfare and as a result contribute to his own welfare, group selection is unnecessary; individual selection in the context of group living is adequate.” To demonstrate that some trait or behavior humans reliably engage in really is for the sake of the group as opposed to the individual engaging in it, there would have to be some conflict between the two motives—serving the group would have to entail incurring some kind of cost for the individual. Pinker explains,

It’s only when humans display traits that are disadvantageous to themselves while benefiting their group that group selection might have something to add. And this brings us to the familiar problem which led most evolutionary biologists to reject the idea of group selection in the 1960s. Except in the theoretically possible but empirically unlikely circumstance in which groups bud off new groups faster than their members have babies, any genetic tendency to risk life and limb that results in a net decrease in individual inclusive fitness will be relentlessly selected against. A new mutation with this effect would not come to predominate in the population, and even if it did, it would be driven out by any immigrant or mutant that favored itself at the expense of the group.

The ever-present potential for cooperative or altruistic group norms to be subverted by selfish individuals keen on exploitation is known in game theory as the free rider problem. To see how strong selfish individuals can lord over groups of their conspecifics we can look to the hierarchically organized bands great apes naturally form.

In groups of chimpanzees, for instance, an alpha male gets to eat his fill of the most nutritious food, even going so far at times as seizing meat from the subordinates who hunted it down. The alpha chimp also works to secure, as best he can, sole access to reproductively receptive females. For a hierarchical species like this, status is a winner-take-all competition, and so genes for dominance and cutthroat aggression proliferate. Subordinates tolerate being bullied because they know the more powerful alpha will probably kill them if they try to stand up for themselves. If instead of mounting some ill-fated resistance, however, they simply bide their time, they may eventually grow strong enough to more effectively challenge for the top position. Meanwhile, they can also try to sneak off with females to couple behind the alpha’s back. Boehm suggests that two competing motives keep hierarchies like this in place: one is a strong desire for dominance and the other is a penchant for fear-based submission. What this means is that subordinates only ever submit ambivalently. They even have a recognizable vocalization, which Boehm transcribes as the “waa,” that they use to signal their discontent. In his 1999 book Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior, Boehm explains,

When an alpha male begins to display and a subordinate goes screaming up a tree, we may interpret this as a submissive act of fear; but when that same subordinate begins to waa as the display continues, it is an open, hostile expression of insubordination. (167)

Since the distant ancestor humans shared in common with chimpanzees likely felt this same ambivalence toward alphas, Boehm theorizes that it served as a preadaptation for the type of treatment modern human bullies can count on in every society of nomadic foragers anthropologists have studied. “I believe,” he writes, “that a similar emotional and behavioral orientation underlies the human moral community’s labeling of domination behaviors as deviant” (167).

Boehm has found accounts of subordinate chimpanzees, bonobos, and even gorillas banding together with one or more partner to take on an excessively domineering alpha—though there was only one case in which this happened with gorillas and the animals in question lived in captivity. But humans are much better at this type of coalition building. Two of the most crucial developments in our own lineage that lead to the differences in social organization between ourselves and the other apes were likely to have been an increased capacity for coordinated hunting and the invention of weapons designed to kill big game. As Boehm explains,

Weapons made possible not only killing at a distance, but far more effective threat behavior; brandishing a projectile could turn into an instant lethal attack with relatively little immediate risk to the attacker. (175)

Deadly weapons fundamentally altered the dynamic between lone would-be bullies and those they might try to dominate. As Boehm points out, “after weapons arrived, the camp bully became far more vulnerable” (177). With the advent of greater coalition-building skills and the invention of tools for efficient killing, the opportunities for an individual to achieve alpha status quickly vanished.

It’s dangerous to assume that any one group of modern people provides the key to understanding our Pleistocene ancestors, but when every group living with similar types of technology and subsistence methods as those ancestors follows a similar pattern it’s much more suggestive. “A distinctively egalitarian political style,” Boehm writes, “is highly predictable wherever people live in small, locally autonomous social and economic groups” (35-6). This egalitarianism must be vigilantly guarded because “A potential bully always seems to be waiting in the wings” (68). Boehm explains what he believes is the underlying motivation,

Even though individuals may be attracted personally to a dominant role, they make a common pact which says that each main political actor will give up his modest chances of becoming alpha in order to be certain that no one will ever be alpha over him. (105)

The methods used to prevent powerful or influential individuals from acquiring too much control include such collective behaviors as gossiping, ostracism, banishment, and even, in extreme cases, execution. “In egalitarian hierarchies the pyramid of power is turned upside down,” Boehm explains, “with a politically united rank and file dominating the alpha-male types” (66).

The implications for theories about our ancestors are profound. The groups humans were living in as they evolved the traits that made them what we recognize today as human were highly motivated and well-equipped to both prevent and when necessary punish the type of free-riding that evolutionary psychologists and other selfish gene theorists insist would undermine group cohesion. Boehm makes this point explicit, writing,

The overall hypothesis is straightforward: basically, the advent of egalitarianism shifted the balance of forces within natural selection so that within-group selection was substantially debilitated and between-group selection was amplified. At the same time, egalitarian moral communities found themselves uniquely positioned to suppress free-riding… at the level of phenotype. With respect to the natural selection of behavior genes, this mechanical formula clearly favors the retention of altruistic traits. (199)

This is the point where he picks up the argument again in Moral Origins. The story of the homicidal man named /Twi is an extreme example of the predictable results of overly aggressive behaviors. Any nomadic forager who intransigently tries to throw his weight around the way alpha male chimpanzees do will probably end up getting “porcupined” (158) like /Twi and the three men depicted in the Magdalenian cave art in Spain.

Murder is an extreme example of the types of free-riding behavior that nomadic foragers reliably sanction. Any politically overbearing treatment of group mates, particularly the issuing of direct commands, is considered a serious moral transgression. But alongside this disapproval of bossy or bullying behavior there exists an ethic of sharing and generosity, so people who are thought to be stingy are equally disliked. As Boehm writes in Hierarchy in the Forest, “Politically egalitarian foragers are also, to a significant degree, materially egalitarian” (70). The image many of us grew up with of the lone prehistoric male hunter going out to stalk his prey, bringing it back as a symbol of his prowess in hopes of impressing beautiful and fertile females, turns out to be completely off-base. In most hunter-gather groups, the males hunt in teams, and whatever they kill gets turned over to someone else who distributes the meat evenly among all the men so each of their families gets an equal portion. In some cultures, “the hunter who made the kill gets a somewhat larger share,” Boehm writes in Moral Origins, “perhaps as an incentive to keep him at his arduous task” (185). But every hunter knows that most of the meat he procures will go to other group members—and the sharing is done without any tracking of who owes whom a favor. Boehm writes,

The models tell us that the altruists who are helping nonkin more than they are receiving help must be “compensated” in some way, or else they—meaning their genes—will go out of business. What we can be sure of is that somehow natural selection has managed to work its way around these problems, for surely humans have been sharing meat and otherwise helping others in an unbalanced fashion for at least 45,000 years. (184)

Following biologist Richard Alexander, Boehm sees this type of group beneficial generosity as an example of “indirect reciprocity.” And he believes it functions as a type of insurance policy, or, as anthropologists call it, “variance reduction.” It’s often beneficial for an individual’s family to pay in, as it were, but much of the time people contribute knowing full well the returns will go to others.

Less extreme cases than the psychopaths who end up porcupined involve what Boehm calls “meat-cheaters.” A prominent character in Moral Origins is an Mbuti Pygmy man named Cephu, whose story was recounted in rich detail by the anthropologist Colin Turnbull. One of the cooperative hunting strategies the Pygmies use has them stretching a long net through the forest while other group members create a ruckus to scare animals into it. Each net holder is entitled to whatever runs into his section of the net, which he promptly spears to death. What Cephu did was sneak farther ahead of the other men to improve his chances of having an animal run into his section of the net before the others. Unfortunately for him, everyone quickly realized what was happening. Returning to the camp after depositing his ill-gotten gains in his hut, Cephu hears someone call out that he is an animal. Beyond that, everyone was silent. Turnbull writes,

Cephu walked into the group, and still nobody spoke. He went to where a youth was sitting in a chair. Usually he would have been offered a seat without his having to ask, and now he did not dare to ask, and the youth continued to sit there in as nonchalant a manner as he could muster. Cephu went to another chair where Amabosu was sitting. He shook it violently when Amabosu ignored him, at which point he was told, “Animals lie on the ground.” (Quoted 39)

Thus began the accusations. Cephu burst into tears and tried to claim that his repositioning himself in the line was an accident. No one bought it. Next, he made the even bigger mistake of trying to suggest he was entitled to his preferential position. “After all,” Turnbull writes, “was he not an important man, a chief, in fact, of his own band?” At this point, Manyalibo, who was taking the lead in bringing Cephu to task, decided that the matter was settled. He said that

there was obviously no use prolonging the discussion. Cephu was a big chief, and Mbuti never have chiefs. And Cephu had his own band, of which he was chief, so let him go with it and hunt elsewhere and be a chief elsewhere. Manyalibo ended a very eloquent speech with “Pisa me taba” (“Pass me the tobacco”). Cephu knew he was defeated and humiliated. (40)

The guilty verdict Cephu had to accept to avoid being banished from the band came with the sentence that he had to relinquish all the meat he brought home that day. His attempt at free-riding therefore resulted not only in a loss of food but also in a much longer-lasting blow to his reputation.

Boehm has built a large database from ethnographic studies like Lee’s and Turnbull’s, and it shows that in their handling of meat-cheaters and self-aggrandizers nomadic foragers all over the world use strategies similar to those of the Pygmies. First comes the gossip about your big ego, your dishonesty, or your cheating. Soon you’ll recognize a growing reluctance of other’s to hunt with you, or you’ll have a tough time wooing a mate. Next, you may be directly confronted by someone delegated by a quorum of group members. If you persist in your free-riding behavior, especially if it entails murder or serious attempts at domination, you’ll probably be ambushed and turned into a porcupine. Alexander put forth the idea of “reputational selection,” whereby individuals benefit in terms of survival and reproduction from being held in high esteem by their group mates. Boehm prefers the term “social selection,” however, because it encompasses the idea that people are capable of figuring out what’s best for their groups and codifying it in their culture. How well an individual internalizes a group’s norms has profound effects on his or her chances for survival and reproduction. Boehm’s theory is that our consciences are the mechanisms we’ve evolved for such internalization.

Though there remain quite a few chicken-or-egg conundrums to work out, Boehm has cobbled together archeological evidence from butchering cites, primatological evidence from observations of apes in the wild and in captivity, and quantitative analyses of ethnographic records to put forth a plausible history of how our consciences evolved and how we became so concerned for the well-being of people we may barely know. As humans began hunting larger game, demanding greater coordination and more effective long-distance killing tools, an already extant resentment of alphas expressed itself in collective suppression of bullying behavior. And as our developing capacity for language made it possible to keep track of each other’s behavior long-term it started to become important for everyone to maintain a reputation for generosity, cooperativeness, and even-temperedness. Boehm writes,

Ultimately, the social preferences of groups were able to affect gene pools profoundly, and once we began to blush with shame, this surely meant that the evolution of conscientious self-control was well under way. The final result was a full-blown, sophisticated modern conscience, which helps us to make subtle decisions that involve balancing selfish interests in food, power, sex, or whatever against the need to maintain a decent personal moral reputation in society and to feel socially valuable as a person. The cognitive beauty of having such a conscience is that it directly facilitates making useful social decisions and avoiding negative social consequences. Its emotional beauty comes from the fact that we in effect bond with the values and rules of our groups, which means we can internalize our group’s mores, judge ourselves as well as others, and, hopefully, end up with self-respect. (173)

Social selection is actually a force that acts on individuals, selecting for those who can most strategically suppress their own selfish impulses. But in establishing a mechanism that guards the group norm of cooperation against free riders, it increased the potential of competition between groups and quite likely paved the way for altruism of the sort Leacock’s informant Thomas displayed. Boehm writes,

Thomas surely knew that if he turned down the pair of hungry men, they might “bad-mouth” him to people he knew and thereby damage his reputation as a properly generous man. At the same time, his costly generosity might very well be mentioned when they arrived back in their camp, and through the exchange of favorable gossip he might gain in his public esteem in his own camp. But neither of these socially expedient personal considerations would account for the “dead” feeling he mentioned with such gravity. He obviously had absorbed his culture’s values about sharing and in fact had internalized them so deeply that being selfish was unthinkable. (221)

In response to Ghiselin’s cynical credo, “Scratch an altruist and watch a hypocrite bleed,” Boehm points out that the best way to garner the benefits of kindness and sympathy is to actually be kind and sympathetic. He points out further that if altruism is being selected for at the level of phenotypes (the end-products of genetic processes) we should expect it to have an impact at the level of genes. In a sense, we’ve bred altruism into ourselves. Boehm writes,

If such generosity could be readily faked, then selection by altruistic reputation simply wouldn’t work. However, in an intimate band of thirty that is constantly gossiping, it’s difficult to fake anything. Some people may try, but few are likely to succeed. (189)

The result of the social selection dynamic that began all those millennia ago is that today generosity is in our bones. There are of course circumstances that can keep our generous impulses from manifesting themselves, and those impulses have a sad tendency to be directed toward members of our own cultural groups and no one else. But Boehm offers a slightly more optimistic formula than Ghiselin’s:

I do acknowledge that our human genetic nature is primarily egoistic, secondarily nepotistic, and only rather modestly likely to support acts of altruism, but the credo I favor would be “Scratch an altruist, and watch a vigilant and successful suppressor of free riders bleed. But watch out, for if you scratch him too hard, he and his group may retaliate and even kill you. (205)

Read Part 1:

A CRASH COURSE IN MULTI-LEVEL SELECTION THEORY: PART 1-THE GROUNDWORK LAID BY DAWKINS AND GOULD

And Part 2:

Also of interest:

A Crash Course in Multilevel Selection Theory part 2: Steven Pinker Falls Prey to the Averaging Fallacy Sober and Wilson Tried to Warn Him about

Eliot Sober and David Sloan Wilson’s “Unto Others” lays out a theoretical framework for how selection at the level of the group could have led to the evolution of greater cooperation among humans. They point out the mistake many theorists make in thinking because evolution can be defined as changes in gene frequencies, it’s only genes that matter. But that definition leaves aside the question of how traits and behaviors evolve, i.e. what dynamics lead to the changes in gene frequencies. Steven Pinker failed to grasp their point.

If you were a woman applying to graduate school at the University of California at Berkeley in 1973, you would have had a 35 percent chance of being accepted. If you were a man, your chances would have been significantly better. Forty-four percent of male applicants got accepted that year. Apparently, at this early stage of the feminist movement, even a school as notoriously progressive as Berkeley still discriminated against women. But not surprisingly, when confronted with these numbers, the women of the school were ready to take action to right the supposed injustice. After a lawsuit was filed charging admissions offices with bias, however, a department-by-department examination was conducted which produced a curious finding: not a single department admitted a significantly higher percentage of men than women. In fact, there was a small but significant trend in the opposite direction—a bias against men.

What this means is that somehow the aggregate probability of being accepted into grad school was dramatically different from the probabilities worked out through disaggregating the numbers with regard to important groupings, in this case the academic departments housing the programs assessing the applications. This discrepancy called for an explanation, and statisticians had had one on hand since 1951.

This paradoxical finding fell into place when it was noticed that women tended to apply to departments with low acceptance rates. To see how this can happen, imagine that 90 women and 10 men apply to a department with a 30 percent acceptance rate. This department does not discriminate and therefore accepts 27 women and 3 men. Another department, with a 60 percent acceptance rate, receives applications from 10 women and 90 men. This department doesn’t discriminate either and therefore accepts 6 women and 54 men. Considering both departments together, 100 men and 100 women applied, but only 33 women were accepted, compared with 57 men. A bias exists in the two departments combined, despite the fact that it does not exist in any single department, because the departments contribute unequally to the total number of applicants who are accepted. (25)

This is how the counterintuitive statistical phenomenon known as Simpson’s Paradox is explained by philosopher Elliott Sober and biologist David Sloan Wilson in their 1998 book Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior, in which they argue that the same principle can apply to the relative proliferation of organisms in groups with varying percentages of altruists and selfish actors. In this case, the benefit to the group of having more altruists is analogous to the higher acceptance rates for grad school departments which tend to receive a disproportionate number of applications from men. And the counterintuitive outcome is that, in an aggregated population of groups, altruists have an advantage over selfish actors—even though within each of those groups selfish actors outcompete altruists.

Sober and Wilson caution that this assessment is based on certain critical assumptions about the population in question. “This model,” they write, “requires groups to be isolated as far as the benefits of altruism are concerned but nevertheless to compete in the formation of new groups” (29). It also requires that altruists and nonaltruists somehow “become concentrated in different groups” (26) so the benefits of altruism can accrue to one while the costs of selfishness accrue to the other. One type of group that follows this pattern is a family, whose members resemble each other in terms of their traits—including a propensity for altruism—because they share many of the same genes. In humans, families tend to be based on pair bonds established for the purpose of siring and raising children, forming a unit that remains stable long enough for the benefits of altruism to be of immense importance. As the children reach adulthood, though, they disperse to form their own family groups. Therefore, assuming families live in a population with other families, group selection ought to lead to the evolution of altruism.

Sober and Wilson wrote Unto Others to challenge the prevailing approach to solving mysteries in evolutionary biology, which was to focus strictly on competition between genes. In place of this exclusive attention on gene selection, they advocate a pluralistic approach that takes into account the possibility of selection occurring at multiple levels, from genes to individuals to groups. This is where the term multilevel selection comes from. In certain instances, focusing on one level instead of another amounts to a mere shift in perspective. Looking at families as groups, for instance, leads to many of the same conclusions as looking at them in terms of vehicles for carrying genes.

William D. Hamilton, whose thinking inspired both Richard Dawkins’ Selfish Gene and E.O. Wilson’s Sociobiology, long ago explained altruism within families by setting forth the theory of kin selection, which posits that family members will at times behave in ways that benefit each other even at their own expense because the genes underlying the behavior don’t make any distinction between the bodies which happen to be carrying copies of themselves. Sober and Wilson write,

As we have seen, however, kin selection is a special case of a more general theory—a point that Hamilton was among the first to appreciate. In his own words, “it obviously makes no difference if altruists settle with altruists because they are related… or because they recognize fellow altruists as such, or settle together because of some pleiotropic effect of the gene on habitat preference.” We therefore need to evaluate human social behavior in terms of the general theory of multilevel selection, not the special case of kin selection. When we do this, we may discover that humans, bees, and corals are all group-selected, but for different reasons. (134)

A general proclivity toward altruism based on section at the level of family groups may look somewhat different from kin-selected altruism targeted solely at those who are recognized as close relatives. For obvious reasons, the possibility of group selection becomes even more important when it comes to explaining the evolution of altruism among unrelated individuals.

We have to bear in mind that Dawkins’s selfish genes are only selfish with regard to concerning themselves with nothing but ensuring their own continued existence—by calling them selfish he never meant to imply they must always be associated with selfishness as a trait of the bodies they provide the blueprints for. Selfish genes, in other words, can sometimes code for altruistic behavior, as in the case of kin selection. So the question of what level selection operates on is much more complicated than it would be if the gene-focused approach predicted selfishness while the multilevel approach predicted altruism. But many strict gene selection advocates argue that because selfish gene theory can account for altruism in myriad ways there’s simply no need to resort to group selection. Evolution is, after all, changes over time in gene frequencies. So why should we look to higher levels?

Sober and Wilson demonstrate that if you focus on individuals in their simple model of predominantly altruistic groups competing against predominantly selfish groups you will conclude that altruism is adaptive because it happens to be the trait that ends up proliferating. You may add the qualifier that it’s adaptive in the specified context, but the upshot is that from the perspective of individual selection altruism outcompetes selfishness. The problem is that this is the same reasoning underlying the misguided accusations against Berkley; for any individual in that aggregate population, it was advantageous to be a male—but there was never any individual selection pressure against females. Sober and Wilson write,

The averaging approach makes “individual selection” a synonym for “natural selection.” The existence of more than one group and fitness differences between the groups have been folded into the definition of individual selection, defining group selection out of existence. Group selection is no longer a process that can occur in theory, so its existence in nature is settled a priori. Group selection simply has no place in this semantic framework. (32)

Thus, a strict focus on individuals, though it may appear to fully account for the outcome, necessarily obscures a crucial process that went into producing it. The same logic might be applicable to any analysis based on gene-level accounting. Sober and Wilson write that

if the point is to understand the processes at work, the resultant is not enough. Simpson’s paradox shows how confusing it can be to focus only on net outcomes without keeping track of the component causal factors. This confusion is carried into evolutionary biology when the separate effects of selection within and between groups are expressed in terms of a single quantity. (33)

They go on to label this approach “the averaging fallacy.” Acknowledging that nobody explicitly insists that group selection is somehow impossible by definition, they still find countless instances in which it is defined out of existence in practice. They write,

Even though the averaging fallacy is not endorsed in its general form, it frequently occurs in specific cases. In fact, we will make the bold claim that the controversy over group selection and altruism in biology can be largely resolved simply by avoiding the averaging fallacy. (34)

Unfortunately, this warning about the averaging fallacy continues to go unheeded by advocates of strict gene selection theories. Even intellectual heavyweights of the caliber of Steven Pinker fall into the trap. In a severely disappointing essay published just last month at Edge.org called “The False Allure of Group Selection,” Pinker writes

If a person has innate traits that encourage him to contribute to the group’s welfare and as a result contribute to his own welfare, group selection is unnecessary; individual selection in the context of group living is adequate. Individual human traits evolved in an environment that includes other humans, just as they evolved in environments that include day-night cycles, predators, pathogens, and fruiting trees.

Multilevel selectionists wouldn’t disagree with this point; they would readily explain traits that benefit everyone in the group at no cost to the individuals possessing them as arising through individual selection. But Pinker here shows his readiness to fold the process of group competition into some generic “context.” The important element of the debate, of course, centers on traits that benefit the group at the expense of the individual. Pinker writes,

Except in the theoretically possible but empirically unlikely circumstance in which groups bud off new groups faster than their members have babies, any genetic tendency to risk life and limb that results in a net decrease in individual inclusive fitness will be relentlessly selected against. A new mutation with this effect would not come to predominate in the population, and even if it did, it would be driven out by any immigrant or mutant that favored itself at the expense of the group.

But, as Sober and Wilson demonstrate, those self-sacrificial traits wouldn’t necessarily be selected against in the population. In fact, self-sacrifice would be selected for if that population is an aggregation of competing groups. Pinker fails to even consider this possibility because he’s determined to stick with the definition of natural selection as occurring at the level of genes.

Indeed, the centerpiece of Pinker’s argument against group selection in this essay is his definition of natural selection. Channeling Dawkins, he writes that evolution is best understood as competition between “replicators” to continue replicating. The implication is that groups, and even individuals, can’t be the units of selection because they don’t replicate themselves. He writes,

The theory of natural selection applies most readily to genes because they have the right stuff to drive selection, namely making high-fidelity copies of themselves. Granted, it's often convenient to speak about selection at the level of individuals, because it’s the fate of individuals (and their kin) in the world of cause and effect which determines the fate of their genes. Nonetheless, it’s the genes themselves that are replicated over generations and are thus the targets of selection and the ultimate beneficiaries of adaptations.