READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

Why the Critics Are Getting Luhrmann's Great Gatsby so Wrong

There’s something fitting about the almost even split among the movie critics sampled on Rotten Tomatoes—and the much larger percentage of lay viewers who liked the movie (48% vs. 84% as of now). This is because, like the novel itself, Luhrmann’s vision of Gatsby is visionary, and, as Denby points out, when the novel was first published it was panned by most critics.

I doubt I’m the only one who had to be told at first that The Great Gatsby was a great book. Reading it the first time, you’re guaranteed to miss at least two-thirds of the nuance—and the impact of the story, its true greatness, lies in the very nuance that’s being lost on you. Take, for instance, the narrator Nick Carraway’s initial assessment of the title character. After explaining that his habit of open-minded forbearance was taken to its limit and beyond by the events of the past fall he’s about to recount, he writes, “Only Gatsby, the man who gives his name to this book, was exempt from my reaction—Gatsby who represented everything for which I have an unaffected scorn.” Already we see that Nick’s attitude toward Gatsby is complicated, and even though we can eventually work out that his feelings toward his neighbor are generally positive, at least compared to his feelings for the other characters comprising that famously “rotten crowd,” it’s still hard tell what he really thinks of the man.

When I first saw the previews for the Baz Luhrmann movie featuring Leonardo DiCaprio as Gatsby, I was—well, at first, I was excited, thrilled even. Then came the foreboding. This movie, I was sure, was going to do unspeakable violence to all that nuance, make of it a melodrama that would all but inevitably foreclose on any opportunity for the younger, more vulnerable generation to experience a genuine connection with the story through Nick’s morally, linguistically, existentially tangled telling—contenting them instead with a pop culture cartoon. This foreboding was another thing I wasn’t alone in. David Denby ends his uncharacteristically shaky review in The New Yorker,

Will young audiences go for this movie, with its few good scenes and its discordant messiness? Luhrmann may have miscalculated. The millions of kids who have read the book may not be eager for a flimsy phantasmagoria. They may even think, like many of their elders, that “The Great Gatsby” should be left in peace. The book is too intricate, too subtle, too tender for the movies. Fitzgerald’s illusions were not very different from Gatsby’s, but his illusionless book resists destruction even from the most aggressive and powerful despoilers.

Since Denby’s impulse to protect the book from despoiling so perfectly mirrored my own, I had to wonder in the interval between reading his review and seeing the movie myself if he had settled on this sentiment before or after he’d seen it.

The Great Gatsby is a novel that rewards multiple re-readings like very few others. You don’t simply re-experience it as you might expect; rather, each time feels as if you’re discovering something new, having a richer, more devastating experience than ever before. This investment of time and attention coupled with the sense after each reading of having finally reached some definitive appreciation for the book gives enthusiasts a proprietary attitude toward it. We sneer at tyros who claim to understand its greatness but can’t possibly fathom its deeper profundities the way we do. The main charge so far leveled against Luhrmann by movie critics is that he’s a West Egg tourist—a charge that can only be made convincingly by us natives. This is captured nowhere so well as in the title of Linda Holmes’s review on NPR’s website, “Loving ‘Gatsby’ Too Much and Not Enough.’” (Another frequent criticism focuses on the anachronistic music, as if the critics were afraid we might be tricked into believing Jay-Z harks to the Jazz Age.)

There’s something fitting about the almost even split among the movie critics sampled on Rotten Tomatoes—and the much larger percentage of lay viewers who liked the movie (48% vs. 84% as of now). This is because, like the novel itself, Luhrmann’s vision of Gatsby is visionary, and, as Denby points out, when the novel was first published it was panned by most critics. The Rotten Tomatoes headline says

the consensus among critics is that movie is “a Case of Style over Substance,” and the main blurb concludes, “The pundits say The Great Gatsby never lacks for spectacle, but what’s missing is the heart beneath the glitz.”

That wasn’t my experience at all, and I’d wager this pronouncement is going to baffle most people who see the movie.

Let’s face it, Luhrmann was in a no-win situation. His movie fails to capture Fitzgerald’s novel in all its nuance, but that was inevitable. The question is, does the movie convey something of the essence of the novel? Another important question, though I’m at risk of literary blasphemy merely posing it, is whether the movie contributes anything of value to the story, some added dimension, some more impactful encounter with the characters, a more visceral experience of some of the scenes? Cinema can’t do justice to the line-by-line filigree of literature, but it can offer audiences a more immediate and immersive simulation of actual presence in the scenes. And this is what Luhrmann contributes as reparation for all the paved over ironic niceties of Fitzgerald’s language. Denby, a literature-savvy film critic, is breathtakingly oblivious to this fundamental difference between the two media, writing of one of the parties,

Fitzgerald’s scene at the apartment gives off a feeling of sinister incoherence; Luhrmann’s version is merely a frantic jumble. The picture is filled with an indiscriminant swirling motion, a thrashing impress of “style” (Art Deco turned to digitized glitz), thrown at us with whooshing camera sweeps and surges and rapid changes of perspective exaggerated by 3-D.

Thus Denby reveals that he’s either never been drunk or that it’s been so long since he was that he doesn’t remember. The woman I saw the movie with and I both made jokes along the lines of “I think I was at that party.”

Here’s where I reveal my own literary snobbishness by suggesting that it’s not Luhrmann and his screenwriter Craig Pearce who miss the point of the novel—or at least one of its points—but The Great Denby himself, and all the other critics of his supposedly native West Egg ilk. No one argues that the movie doesn’t do justice to the theme of America’s false promise of social mobility and the careless depredations of the established rich on the nouveau riche. The charge is that there’s too much glitz, too much chaos, incoherence, fleeting swirling passes of the 3-D lens and, oh yeah, hip-hop music. The other crucial theme—or maybe it’s the same theme—of The Great Gatsby isn’t portrayed in this hectic collage of glittering excess. But that’s because instead of portraying it, Luhrmann simulates it for us. Fitzgerald’s novel isn’t “illusionless,” as Denby insists; it’s all about illusions. It’s all about the stories people tell, those stories which Nick complains are so often “plagiaristic and marred by obvious suppression”—a complaint he voices as soon as the third paragraph of the novel. We’re not meant, either in Fitzgerald’s rendition or Luhrmann’s, to watch as reality plays out in some way that’s intended to seem natural—we’re meant to experience the story as a dream, a fantasy that keeps getting frayed and interrupted before ultimately being dashed by the crashing tide of reality.

The genius of Luhrmann’s contribution lies in his recognition of The Great Gatsby as a story about the collision of a dream with the real world. The beginning of the movie is chaotic and swirling, a bit like a night of drunkenness at an extravagant party. But then there are scenes that are almost painfully real, like the one featuring the final confrontation between Gatsby and Tom Buchannan, the scene which Denby describes as “the dramatic highlight of this director’s career.” And for all the purported lack of heart in this swirling dreamworld I was struck by how many times I found myself being choked up as I watched it. Nick’s final farewell to Gatsby in the movie actually does Fitzgerald one better (yeah, I said it).

The bad reviews are nothing but the supercilious preening of literature snobs (I probably would’ve written a similar one myself if I hadn’t read so many before seeing the movie). The movie is of course no substitute for the book. Both Nick and Daisy come across more sympathetically, but though this subtly changes the story it still works in its own way. Luhrmann’s Great Gatsby is a fine, even visionary complement to Fitzgerald’s. Ten years from now there may be another film version, and it will probably strike a completely different tone—but it could still be just as successful, contribute just as much. That’s the thing with these dreams and stories—they’re impossible to nail down with finality.

Also read

HOW TO GET KIDS TO READ LITERATURE WITHOUT MAKING THEM HATE IT

T.J. Eckleburg Sees Everything: The Great God-Gap in Gatsby part 2 of 2

The simple explanation for Fitzgerald’s decision not to gratify his readers but rather to disappoint and disturb them is that he wanted his novel to serve as an indictment of the types of behavior that are encouraged by the social conditions he describes in the story, conditions which would have been easily recognizable to many readers of his day and which persist into the Twenty-First Century.

Though The Great Gatsby does indeed tell a story of punishment, readers are left with severe doubts as to whether those who receive punishment actually deserve it. Gatsby is involved in criminal activities, and he has an affair with a married woman. Myrtle likewise is guilty of adultery. But does either deserve to die? What about George Wilson? His is the only attempt in the novel at altruistic punishment. So natural is his impulse toward revenge, however, and so given are readers to take that impulse for granted, that its function in preserving a broader norm of cooperation requires explanation. Flesch describes a series of experiments in the field of game theory centering on an exchange called the ultimatum game. One participant is given a sum of money and told he or she must propose a split with a second participant, with the proviso that if the second person rejects the cut neither will get to keep anything. Flesch points out, however, that

It is irrational for the responder not to accept any proposed split from the proposer. The responder will always come out better by accepting than by vetoing. And yet people generally veto offers of less than 25 percent of the original sum. This means they are paying to punish. They are giving up a sure gain in order to punish the selfishness of the proposer. (31)

To understand why George’s attempt at revenge is altruistic, consider that he had nothing to gain, from a purely selfish and rational perspective, and much to lose by killing the man he believed killed his wife. He was risking physical harm if a fight ensued. He was risking arrest for murder. Yet if he failed to seek revenge readers would likely see him as somehow less than human. His quest for justice, as futile and misguided as it is, would likely endear him to readers—if the discovery of how futile and misguided it was didn’t precede their knowledge of it taking place. Readers, in fact, would probably respond more favorably toward George than any other character in the story, including the narrator. But the author deliberately prevents this outcome from occurring.

The simple explanation for Fitzgerald’s decision not to gratify his readers but rather to disappoint and disturb them is that he wanted his novel to serve as an indictment of the types of behavior that are encouraged by the social conditions he describes in the story, conditions which would have been easily recognizable to many readers of his day and which persist into the Twenty-First Century. Though the narrator plays the role of second-order free-rider, the author clearly signals his own readiness to punish by publishing his narrative about such bad behavior perpetrated by characters belonging to a particular group of people, a group corresponding to one readers might encounter outside the realm of fiction.

Fitzgerald makes it obvious in the novel that beyond Tom’s simple contempt for George there exist several more severe impediments to what biologists would call group cohesion but that most readers would simply refer to as a sense of community. The idea of a community as a unified entity whose interests supersede those of the individuals who make it up is something biological anthropologists theorize religion evolved to encourage. In his book Darwin’s Cathedral, in which he attempts to explain religion in terms of group selection theory, David Sloan Wilson writes:

A group of people who abandon self-will and work tirelessly for a greater good will fare very well as a group, much better than if they all pursue their private utilities, as long as the greater good corresponds to the welfare of the group. And religions almost invariably do link the greater good to the welfare of the community of believers, whether an organized modern church or an ethnic group for whom religion is thoroughly intermixed with the rest of their culture. Since religion is such an ancient feature of our species, I have no problem whatsoever imagining the capacity for selflessness and longing to be part of something larger than ourselves as part of our genetic and cultural heritage. (175)

One of the main tasks religious beliefs evolved to handle would have been addressing the same “free-rider problem” William Flesch discovers at the heart of narrative. What religion offers beyond the social monitoring of group members is the presence of invisible beings whose concerns are tied to the collective concerns of the group.

Obviously, Tom Buchanan’s sense of community has clear demarcations. “Civilization is going to pieces,” he warns Nick as prelude to his recommendation of a book titled “The Rise of the Coloured Empires.” “The idea,” Tom explains, “is that if we don’t look out the white race will be—will be utterly submerged” (17). “We’ve got to beat them down,” Daisy helpfully, mockingly chimes in (18). While this animosity toward members of other races seems immoral at first glance, in the social context the Buchanans inhabit it actually represents a concern for the broader group, “the white race.” But Tom’s animosity isn’t limited to other races. What prompts Catherine to tell Nick how her sister “can’t stand” her husband during the gathering in Tom and Myrtle’s apartment is in fact Tom’s ridiculing of George. In response to another character’s suggestion that he’d like to take some photographs of people in Long Island “if I could get the entry,” Tom jokingly insists to Myrtle that she should introduce the man to her husband. Laughing at his own joke, Tom imagines a title for one of the photographs: “‘George B. Wilson at the Gasoline Pump,’ or something like that” (37). Disturbingly, Tom’s contempt for George based on his lowly social status has contaminated Myrtle as well. Asked by her sister why she married George in the first place, she responds, “I married him because I thought he was a gentleman…I thought he knew something about breeding but he wasn’t fit to lick my shoe” (39). Her sense of superiority, however, is based on the artificial plan for her and Tom to get married.

That Tom’s idea of who belongs to his own superior community is determined more by “breeding” than by economic success—i.e. by birth and not accomplishment—is evidenced by his attitude toward Gatsby. In a scene that has Tom stopping with two friends, a husband and wife, at Gatsby’s mansion while riding horses, he is shocked when Gatsby shows an inclination to accept an invitation to supper extended by the woman, who is quite drunk. Both the husband and Tom show their disapproval. “My God,” Tom says to Nick, “I believe the man’s coming…Doesn’t he know she doesn’t want him?” (109). When Nick points out that woman just said she did want him, Tom answers, “he won’t know a soul there.” Gatsby’s statement in the same scene that he knows Tom’s wife provokes him, as soon as Gatsby has left the room, to say, “By God, I may be old-fashioned in my ideas but women run around too much these days to suit me. They meet all kinds of crazy fish” (110). In a later scene that has Tom accompanying Daisy, with Nick in tow, to one of Gatsby’s parties, he asks, “Who is this Gatsby anyhow?... Some big bootlegger?” When Nick says he’s not, Tom says, “Well, he certainly must have strained himself to get this menagerie together” (114). Even when Tom discovers that Gatsby and Daisy are having an affair, he still doesn’t take Gatsby seriously. He calls Gatsby “Mr. Nobody from Nowhere” (137), and says, “I’ll be damned if I see how you got within a mile of her unless you brought the groceries to the back door” (138). Once he’s succeeded in scaring Daisy with suggestions of Gatsby’s criminal endeavors, Tom insists the two drive home together, saying, “I think he realizes that his presumptuous little flirtation is over” (142).

When George Wilson looks to the eyes of Dr. Eckleburg in supplication after that very car ride leads to Myrtle’s death, the fact that this “God” is an advertisement, a supplication in its own right to viewers on behalf of the optometrist to boost his business, symbolically implicates the substitution of markets for religion—or a sense of common interest—as the main factor behind Tom’s superciliously careless sense of privilege. The eyes seem such a natural stand-in for an absent God that it’s easy to take the symbolic logic for granted without wondering why George might mistake them as belonging to some sentient agent. Evolutionary psychologist Jesse Bering takes on that very question in The God Instinct: The Psychology of Souls, Destiny, and the Meaning of Life, where he cites research suggesting that “attributing moral responsibility to God is a sort of residual spillover from our everyday social psychology dealing with other people” (138). Bering theorizes that humans’ tendency to assume agency behind even random physical events evolved as a by-product of our profound need to understand the motives and intentions of our fellow humans: “When the emotional climate is just right, there’s hardly a shape or form that ‘evidence’ cannot assume. Our minds make meaning by disambiguating the meaningless” (99). In place of meaningless events, humans see intentional signs.

According to Bering’s theory, George Wilson’s intense suffering would have made him desperate for some type of answer to the question of why such tragedy has befallen him. After discussing research showing that suffering, as defined by societal ills like infant mortality and violent crime, and “belief in God were highly correlated,” Bering suggests that thinking of hardship as purposeful, rather than random, helps people cope because it allows them to place what they’re going through in the context of some larger design (139). What he calls “the universal common denominator” to all the permutations of religious signs, omens, and symbols, is the same cognitive mechanism, “theory of mind,” that allows humans to understand each other and communicate so effectively as groups. “In analyzing things this way,” Bering writes,

we’re trying to get into God’s head—or the head of whichever culturally constructed supernatural agent we have on offer… This is to say, just like other people’s surface behaviors, natural events can be perceived by us human beings as being about something other than their surface characteristics only because our brains are equipped with the specialized cognitive software, theory of mind, that enables us to think about underlying psychological causes. (79)

So George, in his bereaved and enraged state, looks at a billboard of a pair of eyes and can’t help imagining a mind operating behind them, one whose identity he’s learned to associate with a figure whose main preoccupation is the judgment of individual humans’ moral standings. According to both David Sloan Wilson and Jesse Bering, though, the deity’s obsession with moral behavior is no coincidence.

Covering some of the same game theory territory as Flesch, Bering points out that the most immediate purpose to which we put our theory of mind capabilities is to figure out how altruistic or selfish the people around us are. He explains that

in general, morality is a matter of putting the group’s needs ahead of one’s own selfish interests. So when we hear about someone who has done the opposite, especially when it comes at another person’s obvious expense, this individual becomes marred by our social judgment and grist for the gossip mills. (183)

Having arisen as a by-product of our need to monitor and understand the motives of other humans, religion would have been quickly co-opted in the service of solving the same free-rider problem Flesch finds at the heart of narratives. Alongside our concern for the reputations of others is a close guarding of our own reputations. Since humans are given to assuming agency is involved even in random events like shifts in weather, group cohesion could easily have been optimized with the subtlest suggestion that hidden agents engage in the same type of monitoring as other, fully human members of the group. Bering writes:

For many, God represents that ineradicable sense of being watched that so often flares up in moments of temptation—He who knows what’s in our hearts, that private audience that wants us to act in certain ways at critical decision-making points and that will be disappointed in us otherwise. (191)

Bering describes some of his own research that demonstrates this point. Coincident with the average age at which children begin to develop a theory of mind (around 4), they began responding to suggestions that they’re being watched by an invisible agent—named Princess Alice in honor of Bering’s mother—by more frequently resisting the temptation to avail themselves of opportunities to cheat that were built into the experimental design of a game they were asked to play (Piazza et al. 311-20). An experiment with adult participants, this time told that the ghost of a dead graduate student had been seen in the lab, showed the same results; when competing in a game for fifty dollars, they were much less likely to cheat than others who weren’t told the ghost story (Bering 193).

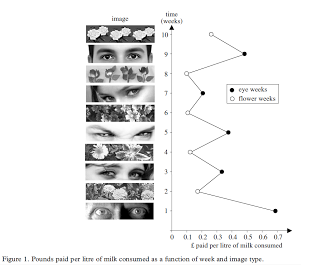

Bering also cites a study that has even more immediate relevance to George Wilson’s odd behavior vis-à-vis Dr. Eckleburg’s eyes. In “Cues of Being Watched Enhance Cooperation in a Real-World Setting,” the authors describe an experiment in which they tested the effects of various pictures placed near an “honesty box,” where people were supposed to be contributing money in exchange for milk and tea. What they found is that when the pictures featured human eyes more people contributed more money than when they featured abstract patterns of flowers. They theorize that

images of eyes motivate cooperative behavior because they induce a perception in participants of being watched. Although participants were not actually observed in either of our experimental conditions, the human perceptual system contains neurons that respond selectively to stimuli involving faces and eyes…, and it is therefore possible that the images exerted an automatic and unconscious effect on the participants’ perception that they were being watched. Our results therefore support the hypothesis that reputational concerns may be extremely powerful in motivating cooperative behavior. (2) (But also see Sparks et al. for failed replications)

This study also suggests that, while Fitzgerald may have meant the Dr. Eckleburg sign as a nod toward religion being supplanted by commerce, there is an alternate reading of the scene that focuses on the sign’s more direct impact on George Wilson. In several scenes throughout the novel, Wilson shows his willingness to acquiesce in the face of Tom’s bullying. Nick describes him as “spiritless” and “anemic” (29). It could be that when he says “God sees everything” he’s in fact addressing himself because he is tempted not to pursue justice—to let the crime go unpunished and thus be guilty himself of being a second-order free-rider. He doesn’t, after all, exert any great effort to find and kill Gatsby, and he kills himself immediately thereafter anyway.

Religion in Gatsby does, of course, go beyond some suggestive references to an empty placeholder. Nick ends the story with a reflection on how “Gatsby believed in the green light,” the light across the bay which he knew signaled Daisy’s presence in the mansion she lived in there. But for Gatsby it was also “the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther… And one fine morning—” (189). Earlier Nick had explained how Gatsby “talked a lot about the past and I gathered that he wanted to recover something, some idea of himself perhaps, that had gone into loving Daisy.” What that idea was becomes apparent in the scene describing Gatsby and Daisy’s first kiss, which occurred years prior to the events of the plot. “He knew that when he kissed this girl, and forever wed his unutterable visions to her perishable breath, his mind would never romp again like the mind of God… At his lips’ touch she blossomed for him like a flower and the incarnation was complete” (117). In place of some mind in the sky, the design Americans are encouraged to live by is one they have created for themselves. Unfortunately, just as there is no mind behind the eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg, the designs many people come up with for themselves are based on tragically faulty premises.

The replacement of religiously inspired moral principles with selfish economic and hierarchical calculations, which Dr. Eckleburg so perfectly represents, is what ultimately leads to all the disgraceful behavior Nick describes. He writes, “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and people and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess” (188). Game theorist and behavioral economist Robert Frank, whose earlier work greatly influenced William Flesch’s theories of narrative, has recently written about how the same social dynamics Fitzgerald lamented are in place again today. In The Darwin Economy, he describes what he calls an “expenditure cascade”:

The explosive growth of CEO pay in recent decades, for example, has led many executives to build larger and larger mansions. But those mansions have long since passed the point at which greater absolute size yields additional utility… Top earners build bigger mansions simply because they have more money. The middle class shows little evidence of being offended by that. On the contrary, many seem drawn to photo essays and TV programs about the lifestyles of the rich and famous. But the larger mansions of the rich shift the frame of reference that defines acceptable housing for the near-rich, who travel in many of the same social circles… So the near-rich build bigger, too, and that shifts the relevant framework for others just below them, and so on, all the way down the income scale. By 2007, the median new single-family house built in the United States had an area of more than 2,300 square feet, some 50 percent more than its counterpart from 1970. (61-2)

How exactly people are straining themselves to afford these houses would be a fascinating topic for Fitzgerald’s successors. But one thing is already abundantly clear: it’s not the CEOs who are cleaning up the mess.

Also read:

HOW TO GET KIDS TO READ LITERATURE WITHOUT MAKING THEM HATE IT

WHY THE CRITICS ARE GETTING LUHRMANN'S GREAT GATSBY SO WRONG

WHY SHAKESPEARE NAUSEATED DARWIN: A REVIEW OF KEITH OATLEY'S "SUCH STUFF AS DREAMS"

T.J. Eckleburg Sees Everything: The Great God-Gap in Gatsby part 1 of 2

So profound is humans’ concern for their reputations that they can even be nudged toward altruistic behaviors by the mere suggestion of invisible witnesses or the simplest representation of watching eyes. The billboard featuring Dr. Eckleburg’s eyes, however, holds no sway over George’s wife Myrtle, or the man she has an affair with. That this man, Tom Buchanan, has such little concern for his reputation—or that he simply feels entitled to exploit Myrtle—serves as an indictment of the social and economic inequality in the America of Fitzgerald’s day.

When George Wilson, in one of the most disturbing scenes in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic The Great Gatsby, tells his neighbor that “God sees everything” while staring disconsolately at the weathered advertisement of some long-ago optometrist named T.J. Eckleburg, his longing for a transcendent authority who will mete out justice on his behalf pulls at the hearts of readers who realize his plea will go unheard. Anthropologists and psychologists studying the human capacity for cooperation and altruism are coming to view religion as an important factor in our evolution. Since the cooperative are always at risk of being exploited by the selfish, mechanisms to enforce altruism had to be in place for any tendency to behave for the benefit of others to evolve. The most basic of these mechanisms is a constant awareness of our own and our neighbors’ reputations. Humans, research has shown, are far more tempted to behave selfishly when they believe it won’t harm their reputations—i.e. when they believe no witnesses are present.

So profound is humans’ concern for their reputations that they can even be nudged toward altruistic behaviors by the mere suggestion of invisible witnesses or the simplest representation of watching eyes. The billboard featuring Dr. Eckleburg’s eyes, however, holds no sway over George’s wife Myrtle, or the man she has an affair with. That this man, Tom Buchanan, has such little concern for his reputation—or that he simply feels entitled to exploit Myrtle—serves as an indictment of the social and economic inequality in the America of Fitzgerald’s day, which carved society into hierarchically arranged echelons and exposed the have-nots to the careless depredations of the haves.

Nick Carraway, the narrator, begins the story by recounting a lesson he learned from his father as part of his Midwestern upbringing. “Whenever you feel like criticizing anyone,” Nick’s father had told him, “just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had”(5). This piece of wisdom serves at least two purposes: it explains Nick’s self-proclaimed inclination to “reserve all judgments,” highlighting the severity of the wrongdoings which have prompted him to write the story; and it provides an ironic moral lens through which readers view the events of the plot. What is to be made, in light of Nick’s father’s reminder about unevenly parceled out advantages, of the crimes committed by wealthy characters like Tom and Daisy Buchanan?

The focus on morality notwithstanding, religion plays a scant, but surprising, role in The Great Gatsby. It first appears in a conversation between Nick and Catherine, the sister of Myrtle Wilson. Catherine explains to Nick that neither Tom nor Myrtle “can stand the person they’re married to” (37). To the obvious question of why they don’t simply leave their spouses, Catherine responds that it’s Daisy, Tom’s wife, who represents the sole obstacle to the lovers’ happiness. “She’s a Catholic,” Catherine says, “and they don’t believe in divorce” (38). However, Nick explains that “Daisy was not a Catholic,” and he goes on to admit, “I was a little shocked by the elaborateness of the lie.” The conversation takes place at a small gathering hosted by Tom and Myrtle in an apartment rented, it seems, for the sole purpose of giving the two a place to meet. Before Nick leaves the party, he witnesses an argument between the hosts over whether Myrtle has any right to utter Daisy’s name which culminates in Tom striking her and breaking her nose. Obviously, Tom doesn’t despise his wife as much as Myrtle does her husband. And the lie about Daisy’s religious compunctions serves simply to justify Tom’s refusal to leave her and facilitate his continued exploitation of Myrtle.

The only other scene in which a religious belief is asserted explicitly is the one featuring the conversation between George and his neighbor. It comes after Myrtle, whose dalliance had finally aroused her husband’s suspicion, has been struck by a car and killed. George, upon discovering that something had been going on behind his back, locked Myrtle in his garage, and it was when she escaped and ran out into the road to stop the car she thought Tom was driving that she got hit. As the dust from the accident settles—literally, since the garage and the stretch of road are situated in a “valley of ashes” created by the remnants of the coal powering the nearby city being dumped alongside the adjacent rail tracks—George is left alone with a fellow inhabitant of the valley, a man named Michaelis, who asks if he belongs to a church where there might a be a priest he can call to come comfort him. “Don’t belong to one,” George answers (165). He does, however, describe a religious belief of sorts to Michaelis. Having explained why he’d begun to suspect Myrtle was having an affair, George goes on to say, “I told her she might fool me but she couldn’t fool God. I took her to the window.” He walks to the window again as he’s telling the story to his neighbor. “I said, ‘God knows what you’ve been doing, everything you’ve been doing. You may fool me but you can’t fool God!’” (167). Michaelis, who is by now fearing for George’s sanity, notices something disturbing as he stands listening to this rant: “Standing behind him Michaelis saw with a shock that he was looking at the eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg which had just emerged pale and enormous from the dissolving night” (167). When George speaks again, repeating, “God sees everything,” Michaelis feels compelled to assure him, “That’s an advertisement” (167). Though when George first expresses the sentiment, part declaration, part plea, he was clearly thinking of Myrtle’s crime against him, when he repeats it he seems to be thinking of the driver’s crime against Myrtle. God may have seen it, but George takes it upon himself to deliver the punishment.

George Wilson’s turning to God for some moral accounting, despite his general lack of religious devotion, mirrors Nick Carraway’s efforts to settle the question of culpability, despite his own professed reluctance to judge, through the telling of this tragic story. Nick learns from Gatsby that it was in fact Daisy, with whom Gatsby has been carrying on an affair, who was behind the wheel of the car that killed Myrtle. But Gatsby, who was in the passenger seat, assures him it was an accident, not revenge for the affair Myrtle was carrying on with Daisy’s husband. Yet when George finally leaves his garage and turns to Tom to find out who owns the car that killed his wife, assuming it is the same man his wife was cheating on him with, Tom informs him the car belongs to Gatsby, leaving out the crucial fact that Gatsby never met Myrtle. George goes to Gatsby’s mansion, finds him in his pool, shoots and kills him, and then turns the gun on himself. Three people end up dead, Myrtle, George, and Gatsby. Despite their clear complicity, though, Tom and Daisy experience nary a repercussion beyond the natural grief of losing their lovers. Insofar as Nick believes the Buchanans’ perfect getaway is an intolerable injustice, he must realize he holds the power to implicate them, to damage their reputations, by writing and publishing his account of the incidents leading up to the deaths.

Evolutionary critic William Flesch sees our human passion for narrative as a manifestation of our obsession with our own and our fellow humans’ reputations, which evolved at least in part to keep track of each other’s propensities for moral behavior. In Comeuppance: Costly Signaling, Altruistic Punishment, and Other Biological Components of Fiction, Flesch lays out his attempt at solving what he calls “the puzzle of narrative interest,” by which he means the question of why people feel “anxiety on behalf of and about the motives, actions, and experiences of fictional characters” (7). He finds the key to solving this puzzle in a concept called “strong reciprocity,” whereby “the strong reciprocator punishes and rewards others for their behavior toward any member of the social group, and not just or primarily for their individual interactions with the reciprocator” (22). An example of this phenomenon takes place in the novel when the guests at Gatsby’s parties gossip and ardently debate about which of the rumors circling their host are true—particularly of interest is the one saying that “he killed a man” (48). Flesch cites reports from experiments demonstrating that in uneven exchanges, participants with no stake in the outcome are actually willing to incur some cost to themselves in an effort to enforce fairness (31-5). He then goes on to give a compelling account of how this tendency goes a long way toward an explanation of our human fascination with storytelling.

Flesch’s theory of narrative interest begins with models of the evolution of cooperation. For the first groups of human ancestors to evolve cooperative or altruistic traits, they would have had to solve what biologists and game theorists call “the free-rider problem.” Flesch explains:

Darwin himself had proposed a way for altruism to evolve through a mechanism of group selection. Groups with altruists do better as a group than groups without. But it was shown in the 1960s that, in fact, such groups would be too easily infiltrated or invaded by nonaltruists—that is, that group boundaries were too porous—to make group selection strong enough to overcome competition at the level of the individual or the gene. (5)

Strong, or indirect reciprocity, coupled with a selfish concern for one’s own reputation, may have evolved as mechanisms to address this threat of exploitative non-cooperators. For instance, in order for Tom Buchanan to behave selfishly by sleeping with George Wilson’s wife, he had to calculate his chances of being discovered in the act and punished. Interestingly, after “exchanging a frown with Doctor Eckleburg” while speaking to Nick in an early scene in Wilson’s garage, Tom suggests his motives for stealing away with Myrtle are at least somewhat noble. “Terrible place,” he says of the garage and the valley of ashes. “It does her good to get away” (30). Nick, clearly uncomfortable with the position Tom has put him in, where he has to choose whether to object to Tom’s behavior or play the role of second-order free-rider himself, poses the obvious question: “Doesn’t her husband object?” To which Tom replies, “He’s so dumb he doesn’t know he’s alive” (30). Nick, inclined to reserve judgment, keeps Tom and Myrtle’s secret. Later in the novel, though, he keeps the same secret for Daisy and Gatsby.

What makes Flesch’s theory so compelling is that it sheds light on the roles played by everyone from the author, in this case Fitzgerald, to the readers, to the characters, whose nonexistence beyond the pages of the novel is little obstacle to their ability to arouse sympathy or ire. Just as humans are keen to ascertain the relative altruism of their neighbors, so too are they given to broadcasting signals of their own altruism. Flesch explains, “we track not only the original actor whose actions we wish to see reciprocated, whether through reward or more likely punishment; we track as well those who are in a position to track that actor, and we track as well those in a position to track those tracking the actor” (50). What this means is that even if the original “actor” is fictional, readers can signal their own altruism by becoming emotionally engaged in the outcome of the story, specifically by wanting to see altruistic characters rewarded and selfish characters punished.

Nick Carraway is tracking Tom Buchanan’s actions, for instance. Reading the novel, we have little doubt what Nick’s attitude toward Tom is, especially as the story progresses. Though we may favor Nick over Tom, Nick’s failure to sufficiently punish Tom when the degree of his selfishness first becomes apparent tempers any positive feelings we may have toward him. As Flesch points out, “altruism could not sustain an evolutionarily stable system without the contribution of altruistic punishers to punish the free-riders who would flourish in a population of purely benevolent altruists” (66).

On the other hand, through the very act of telling the story, the narrator may be attempting to rectify his earlier moral complacence. According to Flesch’s model of the dynamics of fiction, “The story tells a story of punishment; the story punishes as story; the storyteller represents him- or herself as an altruistic punisher by telling it” (83). However, many readers of Gatsby probably find Nick’s belated punishment insufficient, and if they fail to see the novel as a comment on the real injustice Fitzgerald saw going on around him they would be both confused and disappointed by the way the story ends.

Review of "Building Great Sentences," a "Great Courses" Lecture Series by Brooks Landon

Brooks Landon’s course is well worth the effort and cost, but he makes some interesting suggestions about what constitutes a great sentence. To him, greatness has to do with the structure of the language, but truly great sentences—truly great writing—gets its power from its role as a conveyance of meaning, i.e. the words’ connection to the real world.

You’ve probably received catalogues in the mail advertising “Great Courses.” I’ve been flipping through them for years thinking I should try a couple but have always been turned off by the price. Recently, I saw that they were on sale, and one in particular struck me as potentially worthwhile. “Building Great Sentences: Exploring the Writer’s Craft” is taught by Brooks Landon, who is listed as part of the faculty at the University of Iowa. It turns out, however, he’s not in any way affiliated with the august Creative Writing Workshop, and though he uses several example sentences from literature I’d say his primary audience is people interested in Rhetoric and Composition—and that makes the following criticisms a bit unfair. So let me first say that I enjoyed the lectures and think it well worth the money (about thirty bucks) and time (twenty-four half-hour-long lectures).

Landon is obviously reading from a teleprompter, and he’s standing behind a lectern in what looks like Mr. Roger’s living room decked out to look scholarly. But he manages nonetheless to be animated, enthusiastic, and engaging. He gives plenty of examples of the principles he discusses, all of which appear in text form and are easy to follow—though they do at times veer toward the eye-glazingly excessive.

The star of the show is what Landon calls “cumulative sentences,” those long developments from initial capitalized word through a series of phrases serving as free modifiers, each building on its predecessor, focusing in, panning out, or taking it as a point of departure as the writer moves forward into unexplored territory. After watching several lectures, I went to the novel I’m working on and indeed discovered more than a few instances where I’d seen fit to let my phrases accumulate into a stylistic flourish. The catch is that these instances were distantly placed from one another. Moving from my own work to some stories in the Summer Fiction Issue of The New Yorker, I found the same trend. The vast majority of sentences follow Strunk and White’s dictum to be simple and direct, a point Landon acknowledges. Still, for style and rhetorical impact, the long sentences Landon describes are certainly effective.

Landon and I part ways, though, when it comes to “acrobatic” sentences which “draw attention to themselves.” Giving William Gass a high seat in his pantheon of literary luminaries, Landon explains that “Gass always sees language as a subject every bit as interesting and important as is the referential world his language points to, invokes, or stands for.” While this poststructuralist sentiment seems hard to object to, it misses the point of what language does and how it works. Sentences can call attention to themselves for performing their functions well, but calling attention to themselves should never be one of their functions.

Writers like Gass and Pynchon and Wallace fail in their quixotic undertakings precisely because they perform too many acrobatics. While it is true that many readers, particularly those who appreciate literary as opposed to popular fiction—yes, there is a difference—are attuned to the pleasures of language, luxuriating in precise and lyrical writing, there’s something perverse about fixating on sentences to the exclusion of things like character. Great words in great sentences incorporating great images and suggestive comparisons can make the world in which a story takes place come alive—so much so that the life of the story escapes the page and transforms the way readers see the world beyond it. But the prompt for us to keep reading is not the promise of more transformative language; it’s the anticipation of transforming characters. Great sentences in literature owe their greatness to the moments of inspiration, from tiny observation to earth-shattering epiphany, experienced by the people at the heart of the story. Their transformations become our transformations. And literary language may seem to derive whatever greatness it achieves from precision and lyricism, but at a more fundamental level of analysis it must be recognized that writing must be precise and lyrical in its detailing of the thoughts and observations of the characters readers seek to connect with. This takes us to a set of considerations that transcend the workings of any given sentence.

Landon devotes an entire lecture to the rhythm of prose, acknowledging it must be thought of differently from meter in poetry, but failing to arrive at an adequate, objective definition. I wondered all the while why we speak about rhythm at all when we’re discussing passages that don’t follow one. Maybe the rhythm is variable. Maybe it’s somehow progressive and evolving. Or maybe we should simply find a better word to describe this inscrutable quality of impactful and engaging sentences. I propose grace. Indeed, a singer demonstrates grace by adhering to a precisely measured series of vocal steps. Noting a similar type of grace in writing, we’re tempted to hear it as rhythmical, even though its steps are in no way measured. Grace is that quality of action that leaves audiences with an overwhelming sense of its having been well-planned and deftly executed, well-planned because its deft execution appeared so effortless—but with an element of surprise just salient enough to suggest spontaneity. Grace is a delicate balance between the choreographed and the extemporized.

Grace in writing is achieved insofar as the sequential parts—words, phrases, clauses, sentences, paragraphs, sections, chapters—meet the demands of their surroundings, following one another seamlessly and coherently, performing the function of conveying meaning, in this case of connecting the narrator’s thoughts and experiences to the reader. A passage will strike us as particularly graceful when it conveys a great deal of meaning in a seemingly short chain of words, a feat frequently accomplished with analogies (a point on which Landon is eloquent), or when it conveys a complex idea or set of impressions in a way that’s easily comprehended. I suspect Landon would agree with my definition of grace. But his focus on lyrical or graceful sentences, as opposed to sympathetic or engaging characters—or any of the other aspects of literary writing—precludes him from lighting on the idea that grace can be strategically lain aside for the sake of more immediate connections with the people and events of the story, connections functioning in real-time as the reader’s eyes take in the page.

Sentences in literature like to function mimetically, though this observation goes unmentioned in the lectures. Landon cites the beautifully graceful line from Gatsby,

Slenderly, languidly, their hands set lightly on their hips the two young women preceded us out onto a rosy-colored porch open toward the sunset where four candles flickered on the table in the diminished wind (16).

The multiple L’s roll out at a slow pace, mimicking the women and the scene being described. This is indeed a great sentence. But so too is the later sentence in which Nick Carraway recalls being chagrined upon discovering the man he’s been talking to about Gatsby is in fact Gatsby himself.

Nick describes how Gatsby tried to reassure him: “He smiled understandingly—much more than understandingly.” The first notable thing about this sentence is that it stutters. Even though Nick is remembering the scene at a more comfortable future time, he re-experiences his embarrassment, and readers can’t help but sympathize. The second thing to note is that this one sentence, despite serving as a crucial step in the development of Nick’s response to meeting Gatsby and forming an impression of him, is just that, a step. The rest of the remarkable passage comes in the following sentences:

It was one of those rare smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it, that you may come across four or five times in life. It faced—or seemed to face—the whole external world for an instant, and then concentrated on you with an irresistible prejudice in your favor. It understood you just so far as you wanted to be understood, believed in you as you would like to believe in yourself and assured you that it had precisely the impression of you that, at your best, you hoped to convey. Precisely at that point it vanished—and I was looking at an elegant young rough-neck, a year or two over thirty, whose elaborate formality of speech just missed being absurd. Some time before he introduced himself I’d got a strong impression that he was picking his words with care (52-3).

Beginning with a solecism (“reassurance in it, that…”) that suggests Nick’s struggle to settle on the right description, moving onto another stutter (or seemed to face) which indicates his skepticism creeping in beside his appreciation of the regard, the passage then moves into one of those cumulative passages Landon so appreciates. But then there’s the jarring incongruity of the smile’s vanishing. This is, as far as I can remember, the line that sold me on the book when I first read it. You can really feel Nick’s confusion and astonishment. And the effect is brought about by sentences, an irreducible sequence of them, that are markedly ungraceful. (Dashes are wonderful for those break-ins so suggestive of spontaneity and advance in real-time.)

Also read: