The Criminal Sublime: Walter White's Brutally Plausible Journey to the Heart of Darkness in Breaking Bad

Created with Canva’s Magic Media

Even non-literary folk think they know what Nabokov’s Lolita is about, but if you’ve never read it you really have no idea. If ever a work of literature transcended its topic and confounded any attempt at neat summary, this is it. Over the past half century, many have wondered why a novelist with linguistic talents as prodigious as Nabokov’s would choose to detail the exploits of such an unsavory character—that is, unless he shared his narrator’s unpardonable predilection (he didn’t). But Nabokov knew exactly what he was doing when he created Humbert Humbert, a character uniquely capable of taking readers beyond the edge of the map of normal human existence to where the monsters be. The violation of taboo—of decency—is integral to the peculiar and profound impact of the story. Humbert, in the final scene of the novel, attempts to convey the feeling as he commits one last criminal act:

The road now stretched across open country, and it occurred to me—not by way of protest, not as a symbol, or anything like that, but merely as a novel experience—that since I had disregarded all laws of humanity, I might as well disregard the rules of traffic. So I crossed to the left side of the highway and checked the feeling, and the feeling was good. It was a pleasant diaphragmal melting, with elements of diffused tactility, all this enhanced by the thought that nothing could be nearer to the elimination of basic physical laws than driving on the wrong side of the road. In a way, it was a very spiritual itch. Gently, dreamily, not exceeding twenty miles an hour, I drove on that queer mirror side. Traffic was light. Cars that now and then passed me on the side I had abandoned to them, honked at me brutally. Cars coming towards me wobbled, swerved, and cried out in fear. Presently I found myself approaching populated places. Passing through a red light was like a forbidden sip of Burgundy when I was a child. (306)

Thus begins a passage no brief quotation can begin to do justice to. Nor can you get the effect by flipping directly to the pages. You have to earn it by following Humbert for the duration of his appalling, tragic journey. Along the way, you’ll come to discover that the bizarre fascination the novel inspires relies almost exclusively on the contemptibly unpleasant, sickeningly vulnerable and sympathetic narrator, who Martin Amis (himself a novelist specializing in unsavory protagonists) aptly describes as “irresistible and unforgiveable.” The effect builds over the three hundred odd pages as you are taken deeper and deeper into this warped world of compulsively embraced dissolution, until that final scene whose sublimity is rare even in the annals of great literature. Reading it, experiencing it, you don’t so much hold your breath as you simply forget to breathe.

When Walter White, the chemistry teacher turned meth cook in AMC’s excruciatingly addictive series Breaking Bad, closes his eyes and lets his now iconic Pontiac Aztek, the dull green of dollar bill backdrops, veer into the lane of oncoming traffic in the show’s third season, we are treated to a similar sense of peeking through the veil that normally occludes our view of the abyss, glimpsing the face of a man who has slipped through a secret partition, a man who may never find his way back. Walt, played by Brian Cranston, originally broke bad after receiving a diagnosis of inoperable lung cancer and being told his remaining time on earth would be measurable in months rather than years. After seeing a news report of a drug bust and hearing from his DEA agent brother-in-law Hank how much money is routinely confiscated in such operations, Walt goes on a ride-along to get a closer look. Waiting in the backseat as Hank and his fellow agents raid a house an informant tipped them off to, Walt sees a former underachieving student of his named Jesse (Aaron Paul) sneaking out of the upstairs window of the house next door, where he’d absconded to have sex with his neighbor. Walt keeps his mouth shut, letting Jesse escape, and then searches him out later that night to propose they work together to cook and sell meth. From the outset, Walt’s overriding purpose is to make a wad of cash before his cancer kills him, so his family won’t be left with nothing.

That’s the first plotline and the most immediate source of suspense. The fun of watching the show comes from seeing develop the unlikely and fractious but unbreakably profound friendship between Walt and Jesse—and from seeing how again and again the normally nebbishy Walt manages to MacGyver them both out of ever more impossible situations. The brilliant plotting by show creator Vince Gilligan and his writers is consistently worthy of the seamless and moving performances of the show’s actors. I can’t think of a single episode, or even a single scene, that falls flat. But what makes Breaking Bad more than another in the growing list of shows in the bucket list or middleclass crime genres, what makes it so immanently important, is the aspect of the show dealing with the consequences to Walt’s moral character of his increasing entanglement in the underworld. The imminent danger to his soul reveals itself most tellingly in the first season when he returns to his car after negotiating a deal with Tuco, a murderously amped meth dealer with connections to a Mexican cartel. Jesse had already tried to set up an arrangement, with he and Walt serving as producers and Tuco as distributor, but Tuco, after snorting a sample off the blade of a bowie knife, beat Jesse to a pulp, stealing the pound of meth he’d brought to open the deal.

Walt returns to the same office after seeing Jesse in the hospital and hearing about what happened. After going through the same meticulous screening process and finding himself face to face with Tuco, Walt starts dictating terms, insisting that the crazy cartel guy with all the armed henchmen standing around pay extra for his partner’s pain and suffering. Walt has even brought along what looks like another pound of meth. When Tuco breaks into incredulous laugher, saying, “Let me get this straight: I steal your dope, I beat the piss out of your mule boy, and then you walk in here and bring me more meth?” Walt tells him he’s got one thing wrong. Holding up a large crystal from the bag Tuco has opened on his desk, he says, “This is not meth,” and then throws it against the outside wall of the office. The resultant explosion knocks everyone senseless and sends debris raining down on the street below. As the dust clears, Walter takes up the rest of the bag of fulminated mercury, threatening to kill them all unless Tuco agrees to the deal. He does.

After impassively marching back downstairs, crossing the street to the Aztek, and sidling in, Walt sits alone, digging handfuls of cash out of the bag Tuco handed him. Dropping the money back in the bag, he lifts his clenched fists and growls out a long, triumphant “Yeah!” sounding his barbaric yawp over the steering wheel. And we in the audience can’t help sharing his triumph. He’s not only secured a distributor—albeit a dangerously unstable one—opening the way for him to make that pile of money he wants to leave for his family; he’s also put a big scary bully in his place, making him pay, literally, for what he did to Jesse. At a deeper level, though, we also understand that Walt’s yawp is coming after a long period of him being a “hounded slave”—even though the connection with that other Walt, Walt Whitman, won’t be highlighted until season 3.

The final showdown with Tuco happens in season 2 when he tries to abscond with Walter and Jesse to Mexico after the cops raid his office and arrest all his guys. Once the two hapless amateurs have escaped from the border house where Tuco held them prisoner, Walt has to come up with an explanation for why he’s been missing for so long. He decides to pretend to having gone into a fugue state, which had him mindlessly wandering around for days, leaving him with no memory of where he’d gone. To sell the lie, he walks into a convenience store, strips naked, and stands with a dazed expression in front of the frozen foods. The problem with faking a fugue state, though, is that the doctors they bring you to will be worried that you might go into another one, and so Walt escapes his captor in the border town only to find himself imprisoned again, this time in the hospital. In order to be released, he has to convince a psychiatrist that there’s no danger of recurrence. After confirming with the therapist that he can count on complete confidentiality, Walt confesses that there was no fugue state, explaining that he didn’t really go anywhere but “just ran.” When asked why, he responds,

Doctor, my wife is seven months pregnant with a baby we didn't intend. My fifteen-year old son has cerebral palsy. I am an extremely overqualified high school chemistry teacher. When I can work, I make $43,700 per year. I have watched all of my colleagues and friends surpass me in every way imaginable. And within eighteen months, I will be dead. And you ask why I ran?

Thus he covers his omission of one truth with the revelation of another truth. In the show’s first episode, we see Walt working a side job at a car wash, where his boss makes him leave his regular post at the register to go outside and scrub the tires of a car—which turns out to belong to one of his most disrespectful students. At home, his wife Skyler (played by Anna Gun) insists he tell his boss at the carwash he can’t keep working late. She also nags him for using the wrong credit card to buy printer ink. When Walt’s old friends and former colleagues, Elliott and Gretchen Schwartz, who it seems have gone on to make a mighty fortune thanks in large part to Walt’s contribution to their company, offer to pay for his chemotherapy, Skyler can’t fathom why he would refuse the “charity.” We find out later that Walt and Gretchen were once in a relationship and that he’d left the company indignant with her and Elliott for some reason.

What gradually becomes clear is that, in addition to the indignities he suffers at school and at the car wash, Skyler is subjecting him to the slow boil of her domestic despotism. At one point, after overhearing a mysterious phone call, she star-sixty-nines Jesse, and then confronts Walt with his name. Walt covers the big lie with a small one, telling her that Jesse has been selling him pot. When Skyler proceeds to nag him, Walt, with his growing sense of empowerment, asks her to “climb down out of my ass.” Not willing to cede her authority, she later goes directly to Jesse’s house and demands that he stop selling her husband weed. “Good job wearing the pants in the family,” Jesse jeers at him later. But it’s not just Walt she pushes around; over the first four seasons, Skyler never meets a man she doesn’t end up bullying, and she has the maddening habit of insisting on her own reasonableness and moral superiority as she does it.

In a scene from season 1 that’s downright painful to watch, Skyler stages an intervention, complete with a “talking pillow” (kind of like the conch in Lord of the Flies), which she claims is to let all the family members express their feelings about Walt’s decision not to get treatment. Of course, when her sister Marie goes off-message, suggesting chemo might be a horrible idea if Walt’s going to die anyway, Skyler is outraged. The point of the intervention, it becomes obvious, is to convince Walt to swallow his pride and take Elliott and Gretchen’s charity. As Skyler and Marie are busy shouting at each other, Walt finally stands up and snatches the pillow. Just as Marie suggested, he reveals that he doesn’t want to spend his final days in balding, nauseated misery, digging his family into a financial hole only to increase his dismal chances of surviving by a couple percentage points. He goes on,

What I want—what I need—is a choice. Sometimes I feel like I never actually make any of my own. Choices, I mean. My entire life, it just seems I never, you know, had a real say about any of it. With this last one—cancer—all I have left is how I choose to approach this.

This sense of powerlessness is what ends up making Walt dangerous, what makes him feel that all-consuming exultation and triumph every time he outsmarts some intimidating criminal, every time he beats a drug kingpin at his own game. He eventually relents and gets the expensive treatment, but he pays for it his own way, on his own terms. Of course, he can't tell Skyler where the money is really coming from. One of the odd things about watching the show is that you realize during the scenes when Walt is fumblingly trying to get his wife to back off you can’t help hoping he escapes her inquisition so he can go take on one of those scary gun-toting drug dealers again.

One of the ironies that emerge in the two latest seasons is that when Skyler finds out Walt’s been cooking meth her decision not to turn him in is anything but reasonable and moral. She even goes so far as to insist that she be allowed to take part in his illegal activities in the role of a bookkeeper, so she can make sure the laundering of Walt’s money doesn’t leave a trail leading back to the family. Walt already has a lawyer, Saul Goodman (one of the best characters), who takes care of the money, but she can’t stand being left out—so she ends up bullying Saul too. When Walt points out that she doesn’t really need to be involved, that he can continue keeping her in the dark so she can maintain plausible deniability, she scoffs, “I’d rather have them think I’m Bonnie What’s-her-name than some complete idiot.” In spite of her initial reluctance, Skyler reveals she’s just like Walt in her susceptibility to the allure of crime, a weakness borne of disappointment, indignity, and powerlessness. And, her guilt-tripping jabs at Walt for his mendacity notwithstanding, she turns out to be a far better liar than he is—because, as a fiction writer manqué, she actually delights in weaving and enacting convincing tales.

In fact, and not surprising considering the title of the series is Breaking Bad, every one of the main characters—except Walter Jr.—eventually turns to crime. Hank, frustrated at his ongoing failure to track down the source of the mysterious blue meth that keeps turning up on the streets, discovers that Jesse is somehow involved, and then, after Walt and Jesse successfully manage to destroy the telltale evidence, he loses his tempter and beats Jesse so badly he ends up in the hospital again. Marie, Skyler’s sister and Hank’s wife, is a shoplifter, and, after Hank gets shot and sinks into a bitter funk as he recovers, she starts posing as someone looking for a new home, telling elaborate lies about her life story to real estate agents as she pokes around with her sticky fingers in all the houses she visits. Skyler, even before signing on to help with Walt’s money laundering, helps Ted Beneke, the boss she has an affair with, cook his own books so he can avoid paying taxes. Some of the crimes are understandable in terms of harried or slighted people lashing out or acting up. Some of them are disturbing for how reasonably the decision to commit them is arrived at. The most interesting crimes on the show, however, are the ones that are part response to wounded pride and part perfectly reasonable—both motives clear but impossible to disentangle.

The scene that has Walt veering onto the wrong side of the road a la Humbert Humbert occurs in season 3. Walt was delighted when Saul helped him set up an arrangement with Gustavo Fring similar to the one he and Jesse had with Tuco. Gus is a far cooler customer, and far more professional, disguising his meth distribution with his fast-food chicken chain Los Pollos Hermanos. He even hooks Walt up with a fancy underground lab, cleverly hidden beneath an industrial laundry. Walt had learned some time ago that his cancer treatment was working, and he’d already made over a million dollars. But what he comes to realize is that he’s already too deep in the drug producing business, that the only thing keeping him alive is his usefulness to Gus. After a meeting in which he expresses his gratitude, Walt asks Gus if he can continue cooking meth for him. No longer in it just long enough to make money for his family before he dies, Walt drives away, with no idea how long he will live, with an indefinite commitment to keeping up his criminal activities. All his circumstances have changed. The question becomes how Walt will change to adapt to them. He closes his eyes and doesn’t open them until he hears the honk of a semi.

The most moving and compelling scenes in the series are the ones featuring Walt and Jesse’s struggles with their consciences as they’re forced to do increasingly horrible things. Jesse wonders how life can have any meaning at all if someone can do something as wrong as killing another human being and then just go on living like nothing happened. Both Walt and Jesse at times give up caring whether they live or die. Walt is actually so furious after hearing from his doctor that his cancer is in remission that he goes into the men’s room and punches the paper towel dispenser until the dents he’s making become smudged with blood from his knuckles. In season 3, he becomes obsessed with the “contamination” of the meth lab, which turns out to be nothing but a fly. Walt refuses to cook until they catch it, so Jesse sneaks him some sleeping pills to make sure they can finish cooking the day’s batch. In a narcotic haze, Walt reveals how lost and helpless he’s feeling. “I missed it,” he says.

There was some perfect moment that passed me right by. I had to have enough to leave them—that was the whole point. None of this makes any sense if I didn’t have enough. But it had to be before she found out—Skyler. It had to be before that.

“Perfect moment for what?” Jesse asks. “Are you saying you want to die?” Walt responds, “I’m saying I’ve lived too long. –You want them to actually miss you. You want their memories of you to be… But she just won’t understand.”

The theme of every type of human being having the potential to become almost any other type of human being runs throughout the series. Heisenberg, the nom de guerre Walt chooses for himself in the first season, refers to Werner Heisenberg, whose uncertainty principle in quantum mechanics holds that subatomic particles can exist in multiple states simultaneously.

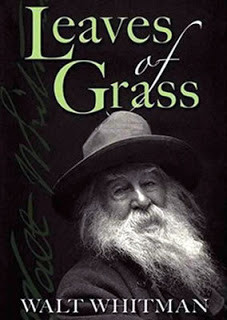

“Song of Myself,” a poem in Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, the one in which he says he is a “hounded slave” and describes how he “sounded my barbaric yawp,” is about how the imagination makes it possible for us to empathize with, and even become, almost anyone. Whitman writes,

“In all people I see myself, none more and not one a barleycorn less/ and the good or bad I say of myself I say of them” (section 20). Another line, perhaps the most famous, reads, “I am large, I contain multitudes” (section 51).

Walter White ends up reading Leaves of Grass in season 3 of Breaking Bad after a lab assistant hired by Gus introduces him to the poem, “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer” to explain his love for the “magic” of chemistry. And in the next season Walt, in one of the only instances where he actually stands up to and silences Skyler, sings a rather surprising song of his own self. When she begins to suspect he’s in imminent danger, she tries to convince him he’s in over his head and that he should go to the police. Having turned away from her, he turns back, almost a different man entirely, and delivers a speech that has already become a standout moment in television history.

Who are you talking to right now? Who is it you think you see? Do you know how much I make a year? I mean, even if I told you, you wouldn’t believe it. Do you know what would happen if I suddenly decided to stop going into work? A business big enough that it could be listed on the Nasdaq goes belly up, disappears—it ceases to exist without me. No, you clearly don’t know who you’re talking to, so let me clue you in. I am not in danger, Skyler—I am the danger. A guy opens his door and gets shot and you think that of me? No, I am the one who knocks.

Just like the mysterious pink teddy bear floating in the White’s pool at the beginning of season 2, half its face scorched, one of its eyes dislodged, Walt turns out to have a very dark side. Though he manages to escape Gus at the end of season 4, the latest season (none of which I’ve seen yet) opens with him deciding to start up his own meth operation. Still, what makes this scene as indelibly poignant as it is shocking (and rousing) is that Walt really is in danger when he makes his pronouncement. He’s expecting to be killed at any moment.

Much of the commentary about the show to date has focused on the questions of just how bad Walt will end up breaking and at what point we will, or at least should, lose sympathy for him. Many viewers, like Emily Nussbaum, jumped ship at the end of season 4 when it was revealed that Walt had poisoned the five-year-old son of Jesse’s girlfriend as part of his intricate ruse to beat Gus. Jesse had been cozying up to Gus, so Walt made it look like he poisoned the kid because he knew his partner went berserk whenever anyone endangered a child. Nussbaum writes,

When Brock was near death in the I.C.U., I spent hours arguing with friends about who was responsible. To my surprise, some of the most hard-nosed cynics thought it inconceivable that it could be Walt—that might make the show impossible to take, they said. But, of course, it did nothing of the sort. Once the truth came out, and Brock recovered, I read posts insisting that Walt was so discerning, so careful with the dosage, that Brock could never have died. The audience has been trained by cable television to react this way: to hate the nagging wives, the dumb civilians, who might sour the fun of masculine adventure. “Breaking Bad” increases that cognitive dissonance, turning some viewers into not merely fans but enablers. (83)

Nussbaum’s judgy feminist blinders preclude any recognition of Skyler’s complicity and overweening hypocrisy. And she leaves out some pretty glaring details to bolster her case against Walt—most notably, that before we learn that it was Walt who poisoned Brock, we find out that the poison used was not the invariably lethal ricin Jesse thought it was, but the far less deadly Lily of the Valley. Nussbaum strains to account for the show’s continuing appeal—its fascination—now that, by her accounting, Walt is beyond redemption. She suggests the diminishing screen time he gets as the show focuses on other characters is what saves it, even though the show has followed multiple plotlines from the beginning. (In an earlier blog post, she posits a “craving in every ‘good’ man for a secret life” as part of the basis for the show’s appeal—reading that, I experienced a pang of sympathy for her significant other.) What she doesn’t understand or can’t admit, placing herself contemptuously above the big bad male lead and his trashy, cable-addled fans, trying to watch the show after the same snobbish fashion as many superciliously insecure people watch Jerry Springer or Cops, is that the cognitive dissonance she refers to is precisely what makes the show the best among all the other great shows in the current golden age lineup.

No one watching the show would argue that poisoning a child is the right thing to do—but in the circumstances Walt finds himself in, where making a child dangerously sick is the only way he can think of to save himself, his brother-in-law, Jesse, and the rest of his family, well, Nussbaum’s condemnation starts to look pretty glib. Gus even gave Walt the option of saving his family by simply not interfering with the hit he put on Hank—but Walt never even considered it. This isn’t to say that Walt isn’t now or won’t ever become a true bad guy, as the justifications and cognitive dissonance—along with his aggravated pride—keep ratcheting him toward greater horrors, but then so might we all.

The show’s irresistible appeal comes from how seamlessly it weaves a dream spell over us that has us following right alongside Walt as he makes all these impossible decisions, stepping with him right off the map of the known world. The feeling can only be described as sublime, as if individual human concerns, even the most immensely important of them like human morality, are far too meager as ordering principles to offer any guidance or provide anything like an adequate understanding of the enormity of existence. When we return from this state of sublimity, if we have the luxury of returning, we experience the paradoxical realization that all our human concerns—morality, the sacrosanct innocence of children, the love of family—are all the more precious for being so pathetically meager.

I suspect no matter how bad Walter’s arrogance gets, how high his hubris soars, or how horribly he behaves, most viewers—even those like Nussbaum who can’t admit it—will still long for his redemption. Some of the most intensely gratifying scenes in the series (I’d be embarrassed if anyone saw how overjoyed I got at certain points watching this TV show) are the ones that have Walt suddenly realizing what the right thing to do is and overcoming his own cautious egotism to do it. But a much more interesting question than when, if ever, it will be time to turn against Walt is whether he can rightly be said to be the show’s moral center—or whether and when he ceded that role to Jesse.

If Walt really is ultimately to be lost to the heart of darkness, Jesse will be the one who plays Marlow to his Kurtz. Though the only explicit allusion is Hank’s brief mention of Apocalypse Now, there is at least one interesting and specific parallel between the two stories. Kurtz, it is suggested, was corrupted not just by the wealth he accumulated by raiding native villages and stealing ivory; it was also the ease with which he got his native acolytes to worship him. He succumbed to the temptation of “getting himself adored,” as Marlow sneers. Kurtz had written a report for the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs, and Marlow explains,

The opening paragraph, however, in the light of later information, strikes me now as ominous. He began with the argument that whites, from the point of development we had arrived at, “must necessarily appear to them [savages] in the nature of supernatural beings—we approach them with the might as of a deity.”

What Marlowe discovers is that Kurtz did in fact take on the mantle of a deity after being abandoned to the jungle for too long,

until his nerves went wrong, and caused him to preside at certain midnight dances ending with unspeakable rites, which—as far as I reluctantly gathered from what I heard at various times—were offered up to him—do you understand?—to Mr. Kurtz himself.

The source of Walter White’s power is not his origins in a more advanced civilization but his superior knowledge of chemistry. No one else can make meth as pure as Walt’s. He even uses chemistry to build the weapons he uses to prevail over all the drug dealers he encounters as he moves up the ranks over the seasons.

Jesse has his moments of triumph too, but so far he’s always been much more grounded than Walt. It’s easy to imagine a plotline that has Jesse being the one who finally realizes that Walt “has to go,” the verdict he renders for anyone who imperils children. Allowing for some (major) dialectal adjustments, it’s even possible to imagine Jesse confronting his former partner after he’s made it to the top of a criminal empire, and his thinking along lines similar to Marlow’s when he finally catches up to Kurtz:

I had to deal with a being to whom I could not appeal in the name of anything high or low. I had, even like the niggers, to invoke him—himself—his own exalted and incredible degradation. There was nothing either above or below him, and I knew it. He had kicked himself loose of the earth. Confound the man! he had kicked the very earth to pieces. He was alone, and I before him did not know whether I stood on the ground or floated in the air… But his soul was mad. Being alone in the wilderness, it had looked within itself, and, by heavens! I tell you, it had gone mad.

Kurtz dies whispering, “The horror, the horror,” as if reflecting in his final moments on all the violence and bloodshed he’d caused—or as if making his final pronouncement about the nature of the world he’s departing. Living amid such horrors, though, our only recourse, these glimpses into sublime enormities help us realize, is to more fully embrace our humanity. We can never comfortably dismiss these stories of men who become monsters as mere cautionary tales. That would be too simple. They gesture toward something much more frightening and much more important than that. Humbert Humbert hints as much in the closing of Lolita.

This then is my story. I have reread it. It has bits of marrow sticking to it, and blood, and beautiful bright-green flies. At this or that twist of it I feel my slippery self eluding me, gliding into deeper and darker waters than I care to probe. (308)

But he did probe those forbidden waters. And we’re all better for it. Both Kurtz and Humbert are doomed from the first page of their respective stories. But I seriously doubt I’m alone in holding out hope that when Walter White finds himself edging up to the abyss, Jesse, or Walter Jr., or someone else is there to pull him back—and Skyler isn’t there to push him over. Though I may forget to breathe I won’t hold my breath.

Also read

And

LAB FLIES: JOSHUA GREENE’S MORAL TRIBES AND THE CONTAMINATION OF WALTER WHITE

Also a propos is

And

SYMPATHIZING WITH PSYCHOS: WHY WE WANT TO SEE ALEX ESCAPE HIS FATE AS A CLOCKWORK ORANGE