Percy Fawcett’s 2 Lost Cities

In his surprisingly profound, insanely fun book The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon, David Grann writes about his visit to a store catering to outdoorspeople in preparation for his trip to research, and to some degree retrace, the last expedition of renowned explorer Percy Fawcett. Grann, a consummate New Yorker, confesses he’s not at all the outdoors type, but once he’s on the trail of a story he does manifest a certain few traits in common with adventurers like Fawcett. Wandering around the store after having been immersed in the storied history of the Royal Geographical Society, Grann observes,

Racks held magazines like Hooked on the Outdoors and Backpacker: The Outdoors at Your Doorstep, which had articles titled “Survive a Bear Attack!” and “America’s Last Wild Places: 31 Ways to Find Solitude, Adventure—and Yourself.” Wherever I turned, there were customers, or “gear heads.” It was as if the fewer opportunities for genuine exploration, the greater the means were for anyone to attempt it, and the more baroque the ways—bungee cording, snowboarding—that people found to replicate the sensation. Exploration, however, no longer seemed aimed at some outward discovery; rather, it was directed inward, to what guidebooks and brochures called “camping and wilderness therapy” and “personal growth through adventure.” (76)

Why do people feel such a powerful attraction to wilderness? And has there really been a shift from outward to inward discovery at the heart of our longings to step away from the paved roads and noisy bustle of civilization? As the element of the extreme makes clear, part of the pull comes from the thrill of facing dangers of one sort or another. But can people really be wired in such a way that many of them are willing to risk dying for the sake of a brief moment of accelerated heart-rate and a story they can lovingly exaggerate into their old age?

The catalogue of dangers Fawcett and his companions routinely encountered in the Amazon is difficult to read about without experiencing a viscerally unsettling glimmer of the sensations associated with each affliction. The biologist James Murray, who had accompanied Ernest Shackleton on his mission to Antarctica in 1907, joined Fawcett’s team for one of its journeys into the South American jungle four years later. This much different type of exploration didn’t turn out nearly as well for him. One of Fawcett’s sturdiest companions, Henry Costin, contracted malaria on that particular expedition and became delirious with the fever. “Murray, meanwhile,” Grann writes,

seemed to be literally coming apart. One of his fingers grew inflamed after brushing against a poisonous plant. Then the nail slid off, as if someone had removed it with pliers. Then his right hand developed, as he put it, a “very sick, deep suppurating wound,” which made it “agony” even to pitch his hammock. Then he was stricken with diarrhea. Then he woke up to find what looked like worms in his knee and arm. He peered closer. They were maggots growing inside him. He counted fifty around his elbow alone. “Very painful now and again when they move,” Murray wrote. (135)

The thick clouds of mosquitoes leave every traveler pocked and swollen and nearly all of them get sick sooner or later. On these journeys, according to Fawcett, “the healthy person was regarded as a freak, an exception, extraordinary” (100). This observation was somewhat boastful; Fawcett himself remained blessedly immune to contagion throughout most of his career as an explorer.

Hammocks are required at night to avoid poisonous or pestilence-carrying ants. Pit vipers abound. The men had to sleep with nets draped over them to ward off the incessantly swarming insects. Fawcett and his team even fell prey to even fell prey tovampire bats. “We awoke to find our hammocks saturated with blood,” he wrote, “for any part of our persons touching the mosquito-nets or protruding beyond them were attacked by the loathsome animals” (127). Such wounds, they knew, could spell their doom the next time they waded into the water of the Amazon. “When bathing,” Grann writes, “Fawcett nervously checked his body for boils and cuts. The first time he swam across the river, he said, ‘there was an unpleasant sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach.’ In addition to piranhas, he dreaded candirus and electric eels, or puraques”(91).

Candirus are tiny catfish notorious for squirming their way up human orifices like the urethra, where they remain lodged to parasitize the bloodstream (although this tendency of theirs turns out to be a myth). But piranhas and eels aren’t even the most menacing monsters in the Amazon. As Grann writes,

One day Fawcett spied something along the edge of the sluggish river. At first it looked like a fallen tree, but it began undulating toward the canoes. It was bigger than an electric eel, and when Fawcett’s companions saw it they screamed. Fawcett lifted his rifle and fired at the object until smoke filled the air. When the creature ceased to move, the men pulled a canoe alongside it. It was an anaconda. In his reports to the Royal Geographical Society, Fawcett insisted that it was longer than sixty feet. (92)

This was likely an exaggeration since the record documented length for an anaconda is just under 27 feet, and yet the men considered their mission a scientific one and so would’ve striven for objectivity. Fawcett even unsheathed his knife to slice off a piece of the snake’s flesh for a specimen jar, but as he broke the skin it jolted back to life and made a lunge at the men in the canoe who panicked and pulled desperately at the oars. Fawcett couldn’t convince his men to return for another attempt.

Though Fawcett had always been fascinated by stories of hidden treasures and forgotten civilizations, the ostensible purpose of his first trip into the Amazon Basin was a surveying mission. As an impartial member of the British Royal Geographical Society, he’d been commissioned by the Bolivian and Brazilian governments to map out their borders so they could avoid a land dispute. But over time another purpose began to consume Fawcett. “Inexplicably,” he wrote, “amazingly—I knew I loved that hell. Its fiendish grasp had captured me, and I wanted to see it again” (116). In 1911, the archeologist Hiram Bingham, with the help of local guides, discovered the colossal ruins of Machu Picchu high in the Peruvian Andes. News of the discovery “fired Fawcett’s imagination” (168), according to Grann, and he began cobbling together evidence he’d come across in the form of pottery shards and local folk histories into a theory about a lost civilization deep in the Amazon, in what many believed to be a “counterfeit paradise,” a lush forest that seemed abundantly capable of sustaining intense agriculture but in reality could only support humans who lived in sparsely scattered tribes.

Percy Harrison Fawcett’s character was in many ways an embodiment of some of the most paradoxical currents of his age. A white explorer determined to conquer unmapped regions, he was nonetheless appalled by his fellow Englishmen’s treatment of indigenous peoples in South America. At the time, rubber was for the Amazon what ivory was for the Belgian Congo, oil is today in the Middle East, and diamonds are in many parts of central and western Africa. When the Peruvian Amazon Company, a rubber outfit whose shares were sold on the London Stock Exchange, attempted to enslave Indians for cheap labor, it lead to violent resistance which culminated in widespread torture and massacre.

Sir Roger Casement, a British consul general who conducted an investigation of the PAC’s practices, determined that this one rubber company alone was responsible for the deaths of thirty thousand Indians. Grann writes,

Long before the Casement report became public, in 1912, Fawcett denounced the atrocities in British newspaper editorials and in meetings with government officials. He once called the slave traders “savages” and “scum.” Moreover, he knew that the rubber boom had made his own mission exceedingly more difficult and dangerous. Even previously friendly tribes were now hostile to foreigners. Fawcett was told of one party of eighty men in which “so many of them were killed with poisoned arrows that the rest abandoned the trip and retired”; other travelers were found buried up to their waists and left to be eaten by alive by fire ants, maggots, and bees. (90)

Fawcett, despite the ever looming threat of attack, was equally appalled by many of his fellow explorers’ readiness to resort to shooting at Indians who approached them in a threatening manner. He had much more sympathy for the Indian Protection Service, whose motto was, “Die if you must, but never kill” (163), but he prided himself on being able to come up with clever ways to entice tribesmen to let his teams pass through their territories without violence. Once, when arrows started raining down on his team’s canoes from the banks, he ordered his men not to flee and instead had one of them start playing his accordion while the rest of them sang to the tune—and it actually worked (148).

But Fawcett was no softy. He was notorious for pushing ahead at a breakneck pace and showing nothing but contempt for members of his own team who couldn’t keep up owing to a lack of conditioning or fell behind owing to sickness. James Murray, the veteran of Shackleton’s Antarctic expedition whose flesh had become infested with maggots, experienced Fawcett’s monomania for maintaining progress firsthand. “This calm admission of the willingness to abandon me,” Murray wrote, “was a queer thing to hear from an Englishman, though it did not surprise me, as I had gauged his character long before” (137). Eventually, Fawcett did put his journey on hold to search out a settlement where they might find help for the dying man. When they came across a frontiersman with a mule, they got him to agree to carry Murray out of the jungle, allowing the rest of the team to continue with their expedition. To everyone’s surprise, Murray, after disappearing for a while, turned up alive—and furious. “Murray accused Fawcett of all but trying to murder him,” Grann writes, “and was incensed that Fawcett had insinuated that he was a coward” (139).

The theory of a lost civilization crystalized in the explorer’s mind when he found a document written by a Portuguese bandeirante—soldier of fortune—describing “a large, hidden, and very ancient city… discovered in the year 1753” (180) while rummaging through old records at the National Library of Brazil. As Grann explains,

Fawcett narrowed down the location. He was sure that he had found proof of archaeological remains, including causeways and pottery, scattered throughout the Amazon. He even believed that there was more than a single ancient city—the one the bandeirante described was most likely, given the terrain, near the eastern Brazilian state of Bahia. But Fawcett, consulting archival records and interviewing tribesmen, had calculated that a monumental city, along with possibly even remnants of its population, was in the jungle surrounding the Xingu River in the Brazilian Mato Grasso. In keeping with his secretive nature, he gave the city a cryptic and alluring name, one that, in all his writings and interviews, he never explained. He called it simply Z. (182)

Fawcett was planning a mission for the specific purpose of finding Z when he was called by the Royal Geographical Society to serve in the First World War. The case for Z had been up till that point mostly based on scientific curiosity, though there was naturally a bit of the Indiana Jones dyad—“fortune and glory”—sharpening his already keen interest. Ever since Hernan Cortes marched into the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan in 1519, and Francisco Pizarro conquered Cuzco, the capital of the Inca Empire, fourteen years later, there had been rumors of a city overflowing with gold called El Dorado, literally “the gilded man,” after an account by the sixteenth century chronicler Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo of a king who covered his body every day in gold dust only to wash it away again at night (169-170). It’s impossible to tell how many thousands of men died while searching for that particular lost city.

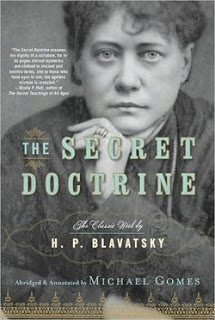

Fawcett, however, when faced with the atrocities of industrial-scale war, began to imbue Z with an altogether different sort of meaning. As a young man, he and his older brother Edmund had been introduced to Buddhism and the occult by a controversial figure named Helena Petrovna Blavatsky. To her followers, she was simply Madame Blavatsky. “For a moment during the late nineteenth century,” Grann writes, “Blavatsky, who claimed to be psychic, seemed on the threshold of founding a lasting religious movement” (46). It was called theosophy—“wisdom of the gods.” “In the past, Fawcett’s interest in the occult had been largely an expression of his youthful rebellion and scientific curiosity,” Grann explains, “and had contributed to his willingness to defy the prevailing orthodoxies of his own society and to respect tribal legends and religions.” In the wake of horrors like the Battle of the Somme, though, he started taking otherworldly concerns much more seriously. According to Grann, at this point,

his approach was untethered from his rigorous RGS training and acute powers of observation. He imbibed Madame Blavatsky’s most outlandish teachings about Hyperboreans and astral bodies and Lords of the Dark Face and keys to unlocking the universe—the Other World seemingly more tantalizing than the present one. (190)

It was even rumored that Fawcett was basing some of his battlefield tactics on his use of a Ouija board.

Brian Fawcett, Percy’s son and compiler of his diaries and letters into the popular volume Expedition Fawcett, began considering the implications of his father’s shift away from science years after he and Brian’s older brother Jack had failed to return from Fawcett’s last mission in search of Z. Grann writes,

Brian started questioning some of the strange papers that he had found among his father’s collection, and never divulged. Originally, Fawcett had described Z in strictly scientific terms and with caution: “I do not assume that ‘The City’ is either large or rich.” But by 1924 Fawcett had filled his papers with reams of delirious writings about the end of the world and about a mystical Atlantean kingdom, which resembled the Garden of Eden. Z was transformed into “the cradle of all civilizations” and the center of one of Blavatsky’s “White Lodges,” where a group of higher spiritual beings help to direct the fate of the universe. Fawcett hoped to discover a White Lodge that had been there since “the time of Atlantis,” and to attain transcendence. Brian wrote in his diary, “Was Daddy’s whole conception of ‘Z,’ a spiritual objective, and the manner of reaching it a religious allegory?” (299)

Grann suggests that the success of Blavatsky and others like her was a response to the growing influence of science and industrialization. “The rise of science in the nineteenth century had had a paradoxical effect,” he writes:

while it undermined faith in Christianity and the literal word of the Bible, it also created an enormous void for someone to explain the mysteries of the universe that lay beyond microbes and evolution and capitalist greed… The new powers of science to harness invisible forces often made these beliefs seem more credible, not less. If phonographs could capture human voices, and if telegraphs could send messages from one continent to the other, then couldn’t science eventually peel back the Other World? (47)

Even Arthur Conan Doyle, who was a close friend of Fawcett and whose book The Lost World was inspired by Fawcett’s accounts of his expeditions in the Amazon, was an ardent supporter of investigations into the occult. Grann quotes him as saying, “I suppose I am Sherlock Holmes, if anybody is, and I say that the case for spiritualism is absolutely proved” (48).

But pseudoscience—equal parts fraud and self-delusion—was at least a century old by the time H.P. Blavatsky began peddling it, and, tragically, ominously, it’s alive and well today. In the 1780s, electro-magnetism was the invisible force whose nature was being brought to light by science. The German physician Franz Anton Mesmer, from whom we get the term “mesmerize,” took advantage of these discoveries by positing a force called “animal magnetism” that runs through the bodies of all living things. Mesmer spent most of the decade in Paris, and in 1784 King Louis XVI was persuaded to appoint a committee to investigate Mesmer’s claims. One of the committee members, Benjamin Franklin, you’ll recall, knew something about electricity. Mesmer in fact liked to use one of Franklin’s own inventions, the glass harmonica (not that type of harmonica), as a prop for his dramatic demonstrations. The chemist and pioneer of science Antoine Lavoisier was the lead investigator though. (Ten years after serving on the committee, Lavoisier would fall victim to the invention of yet another member, Dr. Guillotine.)

Mesmer claimed that illnesses were caused by blockages in the flow of animal magnetism through the body, and he carried around a stack of printed testimonials on the effectiveness of his cures. If the idea of energy blockage as the cause of sickness sounds familiar to you, so too will Mesmer’s methods for unblocking them. He, or one of his “adepts,” would establish some kind of physical contact so they could find the body’s magnetic poles. It usually involved prolonged eye contact and would eventually lead to a “crisis,” which meant the subject would fall back and begin to shake all over until she (they were predominantly women) lost consciousness. If you’ve seen scenes of faith healers in action, you have the general idea. After undergoing several exposures to this magnetic treatment culminating in crisis, the suffering would supposedly abate and the mesmerist would chalk up another cure. Tellingly, when Mesmer caught wind of some of the experimental methods the committee planned to use he refused to participate. But then a man named Charles Deslon, one of Mesmer’s chief disciples, stepped up.

The list of ways Lavoisier devised to test the effectiveness of Deslon’s ministrations is long and amusing. At one point, he blindfolded a woman Deslon had treated before, telling her she was being magnetized right then and there, even though Deslon wasn’t even in the room. The suggestion alone was nonetheless sufficient to induce a classic crisis. In another experiment, the men replaced a door in Franklin’s house with a paper partition and had a seamstress who was supposed to be especially sensitive to magnetic effects sit in a chair with its back against the paper. For half an hour, an adept on the other side of the partition attempted to magnetize her through the paper, but all the while she just kept chatting amiably with the gentlemen in the room. When the adept finally revealed himself, though, he was able to induce a crisis in her immediately. The ideas of animal magnetism and magnetic cures were declared a total sham.

Lafayette, who brought French reinforcements to the Americans in the early 1780s, hadn’t heard about the debunking and tried to introduce the practice of mesmerism to the newly born country. But another prominent student of the Enlightenment, Thomas Jefferson, would have none of it.

Madame Blavatsky was cagey enough never to allow the supernatural abilities she claimed to have be put to the test. But around the same time Fawcett was exploring the Amazon another of Conan Doyle’s close friends, the magician and escape artist Harry Houdini, was busy conducting explorations of his own into the realm of spirits. They began in 1913 when Houdini’s mother died and, grief-stricken, he turned to mediums in an effort to reconnect with her. What happened instead was that, one after another, he caught out every medium in some type of trickery and found he was able to explain the deceptions behind all the supposedly supernatural occurrences of the séances he attended. Seeing the spiritualists as fraudsters exploiting the pain of their marks, Houdini became enraged. He ended up attending hundreds of séances, usually disguised as an old lady, and as soon as he caught the medium performing some type of trickery he would stand up, remove the disguise, and proclaim, “I am Houdini, and you are a fraud.”

Houdini went on to write an exposé, A Magician among the Spirits, and he liked to incorporate common elements of séances into his stage shows to demonstrate how easy they were for a good magician to recreate. In 1922, two years before Fawcett disappeared with his son Jack while searching for Z, Scientific American Magazine asked Houdini to serve on a committee to further investigate the claims of spiritualists. The magazine even offered a cash prize to anyone who could meet some basic standards of evidence to establish the validity of their claims. The prize went unclaimed. After Houdini declared one of Conan Doyle's favorite mediums a fraud, the two men had a bitter falling out, the latter declaring the prior an enemy of his cause. (Conan Doyle was convinced Houdini himself must've had supernatural powers and was inadvertently using them to sabotage the mediums.) The James Randi Educational Foundation, whose founder also began as a magician but then became an investigator of paranormal claims, currently offers a considerably larger cash prize (a million dollars) to anyone who can pass some well-designed test and prove they have psychic powers. To date, a thousand applicants have tried to win the prize, but none have made it through preliminary testing.

So Percy Fawcett was searching, it seems, for two very different cities; one was based on evidence of a pre-Columbian society and the other was a product of his spiritual longing. Grann writes about a businessman who insists Fawcett disappeared because he actually reached this second version of Z, where he transformed into some kind of pure energy, just as James Redfield suggests happened to the entire Mayan civilization in his New Age novel The Celestine Prophecy. Apparently, you can take pilgrimages to a cave where Fawcett found this portal to the Other World. The website titled “The Great Web of Percy Harrison Fawcett” enjoins visitors: “Follow your destiny to Ibez where Colonel Fawcett lives an everlasting life.”

Today’s spiritualists and pseudoscientists rely more heavily on deliberately distorted and woefully dishonest references to quantum physics than they do on magnetism. But the differences are only superficial. The fundamental shift that occurred with the advent of science was that ideas could now be divided—some with more certainty than others—into two categories: those supported by sound methods and a steadfast devotion to following the evidence wherever it leads and those that emerge more from vague intuitions and wishful thinking. No sooner had science begun to resemble what it is today than people started trying to smuggle their favorite superstitions across the divide.

Not much separates New Age thinking from spiritualism—or either of them from long-established religion. They all speak to universal and timeless human desires. Following the evidence wherever it leads often means having to reconcile yourself to hard truths. As Carl Sagan writes in his indispensable paean to scientific thinking, Demon-Haunted World,

Pseudoscience speaks to powerful emotional needs that science often leaves unfulfilled. It caters to fantasies about personal powers we lack and long for… In some of its manifestations, it offers satisfaction for spiritual hungers, cures for disease, promises that death is not the end. It reassures us of our cosmic centrality and importance… At the heart of some pseudoscience (and some religion also, New Age and Old) is the idea that wishing makes it so. How satisfying it would be, as in folklore and children’s stories, to fulfill our heart’s desire just by wishing. How seductive this notion is, especially when compared with the hard work and good luck usually required to achieve our hopes. (14)

As the website for one of the most recent New Age sensations, The Secret, explains, “The Secret teaches us that we create our lives with every thought every minute of every day.” (It might be fun to compare The Secret to Madame Blavatsky’s magnum opus The Secret Doctrine—but not my kind of fun.)

That spiritualism and pseudoscience satisfy emotional longings raises the question: what’s the harm in entertaining them? Isn’t it a little cruel for skeptics like Lavoisier, Houdini, and Randi to go around taking the wrecking ball to people’s beliefs, which they presumably depend on for consolation, meaning, and hope? Indeed, the wildfire of credulity, charlatanry, and consumerist epistemology—whereby you’re encouraged to believe whatever makes you look and feel the best—is no justification for hostility toward believers. The hucksters, self-deluded or otherwise, who profit from promulgating nonsense do however deserve, in my opinion, to be very publicly humiliated. Sagan points out too that when we simply keep quiet in response to other people making proclamations we know to be absurd, “we abet a general climate in which skepticism is considered impolite, science tiresome, and rigorous thinking somehow stuffy and inappropriate” (298). In such a climate,

Spurious accounts that snare the gullible are readily available. Skeptical treatments are much harder to find. Skepticism does not sell well. A bright and curious person who relies entirely on popular culture to be informed about something like Atlantis is hundreds or thousands of times more likely to come upon a fable treated uncritically than a sober and balanced assessment. (5)

Consumerist epistemology is also the reason why creationism and climate change denialism are immune from refutation—and is likely responsible for the difficulty we face in trying to bridge the political divide. No one can decide what should constitute evidence when everyone is following some inner intuitive light to the truth. On a more personal scale, you forfeit any chance you have at genuine discovery—either outward or inward—when you drastically lower the bar for acceptable truths to make sure all the things you really want to be true can easily clear it.

On the other hand, there are also plenty of people out there given to rolling their eyes anytime they’re informed of strangers’ astrological signs moments after meeting them (the last woman I met is a Libra). It’s not just skeptics and trained scientists who sense something flimsy and immature in the characters of New Agers and the trippy hippies. That’s probably why people are so eager to take on burdens and experience hardship in the name of their beliefs. That’s probably at least part of the reason too why people risk their lives exploring jungles and wildernesses. If a dude in a tie-dye shirt says he discovered some secret, sacred truth while tripping on acid, you’re not going to take him anywhere near as seriously as you do people like Joseph Conrad, who journeyed into the heart of darkness, or Percy Fawcett, who braved the deadly Amazon in search of ancient wisdom.

The story of the Fawcett mission undertaken in the name of exploration and scientific progress actually has a happy ending—one you don’t have to be a crackpot or a dupe to appreciate. Fawcett himself may not have had the benefit of modern imaging and surveying tools, but he was also probably too distracted by fantasies of White Lodges to see much of the evidence at his feet. David Grann made a final stop on his own Amazon journey to seek out the Kuikuro Indians and the archeologist who was staying with them, Michael Heckenberger. Grann writes,

Altogether, he had uncovered twenty pre-Columbian settlements in the Xingu, which had been occupied roughly between A.D. 800 and A.D. 1600. The settlements were about two to three miles apart and were connected by roads. More astounding, the plazas were laid out along cardinal points, from east to west, and the roads were positioned at the same geometric angles. (Fawcett said that Indians had told him legends that described “many streets set at right angles to one another.”) (313)

These were the types of settlements Fawcett had discovered real evidence for. They probably wouldn’t have been of much interest to spiritualists, but their importance to the fields of archeology and anthropology are immense. Grann records from his interview:

“Anthropologists,” Heckenberger said, “made the mistake of coming into the Amazon in the twentieth century and seeing only small tribes and saying, ‘Well, that’s all there is.’ The problem is that, by then, many Indian populations had already been wiped out by what was essentially a holocaust from European contact. That’s why the first Europeans in the Amazon described such massive settlements that, later, no one could ever find.” (317)

Carl Sagan describes a “soaring sense of wonder” as a key ingredient to both good science and bad. Pseudoscience triggers our wonder switches with heedless abandon. But every once in a while findings that are backed up with solid evidence are just as satisfying. “For a thousand years,” Heckenberger explains to Grann,

the Xinguanos had maintained artistic and cultural traditions from this highly advanced, highly structured civilization. He said, for instance, that the present-day Kuikuro village was still organized along the east and west cardinal points and its paths were aligned at right angles, though its residents no longer knew why this was the preferred pattern. Heckenberger added that he had taken a piece of pottery from the ruins and shown it to a local maker of ceramics. It was so similar to present-day pottery, with its painted exterior and reddish clay, that the potter insisted it had been made recently…. “To tell you the honest-to-God truth, I don’t think there is anywhere in the world where there isn’t written history where the continuity is so clear as right here,” Heckenberger said. (318)

[The PBS series "Secrets of the Dead" devoted a show to Fawcett.]

Also read

And: